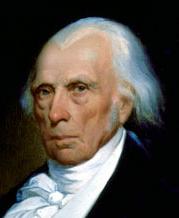

James Madison

James Madison could not have hoped to get himself elected to national office in the 21st century. He was a terminally shy, dour 5'-4" dweeb with a weak voice and a frostbite scar on the tip of his nose. Bob Newhart would stand a better chance of getting elected president today -- or Dennis Kucinich, for that matter. Even in the late 18th-early 19th century, some people had their doubts about little Jemmy. The colossal irony is that the engine of the process by which we choose our leaders today was the result of Madison's best life's work, as father of the U.S. Constitution.

Born on this day in 1751 in Montpelier, Virginia, young James Madison was a quiet but tireless and politically aware student at Princeton, graduating in just two years. He stayed on to study philosophy and Hebrew privately with Princeton president John Witherspoon, and returned to his father's home in Montpelier in 1772, half-heartedly pursuing law studies. When the Revolution began, he joined the militia, but was too frail for service. Instead, Madison rode the wave of nation-building, first as a delegate to the Virginia Convention to establish a plan for state government (1776), then as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates (1776-7) -- although he lost his seat in the next election because he failed to honor the custom of passing out whiskey to voters. He became the youngest member of the Continental Congress in 1780, and in his front-line support of the principles of strong central government with guaranteed fundamental freedoms, he found his capacity for leadership and began to form his political philosophy.

Back in the Virginia House of Delegates in 1784, he fought tooth-and-nail against Patrick Henry's attempt to establish the Episcopal church as the state religion. By 1787, with a career's worth of experiences with the squabbling loose affiliation of states under the Articles of Confederation and a commitment to personal liberties, Madison became a leading light of the U.S. Constitutional Convention -- as one of the principal draftsman of the document, a recorder of the Convention's proceedings, and a pragmatic advocate. Indeed, from the outside looking in, European commentators tend to credit Madison with being the most influential partisan in the creation of American political institutions and America's most important political philosopher.

He extended his influence after the Convention while the states debated the Constitution's ratification: he led the fight in Virginia against anti-Constitution forces led by his old nemesis Patrick Henry and, for the benefit of the national cause and for posterity, was one of the authors of the Federalist Papers, still the most often quoted commentary on the Constitution, with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay. Under the pseudonym of "Publius" (collectively and individually used by all three of them), Madison brilliantly articulated the case for the separation of executive, legislative and judicial powers, a structure he summed up with the notion that "Ambition must be made to counteract ambition." Henry kept Madison out of the newly created U.S. Senate, but Madison did win election to Congress, where he authored and pushed through the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, known as the "Bill of Rights" -- including the freedoms of speech, assembly and religion.

With the broad outlines of the new government drawn, the operating policies of Washington's administration began to cause rifts between the Federalist Hamilton and the states' rights views of Thomas Jefferson, leading Jefferson and Madison to form the Democratic-Republican Party, the forerunner of the Democrats, in 1792. Jefferson named Madison as his secretary of state in 1801, and as such Madison mainly concerned himself with piracy and British and French harassment of American ships, approaching the latter with an embargo against the two nations.

In a bit of poetic irony, during this period Madison's name graced the caption of the Supreme Court's first dramatic demonstration of its authority as the supreme arbiter of "constitutionality," Marbury v. Madison (1803), written by the Court's first great chief justice, John Marshall; in it, William Marbury, who had been appointed justice of the peace by President Adams prior to the end of his term but who had failed to receive his commission, sued Madison as secretary of state to Adams' successor, President Jefferson, to force him to deliver the commission. Marshall's opinion declared that Madison should have delivered the commission, but also that the Judiciary Act of 1789, the act by which Marbury had received his writ of mandamus against Madison, was void because it was unconstitutional -- thereby happily serving Marshall's dual objectives of establishing the authority of the Supreme Court and making Jefferson look foolish.

When Jefferson retired in 1808, Madison was his heir apparent for the presidency, and he won rather easily. As president, he revised his embargo policy by challenging either Britain or France to be the first to recognize the independence of American ships in exchange for an embargo of U.S. trade against the non-consenting nation; Napoleon jumped at the bargain, and Madison proceeded with an embargo against Britain. The embargo escalated into a declaration of war against the British in 1812. Although American military operations were mostly disastrous (notably in Madison's failed bid to conquer Canada, and in the British burning of the White House and the Capitol in August 1814), the war ended in a draw. Madison was faulted for the poor effort, but the shutdown of foreign trade during the war did manage to spark the native economy and ultimately had the effect of reducing American dependence on the economy of Britain.

Madison left office after his second term in 1817 and returned to Montpelier. He spent his final years farming, covering the gambling debts of his spendthrift stepson, serving as rector of the University of Virginia, and promoting the gradual abolition of slavery. He died at Montpelier on June 28, 1836.

Incidentally, James Madison was a second cousin of the 12th U.S. president, Zachary Taylor.

Labels: American Politicians, Juris History, Marbury v. Madison, US Presidents

1 Comments:

I believe young Meriwether Lewis thought so well of Jefferson's secretary of state that he named a Montana river for him. That river today, the Madison, is one of the best fly-fishing bodies of water in North America.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home