Prisoner without Fingerprints - The Mystery of Thomas Malory

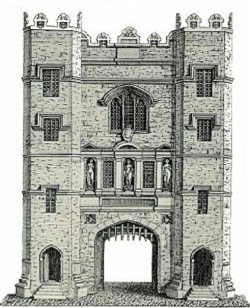

Tomorrow we remember the 535th anniversary of the death of an obscure member of Parliament and minor English landowner who styled himself as a knight, but who paradoxically (at least from the comfort of our 21st century armchairs) spent a good deal of his life in prison -- including London's Newgate Prison, pictured at left.

During his tumultuous life, this troublemaker was accused of committing, during an alleged 18-month crime spree, the attempted murder of the Duke of Buckingham, rape, extortion, cattle-rustling and church-robbing. He was eventually arrested, and while awaiting trial on these offenses, he escaped from the prison at Coleshill by swimming the moat -- but was later brought to London and held by the Sheriff of London in 1452. This ill-framed knight spent most of the next eight years in London prisons (except for brief periods, including one following another dramatic armed escape) without being brought to trial, apparently the victim of the events surrounding the War of the Roses, the English Civil War in which King Henry VI was twice deposed in favor of Edward, Duke of York (later Edward IV). It appears that the fellow was perceived to be dangerous (at least in his ability to cause mighty trouble with scores of armed men raised on short notice) to Henry VI's Lancastrian supporters, given that the length of his imprisonment without trial seems to have been a record even by medieval standards. As Edward's fortunes improved, he was released from prison, and later he took advantage of a general pardon granted by King Edward to expunge his prior charges; however, it appears that around 1467 he ran afoul of the Yorkists, was imprisoned again and specifically excluded from a royal pardon.

And scholars have spent 100 years or so trying to figure out whether they should care at all about Thomas Malory of Newbold Revel, who died on March 14, 1471 in London.

For better or for worse, it is no secret that critics and popular readers of modern literature alike crave psycho-biographical details of authors. Some might dismiss this as gossip-mongering, and perhaps it is. Yet, if TV, the best-seller list and the magazines in our supermarket checkout lines are any measure of our intellectual predilections in this age (and I submit that they probably are), "personality" seems nevertheless to be the hook that most often engages the modern mind in its approach to almost any cultural phenomenon – from art to politics, from history to ethics, and so on.

For those who strive in this age of gossip to appreciate the literature of another age, however, psycho-biographical details can be scant. English historical records prior to the 17th century, for example, are pointedly unhelpful in this regard concerning most people, celebrities included.

For the biographically-informed analysis of the works of two of the greatest English authors prior to the middle of the 17th century, however, a relatively vast amount of documentary material has been uncovered: Geoffrey Chaucer and William Shakespeare stand today virtually as living, breathing, three-dimensional beings. We can chart the activities of Chaucer throughout London in the 14th century with a surprising amount of detail, and we even have Hoccleve's manuscript drawing of an elfin Chaucer to assist us in imagining him living out these activities – a gentle cartoon portrait that lamentably inspires so many casual readers of The Canterbury Tales to think of Chaucer as a kind of Dr. Seuss writing in Middle English.

And Shakespeare? Yes, there are portraits and plenty of known details about the life of the great playwright. Even the poor, deluded Baconians, who (like escapees from a Monty Python sketch) claimed that Francis Bacon and his buddies actually wrote the plays and sonnets, never doubted Shakespeare's existence or his general station in life. They merely argued, through a rendering of the available biographical evidence concerning Shakespeare, that the "vulgar, illiterate [sic] . . . deerpoacher" could not have written Hamlet, Macbeth or Othello. Lest we think that the tabloid-infused cult of personality is purely a 20th/21st century invention, the Baconians remind us of the long heritage of celebrity gossip.

Sandwiched chronologically between the brilliant careers of Chaucer and Shakespeare is the creation of a well-known collection of tales which, while revealing a hand less virtuosic than Chaucer's or Shakespeare's, has nevertheless captivated centuries of readers and spawned countless imitations, variations and reverberations: the 15th century English prose rendering of a cycle of French romances concerning King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table known as Le Morte Darthur. These powerfully-told tales reveal a world in which romance and chivalric virtues are continually beset by violence and brutishness. If Le Morte Darthur had been an anonymous medieval work – like so many others of the age – scholars and fans would be left sorting through cultural stereotypes and wondering whether the author was a man or a woman, a shepherd or a priest, a Londoner or a northcountryman. But a name is attached to the damned thing -- "Thomas Malory, knight" -- and with the name comes an untidy set of ambiguities.

In William Caxton's 1485 printed edition of Le Morte Darthur, the following curious words appear as a kind of closing benediction:

I praye you all jentylmen and jentylwymmen that redeth this book of Arthur and is knyghtes from the begynnyng to the endynge, praye for me whyle I am on lyve that God send me good delyveraunce. And when I am deed, I praye you all pray or my soule. For this book was ended the ninth yere of the reygne of King Edward the Fourth, by Syr Thomas Maleore, knight, as Jesu helpe hym for His grete might, as he is the servaunt of Jesu bothe day and nyght.

In another late 15th century manuscript of the work, the following statement appears at the end of one of the first tales:

And this booke endyth whereas sir Launcelot and sir Trystram's com to courte. Who that woll make any more lette hym seke other bookis of kynge Arthure or of sir Launcelot or sir Trystrams; for this was drawyn by a knight prisoner sir Thomas Malleorre, that God sende hym good recover.

No portrait, no fingerprints, no positive identification – only the tantalizing detail that Sir Thomas Malory was a knight and a prisoner.

In 1548, a mere eighty years after Le Morte Darthur was written, an antiquary and cataloguer named John Bale declared that Malory was Welsh and that he was born near the River Dee at Maloria in Wales. Bales gave no other details, and failed to pinpoint exactly where Maloria was – a drafting decision that has frustrated subsequent scholars who have striven in vain to find it. Bales' assertion, however, was given new life by John Rhys, editor of an 1893 edition of the Morte, who proposed that "Maelore" probably referred to one of two districts that straddle the border of England and North Wales, and that the Morte's author was probably a namesake of Edward ab Rhys of Maelor, a 15th century Welsh poet.

A few years later, in the rush perhaps to prove Rhys' naivete, scholars began to pursue the frozen trail in earnest. All told, seven distinct "To Tell the Truth" candidates for the real Sir Thomas Malory have since taken shape:

• The ghostly, probably apocryphal Thomas Malory of Maloria, Wales;

• Thomas Malory, rector of Holcot, Northamptonshire;

• Thomas Malory esquire of Papworth St. Agnes, Cambridgeshire;

• Thomas Malory, laborer, of Tachbrook Mallory, Warwickshire;

• Thomas Malory of Long Whatton, Leicestershire;

• Thomas Malory of Hutton Conyers, Yorkshire; and

• Our troublemaker, Thomas Malory of Newbold Revel, Warwickshire.

It has been the curse of Malory scholars that there were several men drifting around England in the 15th century who shared the name "Thomas Malory."

Despite a century of heated debate, however, none of the Thomas Malorys who have been proposed have been positively identified as the author of Le Morte Darthur. Nevertheless, a kind of consensus has emerged that Thomas Malory of Newbold Revel is the most plausible candidate to be the author of the Morte, a point of view most definitively advanced by P.J.C. Field in The Life and Times of Sir Thomas Malory, who argues that none of the other Thomas Malorys can be proven to have been alive at one of the key moments of history identified by Malory scholars.

The details of this Malory's life are unsettling to some readers of Le Morte Darthur. Much like Baconians believe Shakespeare was not clever enough to have written his plays, some see Thomas Malory of Newbold Revel as not being gallant or chivalrous enough to have written about gallant and chivalrous knights.

During his final period of imprisonment (so the theory goes), our Malory allegedly finished Le Morte Darthur. It has been asserted that upon Henry's brief reaccession to the throne in 1470, Malory was released by his former enemies the Lancastrians, and died in good enough circumstances to be buried in London's most fashionable church, Greyfriars, under a marble slab which described him as a knight. Apart from Malory's gift for troublemaking, perhaps the fickle fortunes and moods of his protectors and a deep desire on his own part to find an ever-elusive "good lord" (something the itinerant knights in his tales seemed to take very seriously) might explain the bizarre twists of his life.

Labels: Arthuriana, Literature, Shakespeare

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home