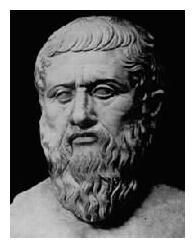

Plato

The thinker about whom Alfred North Whitehead observed that all subsequent philosophy served as a footnote was born around 427 B.C.E. into a comfortable, privileged class (his mother was a descendant of the statesman Solon), during a time when order was crumbling: 5 years before Plato's birth, Athens and its allies locked itself in a bloody war with Sparta for supremacy in the Greek world, a conflict which lasted until Plato was 23. It would not be unreasonable then to imagine that Plato's lifelong fixation on a perfect, "real" world beyond the realm of workaday sensations and perceptions was born out of a longing for the tranquility arising from just consensus and selfless abstraction.

As a teenager in Athens, Plato began to sit at the feet of Socrates. While other teachers in Athens, generally identified as "Sophists," taught young men how to be materially successful in life by instructing them in the arts of public speaking and emotional persuasion, Socrates pressed Plato and his other students to examine the roots and depths beneath the plastic surfaces of Athenian political performance and its avid marketing machinery, through the active and lively use of reason. (Think Noam Chomsky vs. Tony Robbins.) After the authorities caught on to Socrates' penetrating brand of subversion and condemned him to death in 399 B.C.E., the 29-year old Plato fled Athens for Italy (where he studied the mathematical theory of Pythagoras), Sicily and Egypt, briefly served in the military, and may have been captured, imprisoned and sold at a slave market before being freed by a sympathetic philosopher with a pocketbook.

At the age of 40, Plato returned to Athens and opened his Academy (named for its proximity to a park dedicated to the Athenian hero Academus). Stepping into the empty sandals of his late mentor Socrates, Plato became the primary teacher of a student body of both men and women (Aristotle among them), his interests focused upon philosophical inquiry, mathematics and law in the service of training young Athenians to be ethical public officials.

Plato's Dialogues, which remain among the most dramatically compelling works of philosophy ever written, give us a sense of his teaching style, stressing an exchange of ideas over book learning and placing himself within the center of the action as a fellow truth-seeker, one who had literally been through the wars. His earliest surviving dialogues (among them Protagoras, which asserts that virtue is knowledge and can be taught; and Gorgias, on ethics) are thought to be faithful representations of Socrates' thought, but the later dialogues (including Crito, on obedience to laws; Apology, a dramatization of Socrates' defense at his trial; Phaedo, the death scene of Socrates, which includes a discussion of Plato's theory of the Forms; Symposium, discussions of beauty and love; Parmenides and Sophist, further analyses of Forms) show Plato's own thought maturing.

The central metaphor which Plato uses to describe his theory of Forms is that of prisoners bound face-first against the wall of a cave, unable to move their heads to see anything but dim shadows on the wall in front of them projected by a fire behind them (a flashback, perhaps, to his own time in captivity?) -- the point being that all we are able to perceive in life is a mere shadow of an abstract, perfect reality that exists beyond perception. For Plato, concepts such as Beauty, Goodness and Love transcend their everyday usages in their abstract Forms, providing a fixed and permanent reality which may be experienced only by emerging from the cave and leaving the fickle world of perception behind.

Another of Plato's metaphors is perhaps even more instructive in understanding Plato's aims: in the Republic, Plato spins a tale about how the human soul lives in a perfect realm before it enters the human body, and that before it enters the body it must cross a dry desert before crossing the river Lethe (the river of forgetfulness); the more the soul gives in to the temptation of drinking from the river, the less of the perfection of the Forms it will remember upon entering the body. The myth perhaps reveals Plato's sense of nostalgia for an unknown time in which Justice, Goodness and Truth were uncomplicated by the layers of ego, prejudice and stratagem which existed in Athenian society after the Peloponnesian Wars, showing an awareness of how the sense of oneself in one's own body within chaotic times interferes with ethical living.

Yet in nostalgia, for Plato, there was a sense of hope. If one of the prisoners in that dim cave should escape and see the light, it would be his duty to return and lead the rest of the cave-dwellers toward perfection -- hence Plato's dedication to teaching future leaders of Athens to become "philosopher-kings," to look beyond ego, prejudice and stratagem in an effort to build a more perfect society.

Plato engaged in one experiment along these lines: at the age of 60, Plato went to Syracuse to become the tutor to the young Dionysius II, but due to what he perceived to be Dionysius' weakness of character and the treachery of Syracuse political institutions, Plato would not realize the ideal "city-state" in Syracuse. Even after the disappointment of Syracuse, Plato continued to teach young people in Athens, hoping to free a few young souls from the cave.

After Plato's death in 347 B.C.E., his Academy lived on for another 900 years in Athens, until it was closed by Justinian for its supposed pagan leanings. Interestingly enough, Plato's invitation to ascend beyond perception on an intellectual and emotional level became a point of departure for many theologians, from the Jewish philosopher Philo Judaeus to St. Augustine, in addition to countless later philosophers within the secular tradition.

Labels: Philosophy

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home