Pynchon

Although his labyrinthine fiction has been accused of being nearly incomprehensible by some, Thomas Pynchon -- born on this day in 1937 in Glen Cove, Long Island -- is undeniably one of the most important authors of the last century.

An engineering student who switched to literature while at Cornell, perhaps following the lead of his charismatic friend, Richard Fariña, Pynchon published his first novel, V, in 1963 -- a darkly humorous odyssey of a man obsessively searching for the identity of a mysterious person or thing referred to in his father's diary as "V." In this work, as in his subsequent works, Pynchon's hero attempts to make sense out of the factual and experiential chaos of modern life by "grouping the world's caries into cabals." As the canvas upon which this organizing principle of paranoia is depicted in Pynchon's works, he delights in revealing the chaos: he eagerly infects his noisy world with allusions which grow dizzyingly encyclopedic in their Internet-like linkings, from comic books to Eastern philosophy to Busby Berkeley to Wagnerian operas to hard physics -- including, above all, Clausius' Second Law of Thermodynamics, Maxwell's Demon and Planck's quantum physics, scientific concepts which Pynchon raises to the level of defining contemporary metaphors.

Intensely private, Pynchon gives no interviews and permits no photographs of himself to be released (the only known photos of him were taken when he was a teenager, in college or in the Navy); even his official dossiers seem to have vanished. Attempts to draw him out have met with dryly humorous regrets; to Norman Mailer's invitation to have a drink, Pynchon replied with a note saying simply, "No, thanks, I only drink Ovaltine." After the Pulitzer committee refused to accept the recommendation of its literary panel that the novel considered by many to be Pynchon's best, Gravity's Rainbow (1973), be awarded the Pulitzer Prize (the committee called it "unreadable" and "obscene"), the book was awarded the National Book Award and the Howells Medal. To the National Book Award ceremony, Pynchon's publisher sent Professor Irwin Corey, a frizzy-haired comedian specializing in ridiculous double-talk, in Pynchon's place; meanwhile, Pynchon tried unsuccessfully to decline the Howells Medal, writing "The Howells Medal is a great honor, and, being gold, probably a good hedge against inflation too. But I don't want it. Please don't impose on me something I don't want."

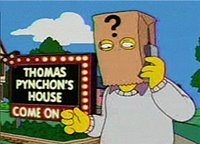

After 17 years, Pynchon published two new novels in the 1990s: Vineland (1990) and Mason & Dixon (1997). In 2004, Pynchon broke his "silence" by "appearing" on Matt Groening's long-running animated sitcom The Simpsons as himself, lending his friendly, unmistakably Long-Island-accented voice to the soundtrack and permitting himself to be drawn with a paper bag over his head standing out in front of his well-indicated home, offering his autograph to passersby. Just imagine J.D. Salinger doing anything of the sort.

Labels: Books, Literature

3 Comments:

I enjoyed The Crying of Lot 42 best. There is a Polish writer whose encyclopedic and labyrinthine way of writing Pynchon reminds me of. The difference is that Pynchon feels American to me -- he has no sense of high and low, it is all a potpourri of everything, while Parnicki is really impossibly high culture. you can guess who is my favorite author?

(I will have to give Parnicki a try.) I read Crying of Lot 49 when I was 16 and have been hooked on Pynchon ever since. As I've suggested in other communiques, I quite like the potpourri of high and low -- being American and all, I pretend to notice the similarities more than the differences . . .

I dont think any Parnicki is translated. Unless I get up to it. It would be one hell of a job, I tell you.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home