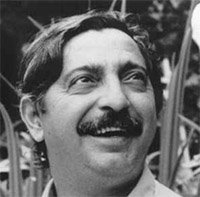

Chico Mendes

"My dream is to see this entire forest conserved because we know that it can guarantee the future of all the people who live in it . . . If a messenger from the sky came down and guaranteed me that my death would help to strengthen our struggle it would even be worth it. Experience teaches us the contrary. I want to live." -- Chico Mendes, 1988.

The man whose life stands almost as a symbol of the fight to preserve the Amazon rainforest actually began his struggle as a way of preserving the economy in which he grew up. The Amazon rainforest is the world’s largest and most ecologically diverse forest on the planet, a mystical sanctuary for ecologists around the world. When Chico Mendes (born on this day in 1944 near Xapuri, Acre, Brazil) was a child, however, the forest had been his family’s livelihood for generations -- not for lumber to be harvested there, but for the latex to be tapped from its living Hevea trees.

Mendes was a rubber tapper from the age of 9 and never had a formal education, but he learned to read from a local left-wing revolutionary and absorbed world political news from the Voice of America, Radio Moscow and BBC World Service. During the 1960s, public homesteading laws in Brazil made it possible for wealthy ranchers to move into the far reaches of the isolated state of Acre where Mendes plied his trade and indiscriminately clear out trees for cattle grazing; while by the 1980s only 130 ranchers controlled lands in Acre, their activities (both their poaching and their violent strong-arming) has led to the displacement of over 100,000 rubber tappers and their families.

In the 1970s Mendes became a member of the Catholic church-supported Confederation of Agricultural Workers, through which he and his mentor Wilson Pinheiro began to set up human blockades, long lines of rubber tappers and their families, to literally place their bodies between the loggers’ chainsaws and the trees. These nonviolent protests had limited success but did serve to attract attention to the plight of the rubber tappers. The ranchers responded violently, however, using local police to threaten, torture and kill many rubber tappers, and eventually murdering Pinheiro in 1980.

After the murder of Pinheiro, Mendes assumed the leadership of the rubber tappers’ movement, and through the First National Rubber Tappers’ Congress, Mendes was able to get enough support to convince the Brazilian government to establish "extractive reserves" in which only renewable resources, such as latex and Brazil nuts, could be harvested. This attracted the attention of the international environmental community, which assisted him in successful lobbying efforts in Miami and Washington, D.C. to stop the Inter-American Development Bank from funding a major road into the forest which had been promoted by cattle ranchers. Mendes had not initially thought of his struggle as an environmental struggle, but a political and economic one; nevertheless, he loved his homeland and recognized the power of the ecological arguments for the preservation of his ancestral land, and embraced the international movement with heart and mind.

In 1987, Mendes was awarded the UN Global 500 Prize and a medal from Ted Turner’s Society for a Better World, but the local ranchers and corrupt police in Acre did not care about Mendes’ international accolades. To them, he was a pariah, and on May 24, 1988, Mendes received his official, anonymous notice that he would be killed, a ritual among the strongmen in western Brazil. Despite warnings to the local federal police, who turned a deaf ear, Mendes was murdered 7 days after his 44th birthday with a shotgun blast to the chest while on his way to take a shower in his backyard bathhouse.

Mendes’ death made the front page of the New York Times, and within 48 hours the international press had descended on tiny Xapuri, leading an embarrassed Brazilian government to move in with a small army and arrest Darci Alves Pereira for the murder. Although there had only been 8 convictions in connection with the over 1,500 rubber tapper murders between 1964 and 1989, Pereira and Pereira’s father Darly, a notorious ranch strongman, were convicted of Mendes' assassination, although Darly’s conviction was overturned for lack of evidence in 1992. It is surmised that forces connected with the ranchers' newspaper, O Rio Branco, participated in the conspiracy behind Mendes’ death.

While at least 21 "extractive reserves" comprising 8.2 million acres have been set aside in Brazil as a result of Mendes’ efforts, they only represent about 1.5% of the Brazilian Amazon, and deforestation continues at staggering rates into the 21st century.

[A cinema note: John Frankenheimer made a film about Mendes, The Burning Season (1994), starring Raul Julia.]

Labels: Conservation

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home