Mark Rylance and Shakespeare's 'Measure for Measure'

Among Shakespeare’s plays, Measure for Measure (first performed in 1604) has never been one of my favorites. Apparently, I’ve not been alone in my assessment. As the venerable G.B. Harrison observed:

Measure for Measure is one of Shakespeare’s unpleasant plays, and has, on the whole, been roughly treated by the earlier critics . . . It is not surprising that critics should disagree, for the play presents a stark problem of human conduct: When a woman is offered the choice of saving a condemned man – her brother, as it happens – at the cost of her own chastity, what should she do? As Shakespeare states the problem there is no simple answer . . .Harrison is certainly correct that Measure for Measure is a “plots-and-stratagems” play. Vincentio, the Duke of Vienna, tells his confidantes that he is traveling to Poland, and he appoints his conscientious follower, Angelo, as his deputy, with the full power to condemn the guilty to death. A young gentleman named Claudio, who has secretly become betrothed to Juliet, is arrested on the accusation of having sired Juliet’s unborn child out of wedlock; and Angelo, with a great show of self-righteousness, condemns Claudio to death. Claudio’s sister, the equally self-righteous Isabella (who is studying to become a nun) pleads with Angelo for mercy, but, as Harrison says, “suddenly the old restraint snaps,” and Angelo offers Isabella a non-negotiable proposition for her brother’s release – that Isabella must give Angelo her chastity in exchange for Claudio’s life. Meanwhile, the Duke has taken on the guise of a lowly friar, who advises Isabella to consent to the bargain, only to pull a switch and substitute Mariana, a woman to whom Angelo was once betrothed but whose dowry was lost at sea, as his bed-mate. Angelo satisfies his lust without the trick being revealed (somehow), but when pushed to honor his end of the bargain, he refuses to release Claudio, calling for his head. The Duke tries to fool Angelo with the head of a substitute condemnee; luckily for the Duke, another prisoner’s head becomes available unexpectedly, and in the ensuing “reveals,” Angelo is ordered to marry Mariana, Claudio is reunited with his Juliet, and the Duke asks Isabella to marry him – an ending, says Harrison, that is “more symmetrical than convincing.”

Few of Shakespeare’s comedies could possibly have happened in real life, but usually no one takes the stories too seriously, because they never touch the deeper levels of emotion. This play in its earlier and middle scenes has been too powerful. Emotions have been so painfully stirred by the central problem that the critical instincts demand an answer. A profound moral issue has been stated, and we are not to be satisfied by a series of plots and stratagems, no matter how ingenious . . . He treated his puppets seriously, and he made them human, with the result that the soul of the play became too great for its body.

It probably says something about me that, on the evening of Pittsburgh’s worst blizzard of December 2005, I decided I needed to see Mark Rylance and his traveling Shakespeare’s Globe troupe perform Measure for Measure at the O’Reilly Theatre on December 7. On the way in, Pittsburgh’s streets were still clear of snow and I still agreed with Harrison that Measure for Measure was one of Shakespeare’s unpleasant plays; but after seeing Rylance’s production, whistling as I gingerly passed to the right of fish-tailing 18-wheelers on snow-clogged Route 22 East, I had a different view.

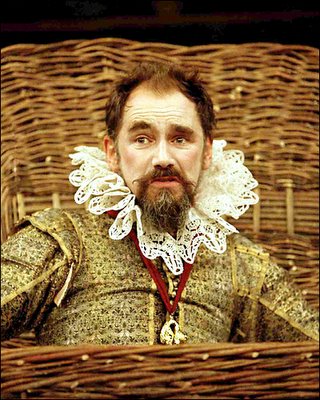

In his farewell tour as artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre in London, Rylance took a gamble, at least from the box office point of view, that he’s been known to take in the past by presenting Measure for Measure in accordance with “original practices.” For today’s attention-deficit-disordered consumers of entertainment, saying that something is being presented in accordance with “original practices” is akin to telling us that this week’s episode of Desperate Housewives will be broadcast in black-and-white, with no dialogue track, accompanied only by Gaylord Carter on the organ – we expect a maddeningly primitive and stilted presentation.

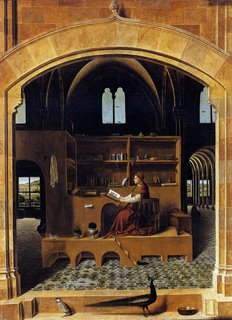

“Original practices,” when it comes to playing Shakespeare, actually means that a play is presented on a bare stage, with handmade period costumes and period music, and most significantly, with an all-male cast – yes, that’s right, men playing women’s roles.

Instead of yielding a maddeningly primitive and stilted production of Measure for Measure, Rylance’s “original practices” actually has the effect of enlivening a moribund play – giving a neglected manuscript the chance to be understood through the lens of contemporary social relations.

For starters, Rylance encourages a certain level of interaction between his cast and the audience, fostering the kind of winking intimacy that one imagines must have been present when Shakespeare originally staged his productions, in a smaller London, amid the camaraderie of local playgivers and local playgoers. Lucio is allowed to ask a question of the audience and wait for it to answer him; the Duke is permitted to acknowledge the audience’s laughter over a bit of business; and an audience member may be pulled onto the stage at the conclusion of the piece, to help perform the closing dance number. Rylance apparently loves this stuff: legend has it that while playing Hamlet, after a woman in the audience spontaneously answered Rylance’s “to be or not to be” with a “that is the question” rejoinder, Rylance turned and pointed to the woman and declared, “Indeed, madam – that is the question.”

The darker passages of Measure for Measure are largely unspoiled by this freewheeling interaction. In fact, Harrison’s concern about the juxtaposition of comedic contrivances and deeper emotions is mitigated here in the post-M*A*S*H era, in which we have grown accustomed to the “dramedy” template, and in which our favorite “puppets” are allowed to experience deep turmoil.

More to the point, however, is the way in which Rylance’s deployment of “original practices” has the effect of emphasizing the things about Measure for Measure that connect with modern audiences. G.B. Harrison says, writing in 1948, that the play raises a question about the value of chastity. We’d put it another way today – we’d say that the play concerns itself with the sexual harassment of women, raising uncomfortable questions about power structures that pit women petitioners against those would prey on them. This aspect of the play is actually heightened by the fact that men are playing women in Rylance’s production. Imagine if, in your next human resources workshop, male mid-managers are asked to play female assistants in a role-playing exercise, and perhaps you can begin to understand what I mean by this. In having men play out scenes of sexual harassment, the play presents itself almost as a kind of ritualized catharsis, a mimetic acceptance of personal responsibility that in itself is quite powerful to behold.

The all-male cast also has the effect of universalizing the central concern of the play: the ways in which the administration of justice, arbitrary and often cruel, rubs up against the inviolability of human individuality and choice – the sovereign government against the sovereign me. In context, Shakespeare can perhaps be forgiven if he fails to answer questions in Measure for Measure – its first performance, after all, was before the Court of King James I, and to answer the questions would have been to call attention to uncomfortable issues of governance in the presence of He who Governed. Shakespeare here prefers to allow a benevolent observer (the Duke) and chance resolve the dramatic conflicts, and (if you'll please forgive the post-modern gloss) to leave the unanswered questions to be pondered in the silence before and after the play. That, in itself, is astonishingly subversive.

Rylance, at the helm and on the boards, swerves into Shakespeare's realm of controlled chaos. As the Duke, Rylance is “like a flustered God who's set the universe in motion and is surprised by the imperfect results,”as Timothy Gray wrote in Variety – he dithers and he hevers, with the fear of being out of control implacably written across his brow.

A friend of mine, a member of the board of the Pittsburgh Public Theater, seized upon the humility in Rylance’s performance and took the opportunity to tell Rylance that it reminded him of Peter Falk doing Columbo. Rylance thanked him and said he’d always appreciated Peter Falk’s work. Rylance offered another presumably iconic performance as his model, but unfortunately my friend doesn’t remember what the model was. (If my friend’s amnesia ever clears, I will let you know.)

As it has often been said, you have to be nuts to attempt to produce Shakespeare today, with all its layers of critical outerwear, and Rylance indeed may be certifiably nuts – he apparently is one of that dunderheaded school who believes that Bacon or one of his cronies actually authored Shakespeare’s works. Nevertheless, I hope that Mark Rylance’s swan song with Shakespeare’s Globe does not signal an end to his relationship with Shakespeare. I hope and suspect he’ll be back soon, undressing another neglected Shakespearean text to find the subversive spots and the post-modern stripes underneath.

Labels: Literature, Shakespeare, Theater