Ugly Tom

"Giotto born again, starting where death had cut short his advance, instantly making his own all that had been gained during his absence, and profiting by the new conditions, the new demands -- imagine such an avatar, and you will understand Masaccio." -- B. Berenson.

Masaccio, a giant in the history of Western art, was born Maso di ser Giovanni on this day in 1401 at Castel San Giovanni di Altura.

Although he was not known to have shown particular artistic talent as a youth and was not associated with any great teacher of painting, Masaccio (loosely translated as "Ugly Tom") managed to enter the Florentine guild of painters, the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, at the age of 20, having demonstrated his full competence as a painter. Rather than look to other painters as mentors, however, Masaccio studied the works of the sculptor Donatello and the architect Filippo Brunelleschi, two artists who, as successors to Giotto, had fully embraced classical antecedents and instilled them with the life and spirit of their age.

In his first known work, the San Giovenale Triptych (1422), Masaccio followed the example of his mentors by shunning the decorous and other-worldly International Gothic style which still pervaded Florentine painting of that era: his saints exist in real daylight, have human weight, they are visibly uncomfortable and display grim faces; the Christ child is a chubby, awkward baby sticking two fingers in his mouth.

Most importantly, however, like Giotto, Masaccio wanted to demonstrate dramatically that intellectual distinction and learning were essential aspects of the great painter -- pictorial symbols abound in the Triptych, such as the grapes of the Eucharist in the child's hand and the stiffness of the child foretelling the scene of the Pieta.

In 1425, Masaccio began his collaboration with Masolino (loosely translated as "Fat Tom") on the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel at the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, and painted the fresco which is acknowledged by many as his masterpiece, the Tribute Money. Depicting the story of a confrontation between St. Peter and a Roman tax-gatherer (as told in Matthew 17:24-27), upon which local church leaders sermonized in favor of the payment of taxes to earthly rulers to support defense, Masaccio treats the event almost as contemporary journalism, showing Christ and his disciples in the plausible light and shadows of an Arno Valley landscape.

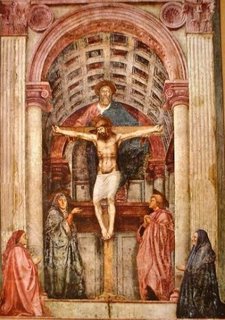

In 1425, Masaccio began his collaboration with Masolino (loosely translated as "Fat Tom") on the frescoes of the Brancacci Chapel at the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine, and painted the fresco which is acknowledged by many as his masterpiece, the Tribute Money. Depicting the story of a confrontation between St. Peter and a Roman tax-gatherer (as told in Matthew 17:24-27), upon which local church leaders sermonized in favor of the payment of taxes to earthly rulers to support defense, Masaccio treats the event almost as contemporary journalism, showing Christ and his disciples in the plausible light and shadows of an Arno Valley landscape.His Crucifixion (1426) showed a sophisticated understanding of the use of perspective, and is specifically designed to be seen from a low point of view, as was his final known work, Trinity (1427-8; fresco at Santa Maria Novella in Florence). In Trinity, we see the unity of all that was great in Masaccio's work: the sculptural reality of the figures, portrayed in an elaborate architectural setting with a keen sense of the tricks of perspective in realization of the theories of Brunelleschi; and the dramatic, literary character of the scenario, imbued with mysterious yet evocative visual references to past and present.

He died an untimely death at the age of 26, cause unknown, leaving behind an astounding body of work for a man his age which can only be explained by a combination of uncommon drive and vision.

Labels: Italy, Painting and Sculpture

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home