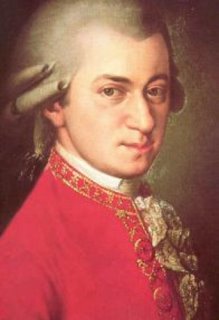

Mozart

At age 3, he was playing the keyboard; at 5, he was composing music; and at 6, his father Leopold, music director to Archbishop Sigismund von Schrattenbach of Salzburg and a well-known violin teacher, took little Wolfgang Theophilus ("Amadeus") Mozart and his sister Anna Maria on a grueling tour to display their talents to the crowned heads of Europe.

He was hailed as a master virtuoso, even as he sat in the lap of Empress Maria Theresa and cheekily proposed to her little rug-rat Marie Antoinette. In short, Wolfgang Mozart (born on this day in 1756 in Salzburg) was an 18th century child star who grew up with a child star's typical lack of a fully-formed perspective on real life. Did this lack of perspective cripple his creativity and leave him with a pathologically underdeveloped conscience, driving him, like little Alfalfa Switzer or little Dana Plato, to a miserable, pathetic final chapter of the kind that gets played out, gleefully and often, on an episode of E! True Hollywood Story?

Not even close. For one thing, Mozart's life, while cut short by illness, was not a story of poverty and ruin; he was bad with decisions about money, but had paid his debts by the time of his death and seemed poised to enjoy a period of affluence. Secondly, unlike sitcom kids who show up in police reports, whose brittle fame rests upon a relatively unassuming charm which does not age well, Mozart's talent was genuine, deep and ever maturing.

One of the side effects of spending most of his childhood on the road was that Mozart's sponge-like mind absorbed the best of what he had heard, permitting him to create a composition style that was a synthesis of classical forms as they were variously interpreted around Europe. Stylistically, he was no innovator, but rather he wrote in the modes of his friends and mentors Johann Christian Bach (whom Mozart met in London in 1764) and Franz Joseph Haydn, infusing his music with an effortless balance in which every note is essential. His absolute pitch and his ability to remember, note for ever-loving note, long and complex passages of music are legendary; while combing through the Italian classical style in Rome during his teens, he once wrote down the entire score of Allegri's unpublished Miserere after two listenings, leading the astonished Clement XIV to bestow a papal knighthood on him.

While this man-child's days were filled with noisy parties, flowing wine, flirtatious women and fart jokes, music was in both form and substance the entire fabric of his inner life, and it was as easy as breathing for him. It has often been said that while Beethoven labors to show his listeners every drop of sweat in his music, Mozart makes it all sound so simple that one can easily miss how remarkable his creations are. His work habits, well-illustrated in Milos Forman's film Amadeus (1984, based on Peter Shaffer's 1979 play), often involved composing entire pieces in his mind, sometimes while occupying himself with billiards, and waiting for the pressure of a deadline to force him to put pen to paper. When the pressure came, he might sit up all night scribbling out what he had in his head, fine-tuning his fully-formed passages as though improvising at the keyboard, with barely ever a revision.

By the age of 15 he had composed about 100 pieces, helped along by the indulgence of Archbishop von Schrattenbach, who permitted Mozart to go on tour and find other commissions. After von Schrattenbach's death in 1771, however, Mozart found himself attached to a less understanding master, Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo, who didn't think servants ought to have any lives, creative or otherwise, outside of their duties to him. Mozart nevertheless spent as much time away from sleepy Salzburg as he could, settling for a time in Paris, where the 22-year old tried to support himself by teaching and composing. Mozart's restlessness, and his insubordinate attitude, culminated in the firing of both Wolfgang and his father in 1781 (Mozart was actually physically ejected from the archbishop's home) -- just as his first mature stage work, the opera Idomeneo, was opening in Munich to much acclaim.

He moved to Vienna, vowing to be a successful freelance composer and not someone's servant, and fell in with the Weber sisters, some singers he had met in Paris; against his father's wishes, after being turned down by the eldest sister, Wolfgang married Constanze Weber in 1782. At that moment, he was the toast of Vienna (and the envy of his rival composers) for his comic singspiel, The Abduction from the Seraglio, with its voguish Ottoman motif. Thus, he began his Vienna period, his final 9 years, as a newlywed with greater responsibilities and debts, and as the ditty-writing flavor-of-the-month.

His Vienna period, however, would represent an unmatched period of brilliance and creativity. In the months following the Abduction, Mozart would display his unique blend of German technical mastery and veiled Italianate passion in chamber works (such as the Quintet in E-flat for Horn & Strings, 1782; the Quintet in E-flat for Piano & Winds, 1784; and the 6 "Haydn" Quartets, dedicated to his old friend, 1782-5), two of the finest concertos for piano (No. 20 in D, February 1785; and No. 21 in C, March 1785) and symphonies (notably No. 35 in D, the brisk "Haffner," 1782; and No. 36 in C, "Linz," 1783).

Opera, however, paid the bills, and Mozart expressed his desire to write a comic opera based on Beaumarchais' notorious play The Marriage of Figaro. Although Joseph II had banned the play, the Emperor lifted his ban for Mozart's benefit, perhaps at the urging of rivals such as Antonio Salieri who hoped to see him fail. Mozart's new opera (1786, with a libretto by the rakish Lorenzo Da Ponte), full of bright, singable numbers, was a success at its premiere, but it was a tad controversial for its jabs at nobility, and it quickly closed. The fact that Figaro played well in Prague was of little financial comfort to Mozart, until he and Da Ponte received a commission from Prague for another opera, Don Giovanni (1787), a heady mixture of mythological allusion, broad comedy and tragedy which was another rousing success in Prague. In Vienna, however, Joseph II supposedly said that the opera had "too many notes," damning it to another short run.

Even in dire financial straits, however, Mozart's inspiration could not be checked: his most famous melody, the irrepressibly charming Serenade for Strings in G ("Eine kleine nachtmusik") came in the summer of 1787; and during 6 weeks in the summer of 1788, he wrote what would be his last 3 symphonies -- No. 39 in E-flat, No. 40 in G minor, and the transcendent "Jupiter," No. 41 in C -- bringing the "[c]lassical symphonic form to the highest perfection it would ever reach" (Swafford).

His last collaboration with Da Ponte, Cosi fan tutte (1790), a comic opera dressed in earnest music, was their least popular; but Mozart would follow it with what some say was his finest stage piece, The Magic Flute (1791). Composed at the behest of one of his freemason drinking buddies, a pop stage hack and impresario named Emanuel Schikaneder, the libretto was based on a fairy tale that appeared in Christoph Wieland's Dschinnistan. Schikaneder planned a slapstick farce, wrapped around Masonic symbolism and a grinning dose of misogyny; Mozart wrote music for it that transcended Schikaneder's cheesy sketches, creating something noble, beautiful and ultimately inspiring.

Nonetheless, before The Magic Flute premiered, Mozart knew he was gravely ill (perhaps from a kidney disorder), a fact that made the arrival of a mysterious guest who wished to commission a requiem mass all the more foreboding. As it turned out, the visitor was not Salieri (as Forman and Shaffer would have it), but a representative of Count Franz von Walsegg, a musical dilletante who planned to claim the Requiem as his own after Mozart's death. To complete it, Mozart indeed wrote himself to the brink of death, and in the fragment, one can hear that it comes from a man who was facing his own mortality. Dictating from his deathbed, with meddling doctors prescribing irritants, he received the news that The Magic Flute was a crowd-pleaser, and died at the age of 35, leaving the Requiem unfinished. (It was later ably completed by his pupil Franz Sussmayr.)

Contrary to legend, he was not buried in a pauper's grave, though it was an anonymous mass grave, in accordance with Joseph II's contemporary health decrees. His memorial service in Prague was attended by thousands, and few of the musical cognoscenti doubted that the world had lost a genius. For awhile he fell out of favor, muffled by Beethoven's pyrotechnics, but composers always understood Mozart's perfection, and by the 20th century, certainly, Mozart's place of honor within the pantheon of the world's great artists (not just the composers, mind you) was unassailable.

Labels: Classical Music

1 Comments:

Thanks for the wonderful article - I found it through Technorati's Classical Music tag.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home