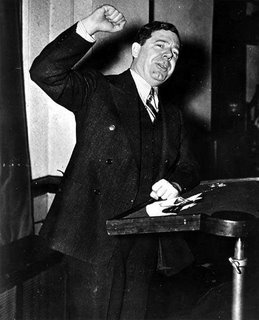

The Kingfish

Charismatic and brash, Huey Long and his loudly broadcast populist rhetoric were viewed by many American leaders of the day as threats to the principles of private property. At home in Louisiana he was vilified by the landed gentry, who saw him as an ambitious, corrupt demagogue, and virtually worshipped by the Louisiana poor who heralded him as their champion, a modern day Robin Hood. In truth, he was a good bit both, but wherever one stood one had to admit that he was an exceptionally gifted politician, a seducer of sympathies probably unmatched in the 20th century until the rise of another Southern governor, Bill Clinton.

He was born on this day in 1893 in Winn Parish, Louisiana. Starting his career as a traveling salesman, Long patched together an education in the law and began to practice in 1915 with the conscious goal of entering politics. In 1918, he led a well-publicized defense of Socialist state senator S.J. Harper against a trumped up violation of the federal Espionage Act, and later that year parlayed his notoriety into a seat on the Louisiana Railroad Commission. For 8 years, Long honed his characteristic down-home style and stole headlines with a righteous rant against big oil companies and utilities.

He lost the 1924 governor’s race, but battled back to win the statehouse in 1928, with decisive leads in the rural parishes to overcome his weak showing in New Orleans. As governor, Long plowed money into new roads, bridges, hospitals and schools, and modestly shifted tax burdens away from the middle class to corporations and the wealthy. In the process of directing reform, Long masterfully consolidated his personal power, constructing an impenetrable statewide machine through shameless political patronage and building an enormous, under-the-table pool of political mad-money by appropriating a portion of the salaries of all public employees.

Even Long’s supporters admitted that Long had assumed the powers of a dictator, calling him the "Kingfish" (a name taken from a character, played by Freeman Gosden, on the Amos n’ Andy radio show). In 1930, Long won election to the U.S. Senate, but continued to serve as governor until 1932, when he secured the succession of a docile, lap-dog crony.

As a critic of the Hoover administration, Long campaigned actively for Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, but Long soon broke with Roosevelt over his lack of a strong commitment to redistributing American wealth along equitable lines. Long opposed New Deal legislation with fiery filibusters, and announced his own economic program, known as the "Share the Wealth Plan," calling for higher income taxes; liquidation of all fortunes in excess of $3 million; a $1 million limit on personal income; granting federal "homesteads" of $5,000; and an annual federal income subsidy of $2,500 -- all in the service of taking from the rich and giving to the poor.

Through national radio addresses, 2 "autobiographies" (Every Man a King and My First Days in the White House, both 1935) and a ceaseless public appearance tour, Long established the beginnings of a national populist movement which was widely seen as a potential springboard for a 1936 or 1940 presidential candidacy. As his popularity soared, he also showed his vulnerability: a man of Ruthian appetites, he could embarrass himself handsomely in public. During one notorious drunken revel, he pissed on the trouser leg of a blue-nosed country clubber on Long Island; yet he somehow overcame such embarrassments armed with his extraordinary personal charm.

His popularity and his vocal opposition to what he described as the tyranny of New Deal bureaucracy led Roosevelt privately to refer to Long as one of the "2 most dangerous men in America" (the other being Douglas MacArthur). While Long survived an impeachment attempt in 1929, as well as IRS and FBI investigations ordered by Roosevelt, he would not survive the visceral ire of the New Orleans elite in his own backyard. Just as his national movement began to reach a fever pitch, Long was fatally shot on September 10, 1935 in the Louisiana capitol building by a New Orleans physician, Carl Weiss, who apparently had an obsessive hatred of Long not uncommon among his social set.

Although Long’s "Share the Wealth" movement, temporarily prolonged by political allies such as Father Coughlin, Dr. Francis Townsend and Rev. Gerald L.K. Smith, collapsed without Long’s personal magnetism to support it, his political legacy lived on in Louisiana. His wacky brother Earl served as governor and his son Russell was a U.S. senator; and surely the improbable successes of Edwin Edwards and David Duke, among others, find their model to some degree in Huey Long’s career.

Robert Penn Warren’s Pulitzer prize-winning novel All the King’s Men (1946) was a fictionalization of Long’s rise and fall. Despite all the warts, Long was cited as one of "10 Outstanding Governors of the 20th Century" (Weeks, Harvard Institute of Politics, 1981).

Labels: American Politicians

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home