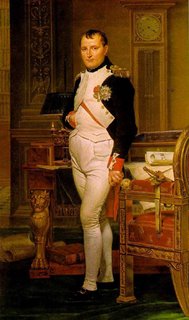

Napoleon

A humorless, raw-tempered, 5'-4" to 5'-6" Corsican who possessed a vulgar twang when ordering his foie gras turned out to be the most influential French commander since Charlemagne, a fact which has left the proud French ambivalent about his memory. He was denied a burial in St. Denis, where the French kings are entombed, but given a dramatically set sarcophagus at the center of Les Invalides in Paris, inside seven nesting coffins ("to make sure he never gets out again," according to one wag).

Napoleon Bonaparte, born on this day in 1769 in Ajaccio, was the son of a minor Corsican nobleman whose family had never bothered itself with the dirty business of soldiering. Were it not for Napoleon being packed off to study at a military academy at Brienne, France, Napoleon might have followed his forefathers' footsteps as a gentleman landlord; but Napoleon became a voracious student of military history, and after completing his studies he joined the French artillery as a second lieutenant.

He was an active Jacobin as the French Revolution began, and when Corsica declared its independence, Napoleon completely severed his ties with his homeland, seeing his best hopes for advancement in supporting the revolutionaries. He became the hero at the British siege of Toulon, directing the focused barrage which resulted in French victory, and at 26, was promoted to brigadier general. Back in Paris, he happened to be on hand when a group of angry royalist protesters threatened to interrupt the revolutionary constitutional convention; he ordered a "whiff of grapeshot," a single artillery volley, to be fired at the crowd, which dispersed them so quickly that Napoleon was rewarded with the command of the Mediterranean army in Italy.

Following a quick succession of victories, by the end of 1797 he controlled most of Italy and Austria, and set his sights on Britain by attempting to disturb its Indian trade with an assault on Egypt. Avoiding a losing battle against Lord Nelson's fleet, Napoleon stopped his onslaught and returned to Paris, used the strength of his heroic reputation to assemble key supporters, and staged a quick coup over the Directory then ruling France, installing himself as first consul and leader of the French at age 30.

As an administrator, he was fast and effective -- he cracked down on street crime, began mandatory military conscription, and consolidated his power with new constitutions in 1802 and 1804, giving much to the appearance of democracy and the "sacred rights of property, equality and liberty" while ultimately giving himself the title of "emperor" (literally crowning himself in a ceremony in Paris on December 2, 1804, snatching the crown out of the hands of Pope Pius VII). His Napoleonic Code standardized laws, abolished serfdom, and provided freedom of religion and free education; it was the precedent for the laws of modern France, as well as Belgium, Quebec and the Louisiana Territory.

Successful at home, he grew tired of British attacks and restless for world domination. He planned to attack Britain, but his fleet was drawn into a devastating fight with the British at Trafalgar (led by Nelson again, who died winning); so Napoleon decided to move to the ground campaign (1805-7) in which he defeated Austria and Russia at Austerlitz, Prussia at Jena-Auerstadt, and Russia at Friedland using widely spaced columns of troops who lived off the land and moved with astonishing speed. By 1808, much of continental Europe was in his control, which he delegated to his brothers and nephews to rule over as constituent kings. His luck ran out, however, with an unsuccessful attack on Spain (in which he lost 300,000 troops) and the ill-fated invasion of Russia in 1812; his prize after slashing and burning his way across Eurasia was a self-immolated, abandoned Moscow, with no provisions for the winter. In retreat during 1813, Napoleon fought brilliantly against the coalition of Russian, Prussian, British and Swedish troops, but was defeated at Leipzig. He resisted an offer of a peace treaty with the coalition, which only inflamed his enemies, bringing them marching into Paris in January 1814; within 3 months, Napoleon had abdicated and accepted exile on the island of Elba.

In March 1815, however, he escaped and entered France at Cannes; his old compatriot Marshal Ney, sent to arrest him by Louis XVIII, instead joined him, beginning 100 days of moderately successful battles against the coalition. By June 1815, he and his troops had lost their spark, and Napoleon suffered his last, most decisive defeat at Waterloo, at the hands of Wellington and Blucher. Having already irrevocably changed the map of Europe, he surrendered again and was this time exiled to a British island in the South Atlantic, St. Helena.

This time, the formerly irrepressible Corsican settled into his fate gracefully, spending his time tending to his flower garden, horseback riding and playing with the neighborhood children. The Napoleonic legend sprang up almost immediately, fed by indulgent assessments by Lord Byron, Heine, Stendahl, Hugo and Walter Scott who saw him as the stabilizing harbinger of post-monarchial liberty, but balanced by popular preoccupations with his physical and emotional shortcomings.

Napoleon died on May 5, 1821 on St. Helena.

Labels: France

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home