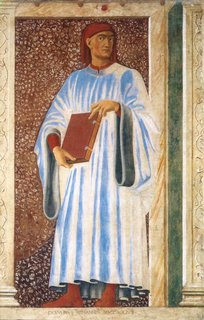

Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio, who died on this day in 1375 in Certaldo, Italy, was born to an unknown Parisian woman, the illegitmate son of a Florentine merchant who had gone to France on business. When Giovanni was 3, his father took him away from his mother to Florence, where the father soon married a Florentine who bore him another son, on whom Giovanni's stepmother doted.

From that point on, the most productive core of Giovanni Boccaccio's life and work can be explained as a series of episodes about searching for or losing feminine affection. His father sent the neglected teen to school in Naples, the playland of Italia (where it was said that no young woman who arrived as a virgin would leave as one). There Boccaccio studied business for 6 years, followed by a 6-year course in canon law.

Although wasting these 12 years on something other than developing his skills as a poet would be his lifelong regret, Boccaccio settled well into the Neapolitan social scene, eventually becoming the lover of Maria D'Aquino, the illegitimate daughter of King Robert. Maria would become his Beatrice and his Laura, styled in his writings as his "Fiammetta" ("flame") -- although it should be said that while he admired the work of Dante and Petrarch and their chaste devotion to their muses, unlike his courtly heroes Boccaccio had actually embraced his muse in the flesh, and thus his passions could not help but be expressed more earthily.

With Maria as his inspiration, Boccaccio wrote a string of somewhat mediocre romances drawing upon earlier sources: Filocolo (1336-8, on the ancient love story of Floire and Blanchefleur), Filostrato (1339, with the Trojan War as his setting) and Teseida (1339-41, the first Tuscan epic poem). While spotty, they were popular, becoming the inspiration for several of Chaucer's works.

Maria soon grew tired of Boccaccio and dumped him, and shortly thereafter he was recalled to comparatively austere Florence by his overstressed, financially strapped father. He wrote 2 stilted moral allegories before finding his footing with Fiammetta (1343), in which he reversed the roles of himself and Maria D'Aquino, relating the story of the agony of a woman abandoned by her lover.

To support himself, Boccaccio accepted several diplomatic posts on behalf of the Florentine government while writing his masterpiece, the Decameron (c. 1348-53), about 10 fashionable young people (the late Medieval versions of OC kids, no doubt) who flee Florence during the Black Plague to a country villa and tell each other tales to pass the hours -- 100 rich, colorful, sometimes bawdy stories about clever women and clumsy men, the pious and the depraved, the king and the beggar -- through which Boccaccio showed his virtuosity in shading different voices, passions and moods.

Although Boccaccio was somewhat dismissive of the work (a first edition was not printed until near the end of his life), later generations mined it deeply as it became a compelling source of theme and story for Chaucer (again), Shakespeare and Dryden, among others. Impoverished at 37, Boccaccio met the great Petrarch, who invited him to join his household for a time as a kind of literary junior partner. The influence of Petrarch and his own receding faculties as a womanizer turned him away from Italian vernacular (except for one last vicious swipe at the fickle character of women in Corbaccio, 1354-55) toward writing scholarly works in Latin. For a time he supported in his household a rather disagreeable Greek scholar who made, at Boccaccio's request, the first translation of Homer into Latin.

From about 1360, Boccaccio entered the clergy and assumed a most austere lifestyle; only Petrarch convinced him not to burn his writings and his library. His final literary gesture was his delivery of a series of public lectures in Florence about Dante's Divine Comedy.

Labels: Italy, Literature

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home