Brunelleschi's Dome

"In the taut curves of its profile, the force of its volume, and the dynamism of its upward leap, the shape of Brunelleschi's dome suggests the new absolute of the Early Renaissance, the idea of the indomitable individual will . . ." -- F. Hartt.

Filippo Brunelleschi, known to his contemporaries as Pippo, died in 1446 in Florence at the age of 69.

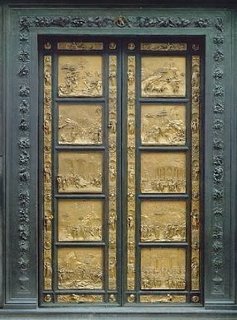

While his early rival, Lorenzo Ghiberti, would be known principally for just two works, the bronze doors on the north and east portals of the Baptistery of Florence, Filippo Brunelleschi is best known today for just one unconventional and breathtaking accomplishment, the design of the cupola for the Duomo, the Cathedral of Florence, which he worked on intrepidly with eyebrows gleefully raised high for 20 years.

Pippo's father was a member of the Cathedral design committee when Pippo was a child, so he had grown up with models and drawings of the early designs for the Cathedral. By the age of 21, however, Brunelleschi has entered the goldsmith trade, and in 1402 he was optimistic about his chances of winning the public competition being held to select a sculptor to create new bronze doors for the north portal of the Baptistery outside the Cathedral. His competition effort was well received, but in the end he placed second to Ghiberti -- and he never forgave him. After his disappointment Brunelleschi found it easy to give up sculpture for architecture, and served along with Ghiberti on the Opera del Duomo committee of 1404, doing his best to make the young sculptor look silly by exposing Ghiberti's lack of engineering expertise at every opportunity.

It is possible that the beginnings of Brunelleschi's vision began to take hold when the committee asked then-current Cathedral architect Giovanni d'Ambrogio to lower his three semi-domes. In 1407, as Vasari records, the Opera del Duomo adopted Brunelleschi's suggestion that a drum be inserted between d'Ambrogio's semi-domes and the center, thus preparing to "lift the weight off the shoulders" of the semi-domes to accommodate a massive central dome. Brunelleschi's influence on the evolution of the Cathedral's design increased in the years that followed until the Cathedral was finally declared his own project in 1420. Thereafter, the Cathedral ultimately took on the characteristics of what is often called Brunelleschi's "paper architecture," his conception of proportional architectural shapes as if on paper, elegantly partitioned and measured across the eye's plane with a geometric simplicity and order unseen in Gothic architecture.

The gigantic central dome itself, visible for miles around Florence, was literally the crown of Brunelleschi's career as a designer, a triumph of engineering as well as a stylistic statement which in some ways set the optimistic tone for the century of Renaissance artistic expression to follow. Brunelleschi solved the engineering problem of building such a large, tall dome -- the largest, tallest dome ever made until that time -- by erecting an internal dome with an exceptionally strong herringbone masonry pattern, surrounded by oak reinforcing beams held together with iron chains and fixed to stone buttresses which connected the inner shell with the outer shell.

While working on his lifetime project, Brunelleschi also managed to work on other projects, such as the Ospedale degli Innocenti (begun 1419) and the Chapter House for Santa Croce (1433), and he revolutionized the plan of church interiors with his designs for San Lorenzo (1425) and Santo Spirito (1434).

Labels: Architecture, Italy

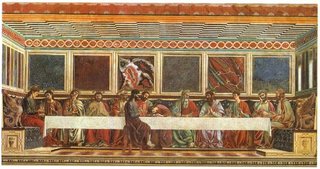

In 1425, Masaccio began his collaboration with Masolino (loosely translated as "Fat Tom") on the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel at the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, and painted the fresco which is acknowledged by many as his masterpiece, the Tribute Money. Depicting the story of a confrontation between St. Peter and a Roman tax-gatherer (as told in Matthew 17:24-27), upon which local church leaders sermonized in favor of the payment of taxes to earthly rulers to support defense, Masaccio treats the event almost as contemporary journalism, showing Christ and his disciples in the plausible light and shadows of an Arno Valley landscape.

In 1425, Masaccio began his collaboration with Masolino (loosely translated as "Fat Tom") on the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel at the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, and painted the fresco which is acknowledged by many as his masterpiece, the Tribute Money. Depicting the story of a confrontation between St. Peter and a Roman tax-gatherer (as told in Matthew 17:24-27), upon which local church leaders sermonized in favor of the payment of taxes to earthly rulers to support defense, Masaccio treats the event almost as contemporary journalism, showing Christ and his disciples in the plausible light and shadows of an Arno Valley landscape.