California Wine

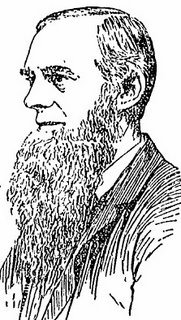

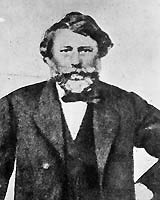

Pioneer California vintner Agoston Harazsthy de Mokcsa was born on this day in 1812 in Futtak, Hungary.

Harazsthy was an international wheeler-dealer long before it was fashionable -- a man of European charm, connections and some obvious talent who took risks and found occasional success, but also encountered his share of suspicion and bad luck. The son of a Hungarian general whose family had grown wine grapes for generations, Harazsthy became a member of Emperor Ferdinand I's guard unit at 18, and rose through the ranks of Hungarian nobility by the time he was 25, serving as private secretary to Archduke Joseph and as a delegate to the Diet. He became involved with the revolutionary movement of Louis Kossuth; but after Kossuth's arrest in 1837, Harazsthy was ostracized and forced to emigrate to the U.S.

He did so with a flourish, arriving in Washington, D.C. and introducing himself in his full dress Hungarian guard uniform to the likes of President Tyler and Daniel Webster. Through the intercession of Lewis Cass he managed to sell his Hungarian estate, move his family to the U.S., and stake his stead in Sauk City, Wisconsin (which he called Szeptaj, or "beautiful view"), where he opened a brickyard, established an emigrants' aid association, grew wheat and corn and attempted to start a vineyard. The climate proved too harsh for wine grapes, and poor harvests led him to start over on a wagon train to California, but not before the Wisconsin legislature honored him with a state dinner.

He arrived in San Diego by the end of 1849 and, self-styled as "Count Harazsthy," he became the first sheriff of San Diego County. He was noted for cleaning up the rough seaport and quashing violent Indian protests over his attempted enforcement of taxes at Agua Caliente, although he was charged with a conflict of interest in the building of the jail. He stepped down and was elected to the state legislature, where he argued for the separation of California into north and south states.

Still determined to grow good wine, however, he left San Diego for San Francisco, where Franklin Pierce appointed him assayer to the U.S. Mint in 1857. He bought land at Sonoma that year, and while he succesfully fought a charge of embezzlement which forced him to resign from the Mint, he began to introduce European varieties of grapes to replace the lackluster Mission vines -- the first Zinfandel, Tokay and Muscat of Alexandria grown in California -- flouting tradition by planting the vines on dry, thinly-soiled hillsides rather than rich, flat land.

His wines soon gained a reputation, winning the medals at the state fairs in 1858 and 1859, and in effect launching the California wine industry. In 1859, he wrote the first monograph on California wine, which prompted the California legislature to appoint him to a committee to report on improving winegrowing in California. Believing he had the legislature's blessing, Harazsthy financed his own trip to Europe, where he purchased $10,000 worth of prime grapevines and cuttings, as well as olive, pomegranate, lemon and orange cuttings for growing in California. He returned to California and published a popular and influential book, Grape Culture, Wines and Wine-Making (1862), half travelogue and half agricultural manual; but the legislature, mistaking his Democratic politics for support of the Confederacy, withheld reimbursement for his trip. A venture capitalist named Ralston came along to bail him out, but Ralston became frustrated with Harazsthy's slow, deliberate techniques and maneuvered Harazsthy out of the vineyard by 1866.

He decided to start over once again, this time with a sugar plantation in Nicaragua, but after just 2 years he drowned, on July 6, 1869, near Corinto while trying to cross a river on his mule. By 1880, much of the grapes Harazsthy had planted were destroyed by root blight, but not before heartier cuttings were returned to Europe to save European vineyards from another plague of root blight.

In 1989, Harazsthy's Sonoma home was rebuilt and turned into a state park.

Labels: Wine