Running the Table

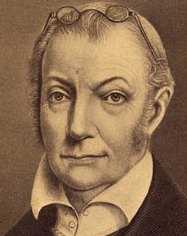

You know him as Aaron Burr, traitor and murderer, and he was born on this day in 1756 in Newark, New Jersey.

His chief enemies in his time were a singular pair of founding fathers standing at opposite ends of the political spectrum: Thomas Jefferson, the visionary of the Democratic-Republicans, and Alexander Hamilton, the visionary of the Federalists. Jefferson and Hamilton were themselves enemies of each other, thereby disproving in Burr's case the old adage that the "enemy of my enemy is my friend." But Jefferson and Hamilton, though both flawed individuals, have been canonized in American history -- heck, they both appear on the U.S. currency -- whereas Burr has been dressed up and served as the villain of the early Republic, despite his largely forgotten profile as a Revolutionary War hero, a leading Manhattan advocate, a legislator who proposed the abolition of slavery and a national leader admired by at least some New York partisans, John Jay among them.

Both Jefferson and Hamilton were as determinedly self-interested as Burr, but they were ideologues; Burr was a dispassionate moderate, and perhaps because he lacked strong ideological convictions, he appeared to have been the most self-interested. At any rate, God help the moderate who raises the ire of partisans on both margins.

The son of Princeton's 2nd president and grandson of revivalist preacher Jonathan Edwards, Burr switched from studying theology to law, but interrupted his education to join the American revolution. In the Continental Army he rose quickly, caught Washington's eye as a capable if squally leader, and he proved himself in battle in Quebec and at Monmouth. Washington accepted his resignation in 1779, whereupon Burr entered the New York Bar and quickly established himself as a leading competitor of Hamilton. He entered the state assembly in 1784 as a protégé of Governor George Clinton, a Hamilton foe, who secured Burr's election to U.S. Senate over Hamilton's father-in-law Philip Schuyler in 1791.

Recognizing the importance of New York's electoral votes, the Democratic-Republicans nominated Burr as Jefferson's running mate for Jefferson's losing bid in the 1796 presidential election. Although Burr lost re-election to the Senate the following year, he had built a strong coalition of state Republicans around him; in 1800 he won election to the state senate, and his group of "Burrites" controlled the state legislature. From that vantage point, he engineered his selection as Jefferson's running mate again that year and delivered New York's electoral votes as the Republicans beat the Federalists.

However, under the "two ballot" electoral system of the time, Jefferson and Burr individually tied for the most presidential votes. Burr publicly asserted that he would not contest Jefferson's election, but Federalist machinations prevented a break in the congressional deadlock between the two until Hamilton, fearing Burr would exercise too much influence in his home state as president, held his nose and engineered the victory of Jefferson.

Jefferson, however, didn't trust Burr or his centrist views, so Burr effectively became an exile within the administration and his own party. Lashing out and trying to play the angles, Burr published a private letter by Hamilton denouncing the character of his fellow Federalist, former president John Adams, to make Hamilton look silly, and Hamilton's friends countered by claiming that Burr had tried to steal the election from Jefferson. Already abandoned by Jefferson, Burr resigned from the Republican Party and ran for governor of New York against the Republican candidate in 1804. Although some non-Hamiltonian Federalists offered to back him if he would align himself with a New England plan to secede from Jefferson's union, Burr declined to join the cabal; they backed him nonetheless, though, while Hamilton clucked and hissed, and Burr lost.

His career now in steep decline, Burr lashed out at Hamilton again -- like an ex-heavyweight champ challenging another ex-heavyweight champ to settle old scores and set the stage for a comeback -- and called Hamilton to a duel in June 1804 over Hamilton's undermining behavior during the campaign for governor. Hamilton, also a man whose career was in decline, felt he had no choice but to accept. On June 11, 1804, Burr met Hamilton at Weehawken, New Jersey, and in the early morning mist Burr dealt Hamilton a mortal gunshot wound.

With warrants out for his arrest Burr fled South and came to a realization: abandoned by the Republicans and despised by the Federalists, any chance he had to regain influence would require him to run the table, so to speak. He solicited help from a few wealthy friends, including U.S. Army general James Wilkinson (who was secretly a Spanish double agent!), and began to hatch a scheme to start a new nation from among the crumbling Spanish territories in the West. After a trip down the Mississippi in April 1805, he became convinced the plan would not work without support from the Spanish, so he pursued diplomatic channels to get it. They would not buy in, but they did give him $10,000 to help defend the Spanish against U.S. incursions in the South.

Burr returned to the Mississippi in the summer of 1806, but Wilkinson, fearing his cover would be blown, tipped off Jefferson, who ordered his arrest; Jefferson himself feared that a person with Burr's capabilities could indeed revitalize the Spanish occupation of North America and challenge his own continental visions.

Jefferson's Virginia rival, Chief Justice John Marshall, presided at Burr's trial for treason, and it was Marshall's strict definition of "treason" that ultimately led to Burr's acquittal. His reputation irretrievably ravaged, however, Burr moved to Europe for a time, attempted to get France or England interested in his plans, and finally returned to his practice in Manhattan in 1812. He married a wealthy widow 20 years his junior in 1833, squandered her fortune, and died on the day her divorce from him was granted, at the age of 80.

Categories: American-Politicians, Presidential-Campaigns

4 Comments:

Some say Hamilton fired first in the duel chosing to go high and right of Burr. Burr on the other hand fired to kill.

Any truth in that view of the duel or is it some yarn generated by followers of Hamilton?

Your chronology is accurate -- Hamilton apparently fired first; Burr remained standing, then fired. Although various partisans would claim that Hamilton meant to hit Burr but missed, or that Hamilton aimed high on purpose to avoid hitting Burr -- it's pretty much impossible at this point to figure out what was on Hamilton's mind and what was on Burr's mind at the instant of the confrontation. With more certainty, we can say that Burr regretted the incident, and that the incident certainly illustrated the futility of dueling as a means for settling political disputes in the Early Republic.

Not that this stopped Andrew Jackson from engaging in duels, repeatedly and with relish . . .

Of course in modern times, a certain southern senator challenged MSNBC's Chris Matthews to a duel in New York City! Or the senator at least wished on national television that he and Matthews could settle their policital dispute on the field of honor.

In yesteryear, we had duels. Now we have anger management.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home