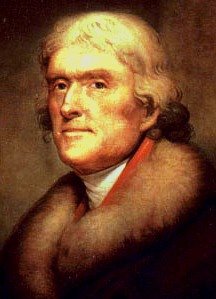

Stone Cold Jefferson

"Doesn't it give you chills?," asks a woman standing inside John Russell Pope's justly praised memorial to Thomas Jefferson on the south side of the Tidal Basin in Washington.

Yes, that about sums it up: we admire Jefferson-the-icon enough to give him a breathtaking monument, but as a man he leaves us a little cold. Sure, there are Jefferson cultists among us, but as much as we Americans adore our innovators, we sometimes rebel against our icy know-it-alls, especially when we get a whiff of their intellectualism; we love our founding fathers, and square-jawed Jefferson is principal among them, but few among us can identify with the kind of nation he wanted to create. We even hold a special place in our hearts for our presidents, but Jefferson himself regarded this status so poorly that he neglected to mention it among his achievements on his self-written epitaph.

Even among today's political philosophers, there is disagreement about the meaning and significance of Jeffersonian thought -- ranging from the depiction of Jefferson as a founder of modern American conservatism (based on his opinion that "that government is best which governs least"), to the idea that he is the father of progressive liberalism (for statements such as "laws and institutions . . . must advance to keep pace with the times" and "a little rebellion now and then . . . is a medicine necessary for the sound health of government"), to the view that Jefferson was at best a woolly-headed dilettante as a theorist without anything resembling a coherent philosophy -- to the bizarre notion, advanced by one lunacritic, that the 20th century leader who best embodied Jeffersonian values was Pol Pot.

Then, of course, there's the story of his sexual relationship with his slave, Sally Hemings, and the slave children he supposedly sired with her after the death of his wife (a charge that recent DNA tests have established to be "highly probable," although this is still a matter of dispute); mix these circumstances with his then-radical assertion that "all men are created equal," his periodic calls for the end to the slave trade, and his simultaneously harsh assessments of the character of African-Americans, and we cannot help but come away with a disturbing sense of his asymmetry as a man, at best -- or of his hypocrisy, at worst.

These paradoxes, his apparent feet of clay, tend to move us here in the 21st century to try to understand him as we do the national politicians of our own time -- flawed giants we hate to love, and love to hate, in whose hands we place our collective fate. It is perhaps best to remember him as a multi-faceted man, in a poetic echo of John Kennedy's famous tribute, that an assembled gathering of Nobel prize winners was "the most extraordinary collection of talent, of human knowledge, that has ever gathered at the White House, with the possible exception of when Thomas Jefferson dined alone."

Born on this day in 1743 in Albemarle County, Virginia, the son of a social climbing Virginia planter, young Thomas Jefferson studied Greek, Latin and French with local parsons until, shortly after the death of his father, at age 17 he enrolled at the College of William and Mary. At 19, he began reading law with George Wythe, and after an extraordinarily long clerkship, entered the Bar at age 24.

After 2 years of law practice (during which he spent a good deal more time focusing on the initial design and construction of Monticello, his neo-Palladian plantation manse, with which he continued to tinker throughout the rest of his life, adding weather devices, clocks, retractable beds and innumerable other features of his own design), he followed in his father's footsteps by getting elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, where he quickly aligned himself with the anti-British faction. In 1774, around the time that he inherited his father-in-law's acreage and 135 slaves, he penned A Summary View of the Rights of British America, drawing upon the ideas of Enlightenment philosophers -- an assiduously well-reasoned argument against control by British Parliament which was intended as a set of instructions for Virginia's first delegates to the Continental Congress; published anonymously, as his authorship came to be known it earned him a minor following as a theoretician of liberty among other anti-British politicians throughout the colonies.

Shortly thereafter, as a member of the Continental Congress, he was the logical choice of a specially charged committee (consisting of Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Sherman and Robert R. Livingston) to draft what would become America's Declaration of Independence; his 1,322-word text (in final form, after some minor wordsmithing by his congressional colleagues, as well as the deletion of his condemnation of the slave trade at the demand of Southern delegates) was, in his own words, an attempt "to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent."

The Declaration made him famous, or rather infamous in some quarters, and he returned to the Virginia legislature with greater political clout during the Revolution, pushing through reforms abolishing primogeniture and establishing religious freedom in Virginia. The war came to Virginia as Jefferson entered the statehouse as Virginia's governor in 1779, a period which would not prove to be Jefferson's finest hour: when the British invaded Richmond in 1781, Jefferson resigned as governor and fled on horseback to Monticello; with the British now in pursuit of Jefferson as one of the foremost of the traitors to the crown, Jefferson and his family fled again, this time to Poplar Forest, near Lynchburg, Virginia (the later site of his neoclassical octagonal retreat, which he completed in 1812), where he remained in seclusion until 1783 -- humiliated and accused by some of cowardice under fire (although an official inquiry later cleared him of the charge).

There he devoted himself to writing Notes on the State of Virginia (published in 1786). Ostensibly a statistical snapshot of the demographics and economic conditions of the state, Jefferson also devoted a large section of the work to natural history, countering the prevalent European view that the flora and fauna of the New World were inferior to those of Europe. Furthermore, throughout the finished product he provided a more comprehensive view of his ideas for political and social reform -- touching upon slavery, native Americans, education, religion and his desire to cultivate and encourage a decentralized, minimally-governed agrarian society, with gentlemen farmers, ample elbow-room and workshop-sized industry, without the plague of a corporate aristocracy; it would be the touchstone of Jeffersonian philosophy, largely written in the detached manner of a man who had given up on his own ambitions to effect change.

With the death of his wife Martha in 1782, however, he cut short his premature retirement and spent another term in the Continental Congress, where he helped to establish the decimal system of American coinage that we use today. He sat out of one fundamental phase of post-Revolutionary America -- the drafting and enactment of the Constitution -- while serving as minister to France (1785-9), although he cast his lot with his colleague James Madison on the scene, ultimately supporting the idea of a strong federal government in exchange for the reservation of the freedoms contained in the Bill of Rights, perhaps in reaction to the excesses he saw in the French Revolution.

Jefferson returned to the newly formed United States to become the first Secretary of State, under President Washington, in 1790, but as his disagreements with Treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton over dealing with Britain and France grew more intense, Jefferson resigned in 1793.

He returned to Monticello, content to farm and tinker, but as Washington looked forward to retirement, Madison began to agitate for Jefferson's election as president, hoping to avoid Vice President Adams' imminent favoring of Britain over France; although Jefferson lost the election in 1796, under the Constitution, as the second highest vote-getter, he was elected vice-president -- a position Jefferson loathed, but nonetheless used as a platform to criticize aspects of Adams' Federalist program, including the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Portrayed as the friend of individual liberty and states' rights, Jefferson beat Adams in the 1800 re-match, and was reelected for a second term as president in 1804. It is surmised that Jefferson's greatest accomplishment as president was his purchase of the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon in 1803, doubling the size of the U.S. for a mere $15 million. In 1806 he dispatched his private secretary Meriwether Lewis and soldier William Clark to explore the territory and provide a comprehensive report on its flora, fauna and ethnography, an executive act still celebrated as the grandest of national gestures to the spirit of discovery, for the benefit of science and knowledge. He also signed into law a bill that abolished the importation of slaves beginning in 1808; but his effectiveness was called into question with the disastrous economic results of his embargo against Britain and France, and when his second term was complete, he was relieved to be retiring to Monticello for the last time, to engage in winemaking and other agricultural and scientific pursuits.

He was, however, deeply in debt due to bad business decisions, and it was not until he sold his 6,500-volume book collection to the Library of Congress (recently gutted when the British burned Washington during the War of 1812) that he was able to recover a comfortable financial footing. His final years were devoted to his establishment of the University of Virginia at Charlottesville (an attempt at fulfilling his vision of an education enabling every citizen "to know his rights" under government), for which he designed the buildings, chose the faculty and served as rector.

As every schoolchild knows, Thomas Jefferson died a few hours before his alternating friend-and-foe John Adams, the other surviving founding father, on July 4, 1826 -- the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence -- a poetically well-ordered conclusion which cannot help but direct our eye back to what is fundamental about Jefferson's message: the unassailable common sense of liberty.

Labels: American Politicians, Architecture, Philosophy, US Presidents

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home