Casual Summer Romance

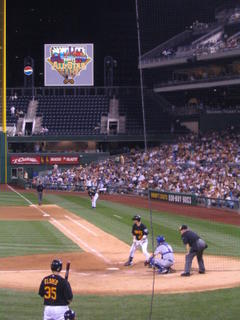

My wife and I and a couple of our friends enjoyed a ballgame at PNC Park the other night. We didn’t arrive at our seats until the 5th inning was almost over, however, and I only got to see future HOFer Greg Maddux throw a couple of pitches before he was yanked, but it was a nice end-of-summer evening. The ballpark looked great, and there were fireworks afterwards. Never mind that my wife had to ask me who won the next morning. (Cubs over Pirates, 7-3, if you’re counting.)

Yes, as a long-time baseball fan, I do feel somewhat guilty about having such a cavalier attitude about the game these days. But if I were to portray myself as some kind of studly sporting lothario for a moment, Major League Baseball has become, for me, like a casual summer romance – available, forgettable.

Perhaps it is just a phase, but my interest in today’s game has been in decline ever since I spent 7 years of my professional career as a lawyer representing the City of Pittsburgh, working on the seemingly endless series of transactions and decisions leading to the completion of PNC Park in 2001. Being inside the business of baseball is a lot like being inside the sausage-making machine, unfortunately – not a pleasant experience. (More about that, perhaps, in a later entry.) And while I am literally swelling with pride as I sit in PNC Park in the beautiful night air, for the splendid creation that it is and the small role I was able to play in its birth, I am not connecting with the Major League game the way I used to.

Some of my friends have let on that Major League Baseball hasn't been the same for them, either, even without the experience of having looked at the Pirates’ financials for several years. This year, the biggest story in baseball has been steroids. Last year, at least we had the improbability of the Red Sox’ World Series triumph to buoy our spirits; but in 2003, the biggest stories in the sport were Sammy Sosa’s corked bat and Ted Williams’ frozen head. We’ve had a few disappointing seasons, my friends and I.

Actually, Major League Baseball as a cultural institution has been on steroids for some time. Just look at the numbers. Baseball numbers in years past were manageably man-sized numbers, even when superhumans were their authors. Two hundred hits, 3,000 hits . . . batting .300, or even .400 . . . smashing 60, then 61 home runs . . . 714, 755 across a man’s career. . . 20 wins, 300 strikeouts . . . a no-hitter (zero is surely a manageable size). Contrast those comfortable numbers with some of the significant numbers that spurt from the sports pages today – $56 million for local TV rights, a $100 million dollar player contract, $248 million to build a ballpark – even the fact that the word “million” could appear anywhere in the same sentence with a word ending in “park” is an indication of how baseball may have lost its human scale.

It's a good bet that Major League Baseball may have completely lost all connection to its roots. It is unlikely that the players and fans of baseball as it was played in the 1870s, for example, when the game became a league sport, would feel any sense of kinship with today’s game.

Let’s remember this: games are never just games. They are fundamentally about other things -- and through ritual disguised as "play," games function as a way in which society can fill specific spiritual voids.

In the 1870s, baseball -- a summer sport, played in larger Midwestern and Eastern factory cities, which came of age with the rise of Urban America -- became popular in part because the feel of it evoked a nostalgia associated with the rural agrarian past. It’s staying power came in no small part from its visceral attributes: the sensation of holding a hand-wound orb of jute, covered by rough leather, between one’s thumb and the curve of one’s forefingers – a soft shape, but solid to the touch, like a chestnut; the cracking sound of wood making contact, echoing to the outer fringes of a quiet meadow; the smell of fresh grass; the scraping of crumbs of earth beneath one’s feet.

As Bill James glibly observes, in the 1870s the game was played by “(e)ntrepreneurs, Irish, and people from Brooklyn, Philadelphia and Baltimore.” First and second generation Irish, first and second generation factory boys, fresh from the family farm (or the memory of it, passed from father to son), collecting together on weekends in green parks to “reach home,” to wash away the industrial soot and grime, breathe in some clean air, and play in a pastoral paradise once again. The entrepreneurs to which Mr. James refers were simply the clever fellows who turned baseball into a modest money-making venture, consciously or unconsciously exploiting that primal, spiritual need of the newly-minted urbanite to return to the wheat fields.

Fast-forward to 21st century America, and we can see that the underlying function of baseball has become alienated from that which once attached it to the collective consciousness. Today, most of us have grown up in cities or suburbs, and any lingering memory of wheat fields in us is no doubt deeply submerged within some obscure corner of our chromosomes, along with spearing a woolly mammoth. We may still hear the evocative crack of the bat, but the other sensations have long since died out, replaced at the ballpark by the Jumbotron, Technicolor logowear and hip-hop interludes.

It’s colorful and boisterous, and it can be great fun. And I don’t begrudge anyone making a good dime from doing something they love -- more power to them. The thing is, I think there is a growing number of people each passing year who wonder what part of themselves is supposed to be fulfilled by the Major League game, apart from that portion of their minds that is already affected by any modern spectacle, almost indistinguishably from the others that compete with it on daily basis – from cruising the mall, to going to a concert, to watching cable TV or listening to your iPod.

I don't mean to suggest that Major League Baseball needs to mean to us what it meant to people in the 1870s. However, if it is not fundamentally “about” anything that is different than those other diversions, then Major League Baseball risks being superfluous.

I know I’ll come back. I always do.

In the meantime, I have the intimacy and immediacy of minor league ball to keep me occupied, cut down to a manageable human size, with human-sized foibles. I get hours of fun from poring over the season-by-season numbers put up by a Tom Seaver, a Sandy Koufax, a Roberto Clemente or a Willie Mays. Their vapor trails keep the game alive for me. And I do get a thrill from putting on the old Rawlings glove, smacking it with my fist and playing catch.

I just hope that when I do return, there’ll be enough of its old essence – that stuff I love about the game – that’ll still be recognizable in it.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home