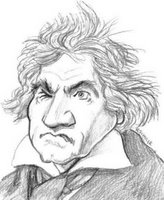

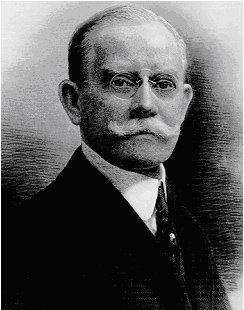

Listeners of the 19th century crowned Beethoven as the greatest of all composers and proceeded to carve his name in marble on the fronts of concert halls from Sacramento to Eger. Partly in backlash, partly as a result of the rediscovery of the mastery of Bach and

Mozart and the post-modern unwillingness to cast assessments of singular pre-eminence in any kind of stone, Beethoven has been cut down to human size and is no longer as often referred to as "the greatest"; in fact, the 20th/21st century preoccupation with personality has often led us to choose to dwell on his very human, very personal circumstances -- his volatile temperament, his failures in love, and his deafness, each played out somewhat grotesquely in the film

Immortal Beloved, 1994, starring Gary Oldman.

The result is that it is almost impossible to give a fresh listening to his music today; nevertheless, its passion continues to draw us in, as Beethoven is still probably the most often performed composer in concert halls around the world.

Born or baptized on this day in 1770 (the sources waffle on the point), the son of a drunken tenor at the court of Bonn -- Ludwig Van Beethoven showed moderate musical talent as a child. His father wanted to make him into a lucrative child star; instead, Beethoven's development as a musician was deliberate, fostered by local musicians with whom he performed in the Bonn Orchestra until he was 17, when during a visit to Vienna he performed for Mozart, who was enthusiastic about Beethoven's talents as an improviser.

When he returned to Vienna in 1792 (shortly after Mozart's death) to study with Joseph Haydn, he was instructed by an old family friend to "receive the spirit of Mozart from the hands of Haydn"; but Beethoven, at that time, was already showing the stubborn independence of mind and spirit which has inevitably shown through in his finest compositions (and destroyed most of his personal relationships, incidentally), shrugging off Haydn and sneaking lessons with Salieri and Albrechtsberger, among others, whom he also largely ignored.

Although he occasionally lived in the households of nobility, on the whole he supported himself as a hired virtuoso pianist, known for his electrifying, wildly effusive improvisations. At 30, he realized that he was losing his hearing, an absurd condition for a man who had devoted himself to music and one which increased his already disproportionate sense of isolation. He dealt with deafness (as he did with all of his maladies, emotional as well as physical, the latter of which included chronic intestinal trouble) by plunging himself into his writing -- an exercise which he undertook with temples a-bulging and teeth a-gnashing, totally unlike the apparent effortlessness of Mozart's style of creation.

Some of his earliest important compositions (Piano Concerti Nos. 1, 1795, and 2, 1794-5; the Septet, op. 20, 1799; the Symphony No. 1, 1800) were demure pieces inspired by the classicism of Mozart and Haydn which did not reveal the spirit he showed in his live performances, but he did begin to show his Romantic sensibilities in such works as the Pathetique sonata (1797-8). Although the germs of his Romanticism had been simmering in his personality all along, they were tugged through their incubation period by the cultural and political milieu of his time: Goethe and Schiller, whom Beethoven greatly admired, were bringing literary Romanticism into bloom, and the French Revolution and the rise of Napoleon (at least initially) gave hope to Beethoven's revolutionary spirit. When Beethoven finished his Symphony No. 3 (1803), he had initially given in it the name "Bonaparte," but when he discovered that

Napoleon had declared himself emperor (proving himself to be nothing more than an ordinary despot in Beethoven's eyes), Beethoven abruptly renamed the symphony

Eroica.

Eroica was a "heroic" renovation of the symphonic form: taking the logic and protocols of classicism as his starting edifice, Beethoven knocked out a few interior walls, making the "space" of the symphony larger and filling it with dramatically contrasting colors, dozens of motifs, and a weightier final movement, all in the service of a much more raw, emotionally direct and personal world (critics like to say, more "democratic") than that created by the decorous symphonies of his predecessors.

After the

Eroica, Beethoven's "worldwide" acclaim grew steadily (although at times the public greeted his newer works, which built upon the expansiveness of

Eroica, with bewilderment -- including his most famous work, the blockbusting Symphony No. 5, 1808, with its mind-numbingly famous dot-dot-dot-dash theme; his opera

Fidelio, 1805-14; and the Piano Concerto No. 5, the

Emperor, 1809) until the crowned princes of Europe paid court to him at the Congress of Vienna in 1814, at which time he unveiled his Symphony No. 7 to universal approval.

From 1814 to 1820, his public heard little from him while he busied himself with raising his nephew Karl (none-too-successfully) after the death of the boy's father. Just when everyone believed, based on the few pieces which he did release during the period (such as the unfathomable

Hammerklavier sonata, 1819), that the deaf genius had gone mad and near-silent, Beethoven began a new period of feverish productivity. His final period seems to have been Beethoven's conscious last attempt to get it right, to convey the feelings existing deeply at his core wrapped in almost unearthly layers of wisdom and acceptance; and without the aid of hearing, he conceived his works on paper in a much more elaborate fashion than their overall effect would suggest -- blotted, intensely interwoven tapestries of counterpoint, unconstrained by the old formal rules, which nevertheless leave an impression of unstudied inevitability.

The Symphony No. 9 (the

Chorale, with the final movement being a setting of Schiller's "Ode to Joy" for chorus) and the

Missa Solemnis were the transcendental capstones of the period, the translation of the personal to the universal. Beethoven himself conducted the debut performance of the two pieces in May 1824, and was unaware of the explosive applause at the end of the Symphony's finale until a member of the chorus turned him around. He was still making plans for new pieces when he hitched a ride in an uncovered milk wagon during a trip back to Vienna, caught a chill and died 3 months later.

Labels: Classical Music

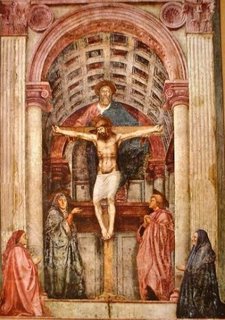

In 1425, Masaccio began his collaboration with Masolino (loosely translated as "Fat Tom") on the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel at the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, and painted the fresco which is acknowledged by many as his masterpiece, the Tribute Money. Depicting the story of a confrontation between St. Peter and a Roman tax-gatherer (as told in Matthew 17:24-27), upon which local church leaders sermonized in favor of the payment of taxes to earthly rulers to support defense, Masaccio treats the event almost as contemporary journalism, showing Christ and his disciples in the plausible light and shadows of an Arno Valley landscape.

In 1425, Masaccio began his collaboration with Masolino (loosely translated as "Fat Tom") on the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel at the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, and painted the fresco which is acknowledged by many as his masterpiece, the Tribute Money. Depicting the story of a confrontation between St. Peter and a Roman tax-gatherer (as told in Matthew 17:24-27), upon which local church leaders sermonized in favor of the payment of taxes to earthly rulers to support defense, Masaccio treats the event almost as contemporary journalism, showing Christ and his disciples in the plausible light and shadows of an Arno Valley landscape.