Recently I’ve had the chance to see some old major league pitchers at work. And by old, I mean guys who are just about my age. On a visit to Fenway two weekends ago, I saw Bosoxer Curt Schilling pitch 5 and a third innings against the Orioles. He gave up 4 runs and left a tie game, but looked pretty good for a 39-year-old throwing 95 pitches. Last weekend, I also caught the Mets’ Tom Glavine, on TV and on XM, facing the Yankees and hurling his 295th victory at age 41; and I went to PNC Park on Sunday to see Randy Johnson, age 43, throw 10 strikeouts in 5.2 innings to beat the Pirates 5-2.

It’s a cliché that advanced age is associated with slowness – old preachers give slow sermons, old film directors make slow movies, old grannies drive slowly down the right lane of the parkway -- but watching these pitchers work belies this. Glavine kept the game moving along quickly, pitching 101 pitches before the late-inning rain started to slow the game down; after some sloppy relief pitching, the game finally finished up in about 3-1/2 hours. The Big Unit was even faster in dispatching the Bucs in a game that wound up lasting only 2-1/2 hours. Even Schilling worked pretty quickly; it was only after he left the mound that the 7th and 8th innings of the Red Sox-Orioles game seemed almost like the second independent half of a double header all by themselves.

Johnson’s victory occurred in a game that was faster than the average major league game, but back in 1916, a few fans in Asheville, North Carolina were on hand to see what is now considered to be the fastest game in the history of professional baseball.

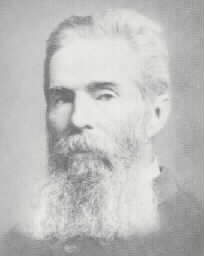

The Asheville Tourists played in the inaugural season of the Class D North Carolina State League as the Asheville Mountaineers in 1913. After suffering a last place finish in 1914, the club changed its name to the Tourists for the 1915 season and battled their way to first place under the helm of a popular slick-fielding infielder-manager, John P. “Jack” Corbett, finishing 5-1/2 games ahead of the Durham Bulls. That year, a 15-year-old future novelist named Thomas Wolfe caught Tourist fever, and spent the season serving as Corbett’s bat boy, shagging pre-game pop flies and disappearing into the bleachers once the game would begin.

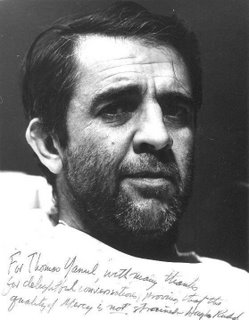

Recalling his days at Asheville’s Oates Park (pictured above), Wolfe later wrote to baseball writer Arthur Mann:

“… [I]n the memory of almost every one of us, is there anything that can evoke spring – the first fine days of April – better than the sound of the ball smacking into the pocket of the big mitt, the sound of the bat as it hits the horse hide; for me, at any rate, and I am being literal and not rhetorical – almost everything I know about spring is in it – the first leaf, the jonquil, the maple tree, the smell of grass upon your hands and knees, the coming into flower of April. And is there anything that can tell can tell more about an American summer than, say, the wooden bleachers in a small-town baseball park, that resinous, sultry and exciting smell of old dry wood.”

But Wolfe well understood the inherent bittersweetness of minor league baseball. Nebraska Crane, a character in Wolfe’s

The Web and the Rock and

You Can’t Go Home Again, was apparently based on Corbett, an Ohio-born minor league journeyman who never ultimately made it to the bigs. Wolfe wrote about Corbett more directly in

Look Homeward, Angel:

“Pearl juggled carefully the proposals of several young men during this period. She had the warmest affection for a ball player, the second baseman and manager of the Altamont [i.e. Asheville]

team. He was a tough, handsome young animal, forever hurling his glove down in despair during the course of the game, and rushing belligerently at the umpire. She liked his hard assurance, his rapid twang, his tanned, lean body …”

The Tourists won the first half of the 1916 season, and looked poised to repeat their 1915 triumph; but the elation of Thomas Wolfe's boyhood hero Jack Corbett turned to resignation as the club pulled into August. Despite leftfielder Jim Hickman’s league-leading .350 batting average, the Tourists were in 4th place, hovering just above .500 ball on August 30, the last day of the season. The Winston-Salem Twins were in town for the final game, but the Charlotte Hornets had already clinched the league title, so the Twins were definitively in second place for the year.

The game was scheduled for 2 p.m., but apparently the Twins were anxious to call it quits for the season; they wanted to catch a 3 p.m. train back to Winston-Salem. So Corbett and Twins skipper Charlie Jones apparently entered into a gentlemen’s agreement to start the game a half hour early and to keep it as short as possible. After all, they reasoned, it was a meaningless game as far as the standings were concerned. Other teams playing meaningless games at the end of the season in those days were wont to run onto the field wearing clown suits or ladies’ bloomers, so the idea of a fast game was a pretty tame shenanigan by comparison.

Two hundred fans showed up at Oates Park for the game – not many for a ballpark that could hold 1,200, but then again, most of the town’s baseball fans probably hadn’t gotten the message that the game was going to start early. According to

Sporting News writer Bob Terrell, Thomas Wolfe was allegedly among those present.

The

Asheville Citizen summed up the ensuing game as a “farcical contest.” The paper described the manner of play:

“Nobody let a baseball get past. Everyone hit the first ball pitched … Nobody was left on the bases. If a man hit and didn’t come home, he contrived to get tagged out by overrunning the bag. Before the last man in an inning had been called out the players were on the run changing sides in the field. Along about one of the innings, some Twin player rushed to bat and [Tourists’ pitcher Doc]

Lowe pitched the ball with no one in to catch. It was hit to center field, a fair single, but Nesser [one of the Twins’ outfielders]

grabbed it on the bounce on the way into the bench and threw his team mate out at second.”

Lowe gave up two runs in the first inning; umpire Red Rowe showed up to officiate the game in the 4th inning. In the 7th, the Tourists managed to score one off the Twins’ ace, Whitey Glazner; and after 2 more innings, the two sides mercifully put the game out of its misery. Glazner (who later pitched adequately for 5 seasons, 3-1/2 with Pittsburgh and 1-1/2 with the Phillies) got the win, helping him to attain a league-leading .750 winning percentage for the season. The game was finished in a mere 31 minutes – two minutes before it was actually scheduled to start.

Perhaps the operative base running phrase of the day, with all due deference to Mr. Wolfe, was “You

can go home again, but we’d prefer that you don’t, ‘cause we’re trying to wrap this up early.” Imagine your dismay, though, if you showed up at the ballpark looking forward to the last game of the season, only to find the players heading to the showers.

No one was particularly pleased about the day’s display, and Tourists president L.L. Jenkins jumped to his feet after the game and shouted a valedictory, promising that every paying customer would be refunded his or her money. The

Citizen noted that women, in particular, were almost unanimous in calling the entire spectacle “perfectly horrid.”

Jack Corbett left Asheville after the 1916 season, and it turned out to be none too soon. While Corbett was busy managing the Columbia Comers to the South Atlantic League pennant in 1917, the Asheville club folded on May 17, 1917. The North Carolina State League itself shuttered two weeks later, a domestic casualty of World War I. Baseball would not return to Asheville for another seven years.

Although Corbett never made it to the big leagues, his name lives on in baseball. As early as 1939, Major League Baseball adopted Corbett’s patented design for the bases used on the field; now all 30 major league teams use “Jack Corbett Hollywood Base Sets,” with a tapered lip on the bottom of each base to grip the infield dirt, and a six-inch stanchion to anchor it. Corbett passed away in Van Nuys, California in 1973, at the age of 85.

Bill James says that baseball games have gotten too long, observing that “the wasted time inside baseball games dissipates tension, and thus makes the game less interesting, less exciting, and less fun to watch.” In an age in which everyone wants everything yesterday, baseball’s slowness is one of the things I appreciate most about the game. Certainly the fans present at Oates Park on August 30, 1916 were not treated to baseball that was interesting, exciting or particularly fun to watch. I do enjoy watching the studied efficiency of a veteran pitcher like Schilling, Glavine or Johnson, but give me a wild rookie pitcher and some guys who can foul off almost every strike, and that will suit me fine. My enjoyment of baseball is not measured by how exciting any particular game is; it is measured by being within the milieu of those sounds, sights and smells that Thomas Wolfe celebrated – to sit back, without any concern for the clock, and to take a break and enjoy an American rite of spring.

Labels: Baseball, Literature