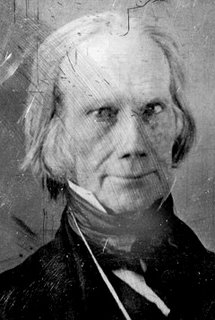

Henry Clay

"Mr. Clay is not great in himself alone. He combines and directs the greatness of others, and thus, whatever direction he takes, he moves with a resistless might. The secret of all this . . . is to be found in that most potent of all human influences, a true and ready sympathy . . . There are no barriers between his heart and the heart of others." -- Boston Courier, February 10, 1848.

150 years after his death, Henry Clay is mostly remembered as a big-time political loser, the man who unsuccessfully sought the presidency (again and again) and sought to save face by declaring, "I would rather be right than president." The other lingering image is that of the great compromiser, which in today's partisan parlance is tantamount to being convictionless. Anything but convictionless, in his day his efforts to preserve the union were thought to be heroic, and far from being a political loser, he enjoyed extraordinary power, second only to the president, wielding it in the service of a vision of America's future as a powerful, industrially self-sufficient state.

Clay was born on this day in 1777 in Hanover County, Virginia. As a young man, he was inspired by the oratory of Patrick Henry and became a passionate, unstudied master of rhetoric. He had little patience for his studies, but somehow managed to stumble through a course in law with George Wythe. After being admitted to the bar, he moved to Kentucky, where he underwent a slight political conversion, forsaking the agrarian-centered policies of Jeffersonian republicanism for the values of the Kentucky merchant class -- although Clay always maintained that he was faithful to Jefferson's principles.

Because of his speaking ability and personal charisma, he was quickly led into politics, being elected to serve an unfinished term in the U.S. Senate in 1803. His reputation was almost derailed by former vice president Aaron Burr, who asked Clay to represent him in his treason indictment. Although Clay managed to have Burr's case thrown out for lack of evidence, after Jefferson issued a proclamation of warning against Burr it soon became apparent that Burr had truly been engaged in a conspiracy to start a new country in the West, and Clay had to admit his error in taking Burr's case.

After serving some years in the Senate, Clay turned to the House in 1811 (which he found better suited his more rambunctious style) and was immediately elected speaker. As a rookie speaker, Clay was apparently not confined by tradition: rather than being a mere traffic cop, Clay exercised total domination over House procedure, deciding when and if bills would be referred to committees which he himself chose, and reserving other procedural advantages. Nevertheless, his leadership was received with affection, and he served for speaker longer than anyone else in the 19th century (10 years).

After a few years spent negotiating the peace with England after the War of 1812, Clay returned to the House urging protectionist tariffs to foster American industry (as a way of waging war on the protectionist policies of other nations). With a paternalist view with respect to American commerce he supported the National Bank, the National Road and other federal commercial initiatives (a comprehensive program he dubbed the "American System," a name borrowed from Jefferson), as well as independence for Latin America (his speeches were translated into Spanish and read as inspiration to revolutionaries).

He ran for president 3 times. In 1824, he came in 3rd in the popular vote, but 4th in electoral votes behind Andrew Jackson, John Quincy Adams and William Crawford, and through his efforts in the House he swung the election to Adams in the run-off. Shortly thereafter, Adams appointed Clay as his secretary of state, giving rise to charges of a "dirty bargain" between Adams and Clay which Clay would have to live down during each successive campaign. In 1832, Clay hoped to make Jackson's termination of the National Bank a decisive issue in the campaign, but Jackson was too popular, and Clay lost with 49 electoral votes to Jackson's 219; after the election, Clay pressed for the censure of Jackson over the National Bank termination. Clay was nominated by the Whigs in 1844 to face James K. Polk, but appeared weak when published letters seemed to indicate that he was waffling on the annexation of Texas (Polk barely won the popular vote).

More important than his three presidential defeats, Clay acted decisively to preserve the union on three occasions. He engineered the Missouri Compromise in 1820 (permitting the admission of Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state to maintain the regional balance of power), the Compromise Tariff of 1833 (which kept South Carolina from leaving the union over tariff issues) and the Compromise of 1850 (admitting several free states and requiring the federal government to take an active role in returning fugitive slaves to the South). The latter compromise was the last integrated effort to resolve the slavery issue, and while it did so temporarily, it also fractured the Whig Party, precipitating the rise of the anti-slavery Republicans.

If nothing else, Clay's efforts to forestall the inevitable conflict over slavery at least allowed the issue to simmer while awaiting a president with the fortitude and resolve to end the issue forever. One shudders to think what might have happened had the Civil War erupted on Millard Fillmore's watch as opposed to Abraham Lincoln's. As to his own view of slavery, although he owned slaves, he abhorred the institution, and was one of the earliest white politicians to recommend the repatriation of African-Americans to Africa, a movement supported by some African-American leaders at the time.

He died of tuberculosis on June 29, 1852 in Washington, D.C.

Categories: American-Politicians, Presidential-Campaigns

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home