"When I was fair and young and favour graced me/ Of many was I sought their mistress for to be/ But I did scorn them all and answered them therefore/ Go, go, go, seek some other where/ Importune me no more."

"When I was fair and young and favour graced me/ Of many was I sought their mistress for to be/ But I did scorn them all and answered them therefore/ Go, go, go, seek some other where/ Importune me no more." -- Elizabeth I.

Taking power as a 25 year-old and reigning for 45 years, Elizabeth was the star at the center of the 16th century English universe, which produced the foundations of the British Empire, lasting British Protestantism,

Shakespeare and the beginnings of the English Renaissance. She was not only popular with the English people, but a shrewd judge of political talent, a careful diplomat and a poet whose military dispatches were even beautifully written.

She was born on this day in 1533 in Greenwich. Before she was 3, the head of her mother, Anne Boleyn, had been ordered off her mother's shoulders by her father, Henry VIII, and within 2 years, she was declared to be an illegitimate child when her father remarried to Jane Seymour, the mother of Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI. Elizabeth nonetheless received a first-rate education, and being trained as a Protestant was encouraged to repudiate traditional authority and seek her own conclusions.

Henry VIII designated Elizabeth as third in line for the throne, behind Edward and her half-sister Mary, which catapulted her to superstar status. With ivory skin, auburn hair and delicate hands, she became the object of feverish courtship by power-hungry nobles -- in particular, Thomas Seymour, a handsome, ambitious cad who, though married to Catherine Parr, engaged in chasing Elizabeth around her house, slapping and tickling her whenever he could; his plots against the throne eventually resulted in his execution, however, and some credit his execution with hardening Elizabeth's amorousness for the rest of her life.

After the death of Edward VI and the brief attempt to install Lady Jane Grey on the throne, Elizabeth was proposed as a Protestant alternative to her staunchly Catholic half-sister Mary as Queen, but Elizabeth wisely pleaded illness and declined the invitation. While Mary reigned, Elizabeth quietly waited, initially banished to the Tower of London as a traitor, surviving Mary's murderous jealousy with intelligence, patience and courage.

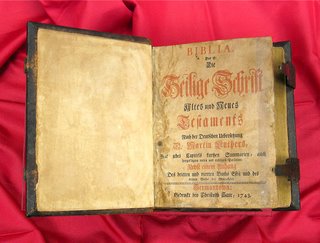

Upon Mary's death, on November 17, 1558, Elizabeth was crowned Queen at Westminster. Although the dying Mary had urged Elizabeth to keep England Catholic, Elizabeth knew that England had become irreversibly Protestant, Mary's campaign of terror against heretics notwithstanding, and Elizabeth followed her own moderate, pragmatic conscience by establishing the Church of England as the State Church, with herself as "governor." When the citizens of Oxford asked her how they should bury the bones of disinterred Catholic saints and recently burned Protestant martyrs, her reply was similarly practical: "Mix them," she is said to have advised.

Beyond England's religious difficulties, the nation was impoverished when she took the throne, and was ripe for the taking by either France or Spain. European observers all expected Elizabeth to marry and settle the question of England's alliances, but Elizabeth became adept at using potential suitors as diplomatic and political pawns while she girded England for the coming storm. Married to the throne instead, she chose extraordinarily talented advisers, such as William Cecil, for many years her chief advisor; Francis Walsingham, her security chief who protected her from the many murder plots which erupted in her day; and Walter Raleigh, her Lord Chancellor. She never let any of them rise too high, however -- not even her favorite, the less talented but handsome Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester -- and ruled alertly as a fearsome autocrat.

In 1570, Pope Pius V attempted to speed up the European conquest of England by excommunicating Elizabeth from the Catholic church, thus freeing English Catholics to defy her authority and fight against her alongside the Catholic monarchs of Europe; but Elizabeth's policy of toleration resulted in a united England, and no revolt followed. It wasn't until 1588, when it was clear that Elizabeth would not marry and all other incursions had failed to weaken Elizabeth's power, that Philip II of Spain sent his Spanish Armada of ships to the coast off Cornwall. Her chief sea-dog Francis Drake directed the use of fire-ships against the Spanish fleet as it rested near Calais, panicking the Spanish and sending them North toward bad weather and English defeat.

Her attention then turned to colonization in the Western hemisphere, where the Spaniards had previously reaped so much gold. At 51, she became infatuated with the young Earl of Essex, and her indulgence almost cost her the throne when Essex led a rebellion against her in 1601; he was executed for his antics. Elizabeth died not long afterward, grudgingly (as she preferred not to speak of her own death or questions of succession) naming James I as her successor.

Being a central figure in the development of Anglo-American culture, she has been portrayed on film often, memorably by Sarah Bernhardt (

The Loves of Queen Elizabeth, 1912),

Bette Davis (twice, in

The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex, 1939, and

The Virgin Queen, 1955), Glenda Jackson (twice, on TV in

Mary Queen of Scots and

Elizabeth R, both 1971), Judi Dench (

Shakespeare in Love, 1998), Cate Blanchett (

Elizabeth, 1998) and Helen Mirren (on TV, in

Elizabeth I, 2005). For a good laugh, try either Miranda Richardson in

Blackadder II (TV, 1985) or Quentin Crisp in

Orlando (1992).

Labels: Kings and Queens