Antonello da Messina

The painter Antonella da Messina died on this day in 1479 in his hometown of Messina, Italy at about the age of 49.

Despite having spent only a year and a half in Venice (1475/6), Antonello da Messina is considered to be the most influential painter in Venice of the 15th century, urging Giovanni Bellini toward his great mature works. Vasari said he was the first Italian to paint in oils, a claim which has been disproven, but nonetheless he was a pioneer of the medium.

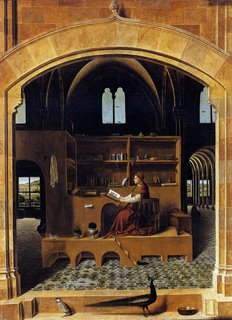

The son of a Sicilian stonecutter, it is supposed that he received his early training from a minor Flemish-influenced painter in Naples (where he probably first saw the work of Jan Van Eyck), and that in his 20s he worked alongside Petrus Christus, Van Eyck's pupil, in Milan. His affinity with the Flemish style made his work startlingly different from the work of contemporary Italian painters, with its quiet absorption of living details bathed in bright daylight and shadows. His St. Jerome in His Study (see below, 1450-55; National Gallery, London) is an inquiry into the saint's interior life through an exploration of the ordinary artifacts of his scholarly chambers, with the lion lurking in the shadows on the majolica floor representing the palpable reminder of St. Jerome's desert hermitage.

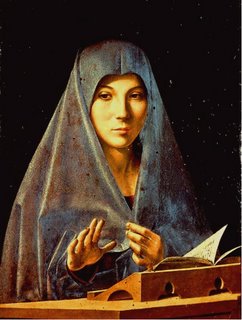

Interior life is central to his magnificent portraits, including his masterpiece Virgin Annunciate (above, c. 1465; Museo Nazionale, Palermo). Shown in three-quarter view in the Flemish manner which Antonello helped to popularize in Italy, the Sicilian-featured Virgin pauses gravely in the shadow of her blue veil, marking the text of Isaiah with the weight of one hand while the other is raised gently, marking her acceptance of her fate as much as her surprise in receiving the message. As with the portraits of Van Eyck, the background is dark, emphasizing the luminescence of the veil and her knowing face. Here Antonello manages to combine the best of both Flemish and Italian traditions -- the eye for household detail and the weight and grandeur of his subject -- in a work which transcended both, pointing (as the ever-perceptive Frederick Hartt observes) to the next century and the innovations of Caravaggio.

A glowing Portrait of a Man (c. 1465; National Gallery, London), placed in the same dark background, is sometimes thought to be a self-portrait. His Crucifixion (National Gallery, London) and St. Sebastian (Gemaldegalerie, Dresden) date from his Venetian visit, after which he returned to his workshop in the relative obscurity of Messina.

Labels: Italy, Painting and Sculpture

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home