Gutenberg

"Artists, sailors, children -- and inventors. Lord, protect your most innocent sheep!" -- Felix Blueblazes.

It is hard to imagine what the last 550 years would have been like without the mountains of printed babel (not unlike what you're reading now, only on paper) which have accumulated as a consequence of Johannes Gutenberg's innovations: individual metal stamp-molded type letters, easily mass produced and reusable, combined with a pressing machine like one previously used principally for squashing grapes, the metal letters painted with an oil-based ink and pushed onto paper to create multiple copies of a page of text which would have taken a scribe several days and a wrist-splint to have created by hand.

Impossible, in fact. Gutenberg's invention is likely the single most widely influential creation in a 1,000 years of workshop tinkering. Suddenly, for the first time since the invention of writing, "the word" was available in mass quantities. It could be shouted (and more importantly, repeated) out from between stiff leather covers, down highways and trade routes. For the poet, more editions offered more chances at immortality; for the scientist, the cost of research was reduced dramatically as formulas and ideas could be exchanged quickly, relatively cheaply and with a guaranteed uniformity; and for the entrepreneur, the press meant greater saturation of the marketplace with handbills and sales circulars. Even the church, initially unnerved by the ease with which any heretic could publish his blasphemies, found a use for Gutenberg's contraption.

The "entrepreneur" is not the central character in Gutenberg's story, however, for the story of Gutenberg and his press is not about the lone innovator who forged a media empire, but another one about how the money guys used their muscle to squeeze the idea-man out of the fruits of his dreams and sweat. (What did you expect? Whoever said Hearst or Murdoch ever invented anything?)

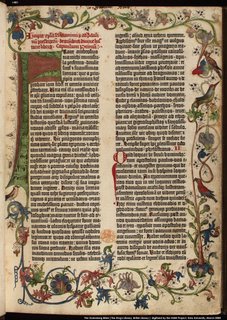

Almost everything we know about Gutenberg comes from litigation records. Trained as a metallurgist, Gutenberg earned his living making and selling tourist trinkets to pilgrims in Strasbourg. He noticed, however, that the hottest item going among pilgrims were "indulgences," elaborately hand-illuminated pieces of parchment which were a kind of medieval Roman Catholic "get-out-of-hell free" card, sold by the church to the fretful faithful -- much to the horror of later reformers such as Martin Luther. Manual painting of these indulgences took time; woodblock printing, occasionally used for illustrations, was time-consuming and impractical for text. In his workshop during the 1430s, Gutenberg secretly toiled away at a method and apparatus which would allow for the inexpensive mass production of indulgences; but as he toiled, Gutenberg realized the greater import of his project and began to work on a printed Bible and a Psalter -- to be mass-produced, but at the same time to incorporate the artistry of the illuminated manuscript.

In October 1448, he persuaded a wealthy financier, Johann Fust, to loan him completion funds. Like all venture capitalists, Fust was looking for a quick return on his investment, and like all inventors, Gutenberg was interested in perfection; and like many venture capital deals, Gutenberg and Fust ended up in court. At about the time of their completion, Fust gained control of Gutenberg's beautiful Bible and two-colored Psalter, as well as all of the instruments of their creation (except for Gutenberg himself). True, Gutenberg hadn't paid back the 2,026 guilders plus interest -- but he had stood on the precipice of his putative fortune, only to have it and his life's work taken away from him. Fust and his new partner published the Gutenberg Bible in 1456.

As Fust and a hundred imitators launched the Gutenberg Age, a patron in Mainz took pity on Gutenberg and gave him some printing tools with which to tinker, but there is no evidence that it ever amounted to much. Blind and frail at the end of his life, Gutenberg was named a ward of the local government and given a yearly allowance of cloth, grain and wine. He is thought to have died on this date in 1468 in Mainz, Germany at the age of 74 or so.

Labels: Books, Business and Finance

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home