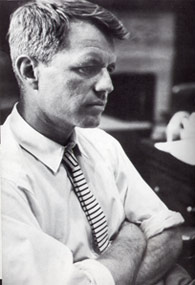

Bobby

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of the birth of Robert F. Kennedy, better known to the world as "Bobby," the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Human Rights held a panel discussion last Wednesday (with such leading lights as United Farm Workers leader Dolores Huerta, New Orleans ACORN's Stephen Bradberry, and Indian Dalit rights activist Martin Macwan) on the relevance of Bobby Kennedy's vision today. Such exercises are all very nice and appropriate, but if he were alive today, one might expect that Bobby Kennedy would have passed. Near the end of his life he seemed, more than any other American politician of his day, to stand for the proposition that talk is cheap.

The third son of Joseph Kennedy and younger brother of President John Kennedy, Bobby Kennedy was perhaps the most complex member of the Kennedy family -- a moody creature of instinct whose internal demons and experiential sensitivities drew him to articulate a moral critique of American poverty and human rights issues unlike any mainstream American politician of his time. Few people would deny that had he not died in 1968, the American political landscape in the latter half of the 20th century would have looked very different.

While he was still young, Bobby's father was named Ambassador to Great Britain by Franklin Roosevelt, so Bobby moved to England with the rest of the family, attending a fine British prep school and parties with Princess (future Queen) Elizabeth. He followed his brothers into the Navy and Harvard, although he saw no action in the Navy and was not known to be a good student (despite his slight build, his bulldog determination earned him a spot on the Harvard football team, and a varsity letter -- something his older brothers never achieved). After reporting on the Middle East for the Boston Globe, he attended law school at the University of Virginia.

Following law school he stinted with various U.S. government jobs, worked on brother John's political campaigns, and toured Central Asia with Supreme Court justice William O. Douglas, and became counsel to the Senate subcommittee on investigations, first under Joe McCarthy and later under John McClellan. McCarthy was a family friend, and initially Kennedy supported his investigation of alleged communist infiltration of the State Department, but had parted company with McCarthy and his unprincipled accusations in 1953.

Kennedy later emerged as chief counsel to the McClellan's select committee on improper activities in the labor and management field. Kennedy gained notoriety as the Senate's chief interrogator of labor racketeers (ironically, using some of the same cross-examination techniques for which McCarthy was criticized), doggedly pursuing the illegal activities of Teamsters boss Jimmy Hoffa and eventually landing Hoffa in prison for jury tampering.

In 1956, Kennedy unsuccessfully led the effort to have his brother John nominated as Adlai Stevenson's vice-presidential running mate, and was one of his brother's chief advisors in John's successful 1960 presidential campaign. Rather unexpectedly, President John Kennedy nominated his 35-year old brother Bobby as Attorney General over Bobby's objections -- a choice decried by many as unadulterated nepotism. Nevertheless, Kennedy distinguished himself as John Kennedy's closest advisor (some referred to Bobby as the "assistant president"), and as the administration's highest-placed advocate for African-American civil rights.

Following the assassination of his brother John in 1963, Bobby stayed on as Attorney General in Lyndon Johnson's administration for a time, but felt increasingly alienated and resigned to run for U.S. Senate from New York with Johnson's blessing. Despite charges that he was using New York and the Senate as a stepping stone for his own political career, Kennedy campaigned hard: with a longish mop of hair, an easy smile and a sense of humor and charisma all of which reminded the public of his late brother, Kennedy was mobbed at every stop, and despite the opposition of New York liberals such as Gore Vidal and James Baldwin, Kennedy won handily in November 1964. Still mourning John's death, he scaled Mt. Kennedy, a 13,900-foot Canadian peak named in honor of his brother, in the spring of 1965. While he found the climb arduous, he did it well (he noted that while he didn't like climbing mountains, he liked hanging around with guys who climbed mountains), and it seemed to pick up his spirits, as well as to reveal something of what fueled Kennedy.

Kennedy's desire for the first-hand, tactile experience became a theme in his political life for the last years of his life. After experiences among the shanties of South Africa and in the Mississippi delta, Kennedy visited the impoverished neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesent hoping to do something about poverty within New York. At first, he met with distrust among the largely African-American community, but eventually Bobby won them over. Few politicians in that day bothered to visit such blighted areas to listen to the disenfranchised inhabitants, but Robert Kennedy was part rebel, bucking the established patterns of public service and part missionary, having long before accepted his role as the privileged son of wealth honoring his obligation to minister to those less fortunate. He succeeded in establishing a cooperative project between Bedford-Stuyvesent residents and business which became a model for addressing inner-city poverty within the U.S.

As the Vietnam War escalated during the Johnson administration, Kennedy began to admit to himself the mistakes he and his brother had made with respect to Vietnam policy, and eventually made a violent public break with Johnson and his own past by coming out against further American involvement in the War. After Senator Eugene McCarthy made a surprisingly strong showing against Johnson in the 1968 New Hampshire presidential primary as an anti-War candidate, Kennedy saw that Johnson's re-election was not a foregone conclusion, and within a month declared his own candidacy.

Thoroughly unprepared for a national campaign, Kennedy got off to a somewhat shaky start, but on his way into the California primary in June, he seemed to have momentum. By the late evening of June 4, Kennedy held a 3 percent lead over McCarthy and Vice President Hubert Humphrey, taking 174 delegates and putting him within striking distance of the Democratic nomination. Moments after his victory speech at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, Kennedy was shot to death by Sirhan Sirhan -- only two months after the assassination of civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr.

Bobby Kennedy's assassination was possibly my earliest TV news memory -- apart from the daily barrage of Vietnam footage we could all expect at dinner time, and which even as a young child, I was beginning to take for granted. I was, however, just beginning to understand that the world was a big place. That jagged silence cutting through the middle of a night of regular broadcast television, followed by the somber intontations of the "breaking news" announcer, declaring that this man had been shot -- well, it was a terrifying thing for a little boy, but also an instantly maturational object lesson concerning the times in which we lived.

Bobby Kennedy was mourned deeply, in some ways even more deeply than his brother John, by American youths older than me at the time, who were mobilized by his fresh perspectives, and by the disenfranchised poor and African-Americans for whom he had battled . . . leading many to wonder what might have been.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home