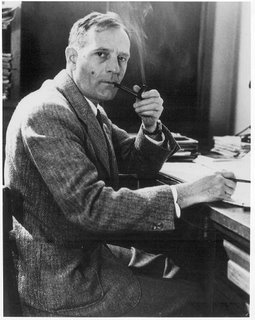

Twain

"My books are water; those of the great writers are wine. Everybody drinks water." -- M. Twain.

Considered by many critics to be the greatest American writer, there are some who are tempted to see him as simply a writer of humorous children's books such as the boyhood reveries The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884). Although his sense of humor was irrepressible (sometimes to his own chagrin), Twain was raised in an atmosphere of Presbyterian guilt, however, and he spent much of his literary life attempting to throw off the yoke of his conscience through cynical and increasingly dark and bitter writings. His writing is deep and rewarding at both ends of the light-dark spectrum.

Samuel Clemens -- born on this day in 1835 in Florida, Missouri -- spent his boyhood on the banks of the Mississippi, and his boyhood experiences are a recurring backdrop for his work, not only in Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, but in Life on the Mississippi and many magazine articles. He worked as a riverboat pilot for about 4 years, but eventually became an itinerant printer, settling with his brother Orion in Keokuk, Iowa, and moving with him to Nevada in 1861 when Orion was named secretary to the governor of Nevada, James Nye.

There Clemens became a full-time reporter, and shortly thereafter began to use the pen name "Mark Twain" (a resurrection of the pen name of an old riverboat captain, derived from a warning of shallow water on the river) to distinguish his lighter pieces from his routine political reporting. He moved to California in 1864, where he continue to work as a reporter; but there his fiction was given encouragement by Bret Harte and he published a story which would change his life, "Jim Smiley and his Frog" (1865), a comic report of chicanery involving a wager over jumping frogs which earned Twain a national reputation with its colorful use of Western country vernacular and sly, irreverent review of the differences between genteel Easterners and rough Westerners. Meanwhile, he continued to work as a reporter, although his byline was now becoming more prominent, covering the Hornet shipwreck in the Sandwich Islands in 1866; and after a steamship expedition to the Holy Land he published The Innocents Abroad (1867).

He returned from the Holy Land to New York City to find that he was a celebrity, selling out the Cooper Union with a humorous lecture on the Sandwich Islands. After marrying Olivia (Livy) Langdon in 1870, Twain began to concentrate on making money. At his father-in-law's urging, Twain bought into the Buffalo Examiner and marketed his books throughout the country with traveling salesmen who could reach people who would not find themselves in a bookstore.

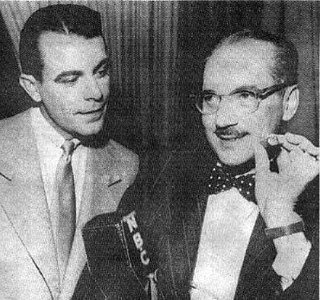

In support of his books, Twain often traveled himself, on an almost perpetual book tour, lecturing to appreciative audiences and perpetuating his image as the wild-haired (and eventually white-suited) smart-aleck, sage and celebrity -- an image appropriated in the 20th century by such writers as Kurt Vonnegut, Tom Wolfe and Norman Mailer. Livy, whom he loved deeply, appealed to his Presbyterian side, and was responsible along with his somewhat blue-nosed occasional editor, Mrs. Fairbanks, for toning down his comic irreverence at times; while Twain toured, Livy would send him copies of Henry Ward Beecher's sermons to develop piety in him. It did not; it did little more than to inflame his resentment over duties of conscience, a theme which would occupy a greater role in his work as he grew older.

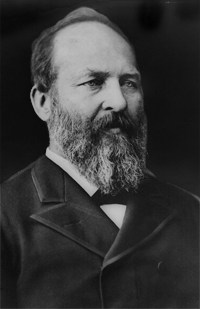

During the 1870s he poured his energies into the Examiner as well as writing humorous short stories and other pieces for a New York City journal, the Galaxy (including Twain's personal favorite among his own short works, a hilarious "burlesque map of Paris" which allowed him to poke fun at his days as an ink-monkey). Many of these short pieces (including such works as "Political Economy," 1870; "The Stolen White Elephant," 1878; "The £1,000,000 Bank-Note," 1893; and "The Man that Corrupted Hadleyburg," 1900) ended up in collections which Twain later published and circulated. In keeping with his obsession for marketing and investing, he developed the "Mark Twain Scrapbook," a set of empty gummed pages with special tabs and other features which became a popular dime store item, started his own publishing company (which, notably, published the memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant and yielded $400,000 to his bankrupt heirs); and threw away $200,000 on a typesetting machine invented by James Paige which never caught on.

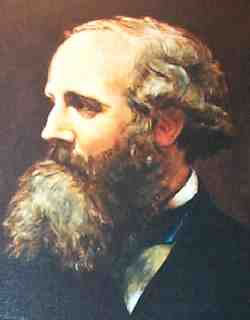

Known for his vernacular writing and his spoofing, Twain was not thought to be a serious writer by the Eastern establishment, William Dean Howells took up his cause, published his work in the Atlantic and introduced him to some of the great Eastern writers. On the occasion of John Greenleaf Whittier's 70th birthday, Howells invited Twain to speak to the assembled crowd, which included three-named literary gods Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Oliver Wendell Holmes; Howells recalled that the speech was a "disaster," that Twain's irreverent burlesque merely succeeded in freezing the room, and Twain hurriedly followed with letters of apology to each of them, although none of them had actually taken offense to anything he had said.

After the success of The Prince and the Pauper (1881) and Huckleberry Finn, Twain continue to publish popular novels including A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court (1889) and The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson (1894); The Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (1895) failed to make as much of an impression, however. Twain's later work, particularly that written after the death of Livy in 1904, has been characterized as having been "written from the grave," full of regret and misanthropy with occasional flashes of Twain's signature wit, including: The Diaries of Adam and Eve (1904-6), the philosophical dialogue What is Man? (1906), Extract from Captain Stormfield's Visit to Heaven (1909) and The Mysterious Stranger (1916, published posthumously). Twain died on April 21, 1910 in Redding, Connecticut.

Labels: Literature