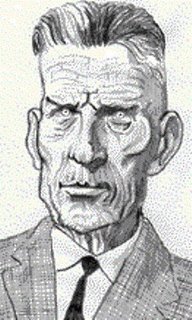

Beckett

Samuel Beckett did not see his breakthrough as a writer until he was 47; but with the performance of his play Waiting for Godot in 1953, Beckett placed his indelible stamp on the shape of 20th century drama.

He was born on this day 100 years ago, in 1906 in Foxrock, Ireland. A shy young man, Beckett was an accomplished cricket player and boxer who thought he was destined for a career in chartered accountancy until he found he had a facility with modern languages while at Trinity College in Dublin. From Trinity he went to the Ecole Normale Superieure in Paris, where he met James Joyce and became one of his assistants. Joyce exemplified for Beckett an extraordinary dedication to one’s craft and encouraged Beckett with his own writing. Their friendship ended, however, over Joyce’s daughter, Lucia, a schizophrenic who fell obsessively in love with the disinterested Beckett; to avoid the uncomfortable situation, Joyce simply refused to see Beckett any more about the time Beckett was supposed to return to Dublin to finish his Trinity College thesis in 1930.

In Dublin, Beckett became seriously depressed, and was sent to live with his aunt’s family in Kassel, Germany for a change of scenery. From there Beckett returned to Paris to make a living at writing, but was turned away following the assassination of French president Paul Doumer in a police crackdown on foreigners, and eventually ended up in London to write and seek psychoanalysis.

In 1934 he published his first collection of short stories, More Pricks Than Kicks, which received critical praise but did not sell well. Continuing to suffer from clinical depression, he nonetheless worked away at a novel, Murphy, which was published in 1937. Shortly thereafter, he had a brief affair with Peggy Guggenheim before being brutally stabbed in the chest in a random attack in Paris; while recovering he met Suzanne Deschevaux-Dumesnil, a pianist who became his life-companion (they married in 1961). Murphy did not bring Beckett his exepected recognition, but he continued to write as World War II approached, and in 1940 he became a member of one of the first French resistance groups. When the Nazis infiltrated his group, Beckett and Deschevaux-Dumesnil escaped to non-occupied southern France. After the War he received the Croix de Guerre and the Medaille de la Resistance for his resistance efforts, and wrote two more novels while shuttling back and forth between Dublin and Paris.

Beckett turned to writing drama to relieve himself from writer’s blocks while trying to write prose. He wrote Waiting for Godot (in French) in a little over three months at the end of 1948, a spare piece about two down-and-out nonentities, Vladimir and Estragon, who are waiting for someone named Godot with whom they apparently have an appointment; as Godot continually fails to show, they consider suicide, but then acknowledge that they have done their best in waiting, and end the play in resignation, silently facing the audience. The original "show about nothing" (a la Seinfeld), Beckett’s play departed from the exalted language of French theater of the time, instead using an ordinary conversational tone, and it combines accents of broad music hall comedy (showcasing the comic skills of vaudevillian and Wizard of Oz "Cowardly Lion" Bert Lahr in the American premiere) with a moral bleakness to define a new genre of absurdist tragi-comedy.

Encouraged by the success of Godot, Beckett became a more confident and prolific playwright, and all but gave up novels. In his plays Endgame (1958) and Krapp’s Last Tape (1960), Beckett continued to explore the desolate spirit of humankind -- mournful yet at the same time beautiful, wryly commenting on the brutalities of time, memory, longing and familiarity. Happy Days (1961), the story of a woman buried in sand up to her waist, amusing herself with various objects while her husband reads the newspaper behind the sandpile, carried through similar themes in an even more broadly absurd setting. In the late 1960s, his work became known for its almost outlandish brevity, stretching the boundaries of theatrical expression with Breath (1970), a play of 120 words that lasts 35 seconds, and Not I (1973), a 16-minute play. He flirted with cinema on his only trip to the U.S., making Film (1965) with Buster Keaton.

He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969 for "a body of work that, in new forms of fiction and the theatre, has transmuted the destitution of modern man into his exaltation." Beckett died on December 22, 1989 in France.

Labels: Literature, Psychoanalysis, Theater

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home