Tuesday, July 24, 2007

Wednesday, May 09, 2007

Success at Plymouth

William Bradford, Governor of the Plymouth Colony, died on this day in 1657 in Plymouth, Massachusetts at the age of about 67.

William Bradford's record of building a permanent settlement out of the virgin lands of the Massachusetts coast almost makes Walter Raleigh, John White and John Smith look like Moe, Larry and Curly. Raleigh and White misplaced a couple of groups of colonists at Roanoke between 1588 and 1590; Smith's Jamestown colony was an unmitigated disaster of Indian wars, internal mistrust and starvation which limped along until James I took it over from the brink of bankrupcty after 17 years; but within 6 short years, Bradford led the Plymouth colony in the repayment of all of its debts and the successful buy-out of its original investors amid relative peace and prosperity.

The difference may have been in their aims: while Moe, Larry and Curly came to North America in search of a quick score of gold nuggets lying on the shore, Bradford came to honor God. When he was 12 he became a member of the Separatist Church in Yorkshire, an offshoot of the Puritans, and at 19 he moved to Holland with a group of like-minded "nonconformists" in search of religious freedom. Not finding it there, he helped to organize the Mayflower voyage in which about 100 "pilgrims" sailed to the New World in 1620.

Upon arriving, he was one of the framers of the "Mayflower Compact," an agreement for voluntary civic cooperation, and as governor during almost every year from 1621 to 1656, he maintained peace treaties with Massasoit and the Wampanoag Indians; initiated such democratic institutions as town meetings and elections; helped to avoid starvation by directing the cultivation of corn; and maintained an environment of toleration for all nonconformists. He also left behind a valuable, well-written account of the colony, History of Plymouth Plantation (1620-47).

Labels: Christian History, Colonial History

Wednesday, April 25, 2007

The Pope Joan Myth

From the 13th to the 17th centuries, there was a persistent legend, told both within the Roman Catholic Church and by the Church's enemies, that a woman had once served as pope. In the most common version of the tale, a young woman from Mainz who had studied in Athens, dressed as a man, settled in Rome as a cleric and was elected pope as "John Anglicus," styled as John VIII, after the death of Leo IV in 855. Her real gender was exposed two years later, however, as she rode in a procession from St. Peter's to the Lateran, giving birth to a child (from a secret liaison with a secretary-deacon) on a narrow street between the Colosseum and S. Clemente. Enraged, Roman onlookers are said to have tied her to her horse's tale, dragged her around the city in disgrace and stoned her to death, to be succeeded by Benedict III.

Her first "biographer" was a 13th century senior scholar within the Church and later the archbishop of Gneisen, Martin Polonus, who acknowledged her existence in his otherwise dispassionate chronicle of popes, but observed that because of her fraud she was not included in the official papal registry. Subsequent writers, including Petrarch and Boccaccio, embellished the tale, but the basic facts seem to have been accepted as truth by the Church and its partisans for a few centuries -- a bust of Pope Joan had stood among the gallery of pontiffs in Siena Cathedral until 1601, and allegedly John XXI had accounted for Joan in numbering himself as the XXIst John in the papal list.

Catholic writers began to bristle at the notion of a female pope in the 16th century, but the legend was considered "demolished" by a Protestant writer, David Blondel in the 1650s. Nonetheless, modern proponents of the "Pope Joan" myth point to some unusual traditions which seem to have grown up within the Church as evidence of her existence -- including the curious pontifical election ritual practiced from the 10th to the 16th centuries in which the selected candidate was required sit in a birth-chair with a hole underneath at the time of investiture, allegedly so that a representative cardinal could inspect the candidate's gender, and the tradition that subsequent popes allegedly avoided the narrow street on which Joan supposedly gave birth. Subsequent soundings of the "Pope Joan" story include Emmanuel Royidis' novel Pope Joan (1954), a film starring Liv Ullmann (1972) and a popular Victorian card game.

Labels: Christian History, Pop Culture

Saturday, February 24, 2007

Pico's Dignity

Pico della Mirandola was born on this day in 1463 near Ferrara.

A precocious child, Pico was sent to Bologna to study canon law at the age of 14. Canon law began to sicken him, however, and he moved to Ferrara to study philosophy and theology, soon afterward meeting the philosopher Marsilio Ficino. At Padua, he gained a reputation as a public lecturer on scholarly topics, acquired a deep knowledge of Greek and the Semitic languages, and encountered ancient Greek texts by Plato and Aristotle as well as the literature of medieval Judaism. By 1484, under Ficino's influence, he was an avowed Neo-Platonist, employing Plato's methods of inquiry to a critique of the Church.

He studied in France briefly, and upon his return to Florence in 1486, he published his "900 theses" (or, Conclusiones Nongentae in Omni Genere Scientarum), a mélange of dialectics, metaphysics, theology and magic, and brashly announced that he was prepared to defend them in public debate against all the great scholars of Europe. For the impending occasion, he wrote what would become his most famous piece, the Oration on the Dignity of Man, one of the principal statements of Renaissance humanism -- stressing a return to the centrality of man in the universe.

Within a year, 13 of his theses were declared to be heresy by Innocent VIII, who forbade public discussion of the work. Pico recanted, but came back two months later with a a retort addressed to Lorenzo the Magnificent, the Apologia. In the Apologia, Pico took the extraordinary position that the Hebrew Kabbala, the Jewish mystical tradition which provided a means for approaching God directly, was the best logical basis for the belief in a divine Christ.

With Innocent still hot on his trail, Pico fled to France and was arrested there. Innocent died in 1492, and was succeeded by Alexander VI, who absolved Pico of the charge of heresy. With Alexander's blessings Pico returned to his roots in his work the Heptaplus, a mystical interpretation of the Creation. He fell away from Ficino and Lorenzo near the end of his life, when he submitted to the influence of the monk Savonarola and began a period of meditation.

He died young, on November 17, 1494 in Florence, without leaving a synthesized philosophy, but his critiques were influential: they encouraged scholars to penetrate long-ignored Hebrew texts and enriched theological discussions with an approach to mysticism derived from classical literature. His critique of astrology influenced the work of astronomer Johannes Kepler.

Labels: Christian History, Italy, Judaism, Philosophy

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Doubting Thomas

The feast of St. Thomas, one of Jesus' twelve disciples, whose feast is celebrated by some Christians on this day.

Although he is barely mentioned in the first three Gospels, Thomas is featured prominently in John's Gospel. Like the sons of thunder, John and his brother James, Thomas is a loyal fire-breather, suggesting that all of Jesus' followers accompany him to Bethany in Judea to visit Lazarus when it seemed likely that Jesus would be in danger there -- "Let us all go," he says, "that we may die with him."

Later, at the Last Supper, Thomas shows his interest in logistics when he questions Jesus about his impending departure and Jesus' promise to prepare places for his faithful followers: "Lord," he says, "we know not whither thou goest, and how can we know the way?" Jesus takes the opportunity to draw Thomas' attention beyond physical reality, telling him "I am the way, and the truth and the life. No man cometh to the Father, but by me. If you had known me, you would without doubt have known my Father also: and henceforth you shall know him, and you have seen him."

After Jesus' crucifixion, Thomas' Aristotelian drive to pull it all apart and put it all back together arises again when, being absent from the Upper Room when the resurrected Christ first appeared, he says that he won't believe Jesus had returned until he can see, with his own eyes, the holes in Jesus' hands where the nails had been, and to touch, with his own fingers, Jesus' wounds. Eight days later, when Jesus arrives and invites Thomas to "put in thy finger," Thomas is humbled, exclaiming breathlessly, "My Lord, and my God," stating more simply and directly than any of the other disciples the conclusion of his faithful questioning. Jesus, however, gently rebukes him for his habit of mind, stating that while Thomas had to see Jesus in the flesh to believe, "blessed are they that have not seen, and have believed." For this episode, Thomas is forever to be known as "Doubting Thomas," and held out as an example of imperfect faith. His namesake, Aquinas, would later provide the world with the model of the Aristotelian Christian, the faithful scientist whose faith is perfected through the exercise of logic.

Thomas is said to have led a mission to India, where he is supposed to have promised to build King Guduphara a palace which would last forever; according to legend, Guduphara gave Thomas the money to build the palace, but Thomas gave the money to the poor. When Guduphara confronted Thomas, Thomas explained (perhaps learning Jesus' lessons on metaphysics after all) that the palace he was building was in heaven, not on Earth. A Christian community on the Malabar coast of India claims its lineage to Thomas' mission, which ended when he was apparently slain with a spear while praying on a hill in Mylapur near Madras. His remains were said to have been buried there, and afterwards transported to Edessa, from which they were retrieved 800 years later and conveyed to Ortona, Italy.

The Roman Catholics name Thomas as the patron of a number of constituencies, including architects, construction workers, the blind, geometricians and theologians, as well as of India and Portugal.

Categories: Christian-History

Labels: Christian History, India

Monday, November 27, 2006

Clovis

By the time Clovis acceded to the leadership of the Franks, the Roman Empire was in a shambles: puppet emperors had been under the control of the Suevians since 456, but the Suevian power-broker Ricimer had died in 472, and the last person to hold the title of Roman emperor, the 16-year old boy Romulus Augustus, abdicated in 476. While Clovis' father Childeric still had to contend with stray Roman armies, by 481 these armies were little more than lost patrols. Clovis took the opportunity to drive the Romans out in 486, defeating (and decapitating) Syragius, the son and successor of the Roman governor of Gaul, Aegidius, and the model for the Arthurian romance Sir Sagramore the Foolish. After defeating Syragius, Clovis began to plan his conquest of the other "barbarians" along the Rhine.

He chose as his wife Clotilda, a devout Catholic and the orphaned daughter of a brother of the Burgundian king Gontebaud; Gregory of Tours later suggested that Clovis's choice of spouse was meant to unnerve Gontebaud, who had supposedly murdered Clotilda's father. In any event, Clotilda had attempted to convert the pagan Clovis at the time of their marriage, but it wasn't until Clovis found himself having trouble with the Alemanns that Clovis relented. He vowed to become a Christian if he defeated the Alemanns; and after he defeated them, he received baptism amid great pomp and circumstance from St. Remigius on Christmas Eve, 496 -- becoming the first Christian king of the Franks and enjoying the cooperation of the Church thereafter.

Conspiracy theorists suggest that Clovis' baptism was actually the consummation of a bargain struck by the Roman Catholic Church -- that in exchange for the Church's support in temporal affairs, Clovis and his progeny would renounce the Merovingian claim that the family line began with the union of Jesus Christ and Mary Magdalen. If conspiracy theories about Roswell, Marilyn, Kennedy and Elvis have got you scratching your head, imagine what motivates a modern mind to hatch a conspiracy theory focusing on the baptism of a Frankish king from the 5th century. Today's Merovingian partisans mourn the reign of the independent-minded Dagobert II (676-9) as the last true Merovingian king under the bargain, and regard the papally-supported Carolingian coup which relegated Merovingian figurehead Childeric the Lazy to a monastery in 751 as the last semi-bloody deed in the silencing of the radical Christianity of Jesus' half-brother, James the Just; on the other side of the coin, the anti-Merovingians claim that the Merovingians went underground through organizations such as the Knights Templar and are at present the unseen powers behind international industry and finance.

Clovis subsequently took on and defeated Clotilda's uncle, Gontebaud, king of the Burgundians and one of the last sponsors of the Roman emperors, in 500, and went after the Visigoths, killing Alaric II, king of the Visigoths, at Toulouse in 507 -- thereby extending the Frankish kingdom to include much of modern France and Germany. He established his court at Paris, thereby establishing the city as the preferred capital of Gaul (or France) for centuries, where he promulgated the earliest Frankish canon of written laws and meddled poorly in church affairs. According to custom, when Clovis died (on this date in 511 in Paris at the age of about 46) his kingdom was split among his four sons, two of whom (Childebert I and Chlotar I) emerged as dominant kings of the Frankish realm for a time.

Labels: Christian History, France, Kings and Queens, Pop Culture

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Malachy's Prophecies

Malachy O'Morgair, also known as St. Malachy, died on this date in 1148.

Malachy O'Morgair, also known as St. Malachy, died on this date in 1148.In his time, Malachy O'Morgair was known as an able priest and administrator who restored discipline to the lazy monks at Armagh. Afterwards he traveled through Europe, visiting Innocent II in Rome and St. Bernard in Clairvaux, in whose arms he died at the age of 54.

A subsequent tradition about Malachy is that during his visit with Innocent in 1139, he was granted a vision of each of the future popes, which he set down as a list of aphoristic prophecies about each of them, which he gave to Innocent to comfort his mind about his work. In 1590, a Benedictine monk "found" the list in the Vatican archives.

Although the work has been dismissed as a forgery perpetrated by restless Jesuits, there have been some uncanny connections between the aphorisms attributed to Malachy and some actual popes. For example, for the 84th pope after Innocent, the motto is "Sydus Olorum" or "constellation of swans," and (depending on whom you count) the corresponding pope, Clement IX, apparently occupied the chamber of swans at the time of his election. The motto for the 256th pope, "Balneo Etruria," is interesting because the supposed 256th pope, Gregory XVI, was a member of an order founded by St. Romuald at Balneo in Etruria.

The motto corresponding to John XXIII was "Pastor et Nauta" ("pastor and marine"), which is said to refer to John's previous position as patriarch of Venice. John Paul II was born during a solar eclipse, and the motto corresponding to his reign is "De labore Solis," which can be translated as "labor of the Sun" or "eclipse of the Sun." Many assumed that the next pope, corresponding to the motto "Gloria Olivae" or "glory of the olives," would have been a Benedictine monk, since the olive is a prominent symbol for the Benedictines, but Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger did choose the name "Benedict XVI" upon his election.

The prophecies end with one more pope after Benedict XVI, "Petrus Romanus," who will reign in extreme persecution.

Labels: Christian History, Ireland

Monday, September 25, 2006

Sauer & Son

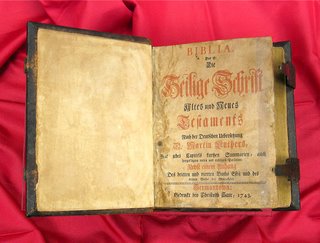

Christopher Sauer (the Elder), a great-grandfather of mine, died on this day in 1758 in Germantown, Pennsylvania.

Born in 1695 in Ladenburg, Germany, Sauer worked as a tailor and spectacle-maker there until 1724, when he brought his wife and son to America in search of religious freedom. In Pennsylvania he became associated with the German Baptist Brethren church, a non-conformist, pacifist sect. After his wife, Maria, left him to join Conrad Beissel's Ephrata Commune as sub-prioress of the convent, Sauer buried himself in his work, first as a cabinet-maker, wheelwright and clockmaker, and eventually as the first successful German-language printer in the New World. His chief rival, Benjamin Franklin, had tried to reach the German-language market in Pennsylvania with his own publications, but failed largely due to the poor literacy of his German help. Nevertheless, Franklin controlled the paper supply in Pennsylvania; and at first he refused to sell paper to Sauer for his printing press (regarding German immigrants to be poor credit risks), but later relented when a wealthy German put his credit behind Sauer's enterprise. Like Franklin, Sauer published a daily almanac (aimed at the German readership), as well as numerous religious and pacifist tracts.

In 1742, Sauer published the first European-language Bible printed in North America; up to that time, not even an English Bible had been printed in America, as that was a privilege enjoyed only by the King's printer in England. In his later years, Sauer battled against Franklin's efforts to "anglicize" the religious German immigrants and bring them under secular political influences. Sauer's wife later left the Ephrata Commune and returned to Sauer, and his son, Christopher Sower, took over the printing business and became a leader among the German Brethren.

His only child, Christopher Sower the Younger -- born on tomorrow's date in 1721 in Laasphe, Germany -- became a minister in the German Baptist Church at the age of 32, but even as his role within the church became more important, he continued to assist his father in his printing business, taking charge of the English-language publications and printing the first religious periodical in America, the Geistliche Magazien (1764).

As the American Revolution unfolded, Sower the Younger came under fire for his pacifist beliefs, which were mistaken for loyalty to England, and in 1778 Sower was arrested by the Continental Army as a spy. His print shop and all of his worldly possessions were impounded, and to add insult to injury, the Army forcibly shaved Sower's beard, which had been one of the hallmarks of his religious practice. As church historian/one-time Pennsylvania governor Martin Brumbaugh observed, "Men in public life had cleanly shaven faces. It is interesting to note that every signer of the Declaration of Independence was smooth-shaven. The indignity heaped upon Sower was two-fold. When his beard was removed his religion was ridiculed and his face was made to appear like that of his oppressors."

Sower was eventually released, but his property was never returned, and Sower lived out the rest of his years with friends and relatives. In 1792, recognizing the mistake that the Continental Army had made in its treatment of the late Father Sower, the Pennsylvania legislature passed a law giving Sower's heirs whatever remained of his confiscated property -- by that time, a regrettably empty gesture.

Labels: Christian History, Colonial History, Family History

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Berlanga

Tomas de Berlanga, a Dominican friar and bishop of Panama, died on this day in 1551 in Berlanga, Spain.

Berlanga made a career out of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. As bishop of Panama, he was directed by Charles V to go to Peru to intercede in the conflict between the joint captains of the newly established Spanish colony in Peru, Francisco Pizzaro and Diego de Amalgro. On his way from Panama to Peru, however, his ship went off course and drifted out into the Pacific Ocean, where he accidentally discovered the Galapagos Islands -- a collection of desolate lava piles which would become important 300 years later in the works of Charles Darwin, whose writings would shake the foundations of the Church which sponsored Berlanga's mission. By the time Berlanga reached Peru, Pizzaro had already sent Amalgro to Chile, rendering fruitless any attempt by Berlanga to arbitrate their dispute. Pizzaro later had Amalgro put to death.

Speaking of fruit, a persistent legend holds that Berlanga is responsible for the cultivation of bananas in the New World, having picked them up in an unscheduled stop in the Canary Islands on his way from Spain to Santa Domingo.

Labels: Christian History, Cuisine, Evolution, Exploration

Thursday, June 29, 2006

Peter and Paul

The feasts of Saints Peter and Paul, whose life-legends form much of the narrative of earliest Christianity, are celebrated today by many Christians around the world.

Peter was, of course, one of the 12 disciples of Christ. Originally called Simon, he and his brother Andrew were fishermen on Lake Galilee when Jesus called them to his side. After the arrival of John and James the Greater, the four of them -- Simon, Andrew, John and James, each hardy fisherman who could stand up to sudden squalls in the Gulf of Pigeons -- became Jesus' closest disciples, and big Simon was their spokesman and leader. Jesus nicknamed him "Peter" (the "rock"), although one of the interesting literary twists of the New Testament is that Peter seems like anything but the rock that Jesus knew him to be for much of Jesus' life story.

It is at the end, however, that Peter arises from his mistakes and shortcomings to lead Jesus' disciples and to build the church. Peter was strong and loyal, but a man of appetites and impulses; he might quibble with Jesus, stumble and lose steam, but he was warm-hearted and his faith was childlike and deep. Peter's house at Capernaum was Jesus' headquarters, and his boat was always at Jesus' disposal. When Jesus asked the disciples whom they thought he was, Peter spoke for them, saying "You are the Christ, the Son of the living God." Jesus responded by telling him, "You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church, and the powers of death will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys to kingdom of heaven." However, Peter refused to believe Jesus' prediction of Jesus' own rejection and death, and Jesus rebuked him for his short-sightedness and attachments.

At the Last Supper, Jesus again predicted Peter's future leadership, while at the same time predicting that Peter would 3 times deny his involvement with Jesus, which Peter passionately contradicted. When Jesus began to wash the feet of his disciples, Peter protested and demanded that Jesus wash his entire body. After being chosen to stand guard in the garden of Gethsemane with John and James, he fell asleep, although he did stand to brandish a sword at Jesus' captors (which again brought a rebuke from Jesus). As predicted, Peter denied his connection to Jesus on 3 occasions after the arrest, but afterward, remembering Jesus' words, Peter repented of his weaknesses.

After Christ's crucifixion and burial, Peter was the first to enter Christ's empty tomb, and was the first to whom the resurrected Jesus showed himself. During a private appearance, according to the Gospel of John, the risen Christ 3 times instructed Peter to "shepherd the flock" and "feed the sheep," in effect redeeming him for his repentance. Peter took charge of the group after Christ's ascension, and according to the Book of Acts, began to perform miracle healings in Jesus' name.

At the Council of Jerusalem, he disagreed with Paul over the desirability of a liberal policy toward Gentile Christians who did not choose to follow Jewish laws, but he agreed to the negotiated solution of James the Just that Gentile Christians could remain outside the Jewish tradition. With Paul as the crusader of the church outside Jerusalem, with Peter principally preaching at Corinth and in Asia Minor, the ways of the Gentile Christians prevailed; a new church, rather than a Jewish reform movement, was at hand.

Peter spent his final years at Rome, where he allegedly provided material to Mark for his Gospel. He was executed by being hung upside down on a cross in a general persecution of Christians in 64, and was buried, according to legend, on the site where the Vatican was built; very literally, he was the rock upon which at least the Roman Catholic Church was built. In the late 2nd century, Peter began to be identified as the first bishop of Rome, and the first in the succession of Roman Catholic popes. Having received the keys to heaven from Jesus, Peter is the protagonist of a million irreverent jokes about people trying to get in.

His comrade Paul was born a Jew whose father had Roman citizenship, and therefore he had 2 names -- the Roman "Paul" and the Jewish "Saul" after the first king of the Jews. Although his trade was making mohair for tents, Paul/Saul was an educated, Torah-adhering man whose cultural identity was as a "pharisee," a Jew who as (at least) a quasi-rabbinical defender of the Jewish traditions of the Law, was unnerved by Jesus' popularity among Jews. Along with his fellow pharisees, he saw Jesus as a symbol of the decay of the Jewish world, and he did his best to belittle Jesus' teachings -- even to the point of persecuting his followers, approving (though possibly not actually participating in) the stoning of Stephen in 34 A.D. He excelled, however, at providing the intellectual underpinnings of the pharisees' attack on Jesus: a relentless partisan with a sharp, incisive mind and quick tongue, he was not the sort of person one wanted as one's enemy.

Then, suddenly and alarmingly for one who seemed so sure of himself, Paul/Saul's world flipped upside down. According to Acts and his own testimony, shortly after Stephen's death, Paul/Saul was riding to Damascus in search of more followers of Jesus to taunt when he was knocked off of his donkey by a shaft of light much brighter than the desert daylight. Scrambling to his feet, he found that he was blind; and then, an unknown voice asked him, "Saul, why do you persecute me?" When Paul/Saul asked the identity of the voice, the voice replied, "I am Jesus of Nazareth." Paul/Saul was led to Damascus by his companions, where he rested, unable to eat or drink for several days, until one of Jesus' followers, Ananias, came to him and restored his eyesight by laying his hands on Saul.

Later, the converted Paul would say that the curious incident on the road to Damascus was the moment when the resurrected Jesus had personally visited him, just as he had visited his disciples in Jerusalem shortly after the crucifixion. Most strikingly, though, it was the moment when Paul suddenly felt empathy for the objects of his persecution, when he was able to divest himself of the comforts of his own dogma and in his blindness begin to view the world through the hopeful and compassionate eyes of Jesus' followers.

Following his conversion, Paul was as relentless in his advocacy of Jesus' message as he previously was in its opposition, focusing on the most powerful rhetorical elements of what Jesus said and did and what had happened to his followers to articulate a coherent intellectual formulation of the beliefs of the "Christians," Jesus' followers. Paul left Damascus for Arabia, where he tried out his new message: that Jesus the Messiah's baptism, death and resurrection represented for the disharmonious sons of Adam a new covenant with God in which they (we) have been entrusted with new tools to replace the Law: reconciliation, gentleness, forgiveness, compassion, love.

Paul returned again to Damascus, where his new missionary intensity was met with threats of violence, causing him to have to sneak out of town under cover of night. He continued to travel and preach, wandering into commercial centers as an itinerant tentmaker, making commercial connections with his targets, who would have the benefit of experiencing Paul as an ethical businessman before hearing his quirky message (a technique less calculatingly illustrated by Muhammad much later).

He visited Jerusalem 3 years after his conversion, arriving on Peter's doorstep like an excited fan club president coming to interview the rhythm guitarist who always stood just a few steps outside the spotlight of the rock star, talking a mile a minute. At first somewhat suspicious of this pharisee-by-reputation, the big-hearted Peter slowly realized that Paul was giving structure to his good intentions and embraced him.

With Paul's zeal came the community's first crisis: Paul had traveled to a number of places outside the Jewish world, where preaching about the Torah would have been a non sequitir; whereas in Peter's world, and that of Jesus' half-brother James, adherence to dietary laws and circumcision were part and parcel of Jesus' message. Paul the Jew struggled with this aspect of his mission, but was convinced that the central truths of Jesus' vision could be imparted to the Gentiles without requiring basic training in the Jewish tradition, and James would ultimately settle the quarrel by permitting Paul to continue his work with the Gentiles.

Paul spent the rest of his life touring and preaching, suffering persecution and hardship ("5 times have I had 39 lashes from Jews, 3 times been beaten by rods, once stoned, 3 times shipwrecked, adrift on the open sea for a night and a day . . ." and in Ephesus he was even forced to fight wild animals); but most importantly, he became the first Christian theologian, sending letters to the communities which he had seeded to provide instruction, correction and encouragement. In his Epistles to the Corinthians, the Ephesians, the Galatians, the Philippians and others, he is sometimes an impatient father who feels it is his duty to deflate self-satisfaction among the children. While readers have debated the minutiae of his advice for 2 millennia, Paul wasn't ultimately interested in clothing or hairstyles (he was, however, self-conscious about the novelty of the Christian message and therefore wanted to make sure Christians didn't go around looking too wacky), but rather the egalitarian respect and compassion with which people treated each other -- without division between rich and poor, slave and freeperson, or even man and woman.

(The most oppressive words ascribed to Paul, the misogynist statements contained in First Timothy about keeping women silent, were probably not even written by Paul, and would in any event have been inconsistent with the behavior of the early church and Paul's overarching theological concerns.)

In 58, Paul was placed in protective custody by the Romans in Jerusalem after he was beaten by a crowd of Jews at the Temple who recognized him as the Jew who taught others to forsake the Law; he was later transferred to Caesarea to stand trial for disturbing the peace and profaning the Temple, where he was held for 2 years. At the trial, he asserted his Roman citizenship and expressed his desire to be judged by the emperor. After a long and hazardous journey to Rome, Paul waited another 2 years in prison before being released in 64, but was arrested again in 67 and beheaded during the persecutions by Emperor Nero. Tradition holds that he was buried at the later site of the Basilica of St. Paul Outside-the-Walls, on the Ostia Way, outside Rome.

"If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away all my possessions, and if I hand over my body so that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing." -- St. Paul, I Corinthians 13.

Labels: Christian History

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Reinhold Niebuhr

Reinhold Niebuhr, theologian and co-founder of both the United Church of Christ (created from mergers of the Evangelical Synod, the Reformed Church and the Congregational Church in 1934) and of the Americans for Democratic Action (1947), was born on this day in 1892 in Wright City, Missouri.

Niebuhr spent his career drawing the Bible together with Western political philosophy, and his writings took aim not only at the complacency of orthodox Christianity, but also at the self-righteous secular relativity of liberal Christianity, as well as the deification of the "proletariat" by the Marxists. Recognizing the inability of human beings to transcend ego and selfishness -- admitting, unlike liberal Christians, that man is basically flawed, though capable of responding to divine grace -- Niebuhr asserts that therefore it is heresy for any church is to identify itself completely with God and to declare that opposition to its way is opposition to God's way. While Christians should never sit quietly by while evil becomes manifest, according to Niebuhr, realistically Christians are limited to trying to mitigate the influence of selfishness through contrition and the spirit of love, while recognizing that the ultimate cure for what is evil in our world can be none other than genuine, voluntary conversion and placing one's trust in God.

During the course of his career -- first as a pastor at the Bethel Evangelical Church in Detroit (1915-28), as a Socialist candidate for office (he was a supporter of the Socialist campaigns of Norman Thomas until World War II), and as a professor of theology at the Union Theological Seminary (1928-60), he turned his observations upon such social problems as racial conflict, economic injustice, industrial exploitation (becoming a harsh critic of Ford Motors' labor policies, for example) and the morality of nuclear warfare. He died on June 1, 1971 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Labels: American Socialists, Christian History, Marxism

Thursday, May 18, 2006

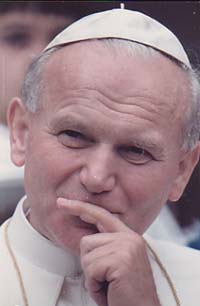

John Paul II

Born on this day in Wadowice in 1920, barely a year after Poland achieved its independence, Karol Wojtyla was the son of an intensely religious retired officer of the Polish Army. Karol's mother died when he was 10, but his native self-confidence propelled him as he became an outstanding student and athlete (a soccer goalie and an outdoorsman) with an interest in drama (both writing and acting). He entered Jagiellonian University in 1938, but after the Nazis invaded Poland in 1939, he worked as a stonecutter and a chemical plant worker during the day while by night writing for and acting in underground theater groups such as the Rhapsodic Theater of Mieczyslaw Kotlarczyk.

The Rhapsodic Theater was wholly unlike Ernst Lubitsch's comic conception of a Polish underground theater group led by Jack Benny in To Be or Not to Be (1942); its defiance was not about spy-capers and fake beards, but about propping up the beleaguered patriotic spirit of the Poles through the clandestine performance of Polish-language works in violation of Nazi prohibitions. For Wojtyla, the defiance of the Rhapsodic Theater was inextricably linked with the hope provided by the teachings of the Roman Catholic church, a point of view he inherited from his father, who hoped he would study for the priesthood.

Following his father's death in 1941, it was with a measure of both patriotism and piety that Wojtyla eluded the Nazi standing order for the arrest of all young Polish men in Krakow and resumed his religious instruction in the underground seminary of Cardinal Adam Sapieha, the archbishop of Krakow.

After the end of World War II he resumed his studies openly, earning his degree in theology from Jagiellonian in 1946 while continuing to pursue his literary activities. In March 1946 he published his first collection of poems, Song of the Hidden God; and 8 months later he was ordained as a Roman Catholic priest. Sapieha sent Wojtyla to Rome to earn his doctorate, which he did in 1948 with a dissertation on faith according to St. John of the Cross. After serving as a parish priest in Krakow, he returned to Jagiellonian to study philosophy (particularly the ethical writings of Max Scheler), and he accepted an appointment as a professor of ethics at Lublin, where he gained a reputation as one of Poland's chief ethicists.

In 1958, Pius XII named Wojtyla bishop of Ombi. Shortly thereafter, he published his first major ethics work, a treatise on sexuality called Love and Responsibility (1960), which Paul VI would later rely upon heavily in writing his encyclical Humanae vitae (1968); in it, Wojtyla portrays sex as a mystery encompassing both body and soul, which is why he believes it is wrong to separate the bonding that comes through healthy sex from the act of procreation; artificial contraception, in Wojtyla's view, limits one's ability to give fully of one's self and creates distance between a husband and wife by denying part of the mystery. (As pope, he would reaffirm his support for Paul's Humanae vitae in Chicago in 1980, a source of concern particularly for progressive American and Western European Catholics who believed that the Church was out of touch with modern issues of sexuality such as abortion, homosexuality and birth control).

Wojtyla participated in Vatican Council II (1962-5, called by John XXIII), not only having a major influence on the Church's statements on its role in the Modern World and the doctrine of religious freedom, but showing himself to be a consummate networker, gaining world renown within the Church. In 1963, Paul VI named him archbishop of Krakow, and created him a cardinal in 1967.

During the 1970s, Wojtyla became a major voice in Poland against the Communist regime, working to secure greater tolerance for the activities of the Church. After the deaths of Paul VI and his successor, John Paul I, within scarcely a few months, the widely admired Wojtyla, at the relatively young age of 58, was elected pope on October 16, 1978 -- the first non-Italian pope to be elected since Adrian VI (Dutch, elected 1522). He took the names of his three predecessors, evidencing his will to carry out the aims of Vatican II.

The following year, he exhibited both his personal charisma and the influence of his pulpit by visiting his Polish homeland and meeting with the leader of the Solidarity anti-Communist movement, Lech Walesa; it is said that by his visit, John Paul II gave the Polish people the confidence to fight for freedom, and was the catalyst at the beginning of the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe and in Russia during the 1990s. It was an impressive debut performance in this service of John Paul II's ideas about the role the Church should play in a world increasingly violent world: the pope would make almost 200 official visits throughout the world, more than all his predecessors combined, in an effort to leave behind his personal imprint of love and peace.

His trips were all exceptionally well-staged and media-savvy, beginning with his ritual of kissing the ground of the foreign land he was visiting, followed by open-air masses attracting hundreds of thousands of listeners, and the delivery of homilies which gently drew upon local topical concerns. His instincts as an old actor were sharp; during a gathering in New York's Central Park in 1995, the aging pope paused during the delivery of a homily to sing a few bars from one of his favorite Polish Christmas carols, to the roaring approval of the crowd. "And to think," the Pope quipped, with comic timing worthy of the aforementioned Jack Benny himself as observed by one commentator, "you don't even know Polish."

Although he was seriously wounded in an assassination attempt in 1981 and some time later began to show the effects of Parkinson's Disease, John Paul II refused to simply take it easy, and in addition to his travels found new ways of reaching the public, publishing a bestselling book, Crossing the Threshold of Hope (1994) and releasing a hit CD of spoken words and chanted prayers accompanied by classical and contemporary music, Abba Pater (1999).

After his death on April 2, 2005, 4 million people from around the world converged upon Rome for his funeral, chanting "Santo subito!" ("Saint soon!"), as commentators observed that he was the one human being who had been seen in person by the largest number of other humans in the entire history of the planet.

Labels: Christian History

Tuesday, May 09, 2006

The Catholic Worker

"The trouble with the world is that the man of action does not think and the man of thought does not act." -- Peter Maurin.

Short, stocky, unkempt and possessed of a strong French accent, Peter Maurin pushed his way into the cloistered consciousness of Catholic America, posing as the belching tramp at the country club picnic to call attention to the religious component of political issues such as economic inequality, workers' rights, anti-Semitism and the U.S. war machine.

Born on this day in 1877 in Oultet, Languedoc, France, the son of a landowning farmer, Maurin became a novice in the Christian Brothers order at age 16, and during his early adulthood (after his vows expired in 1903) he worked with Le Sillon, a pro-democratic, anti-capitalist Catholic youth movement. He soon left the movement, impatient with its being long on parades and short on substance. Influenced by the writings of Peter Kropotkin and Leon Bloy, Maurin cultivated the impoverished lifestyle of the wandering manual laborer, arriving in the U.S. in 1911 to work in the Pennsylvania coalfields and in other physically demanding jobs. He also dressed the part, wearing rags and bathing rarely.

While acting as a caretaker at a Catholic day camp, he gave free French lessons at an artist's colony in Woodstock, New York, traveling to New York City on the weekends to read in the public library and talk to the radicals in Union Square. Informed by his reading and experience among the social outcasts, Maurin began to aggressively advocate "Utopian Christian Communism," which featured voluntary poverty (so as to decrease dependence on government), Christian communal housing and a return to agriculture and manual craftsmanship, with worker ownership of the means of production.

Through his radical connections he met Dorothy Day, a Catholic journalist who eventually masterminded the development of a movement based on Maurin's philosophy, named after the newspaper the two founded in 1933, the Catholic Worker. Maurin contributed regularly to the newspaper, writing "easy essays," short expositions of social observation sharpened with expressions of Catholic faith.

Although Maurin was perhaps more radical than some of his colleagues (he sometimes gave frigid support to unions and Roosevelt's New Deal on the grounds that they perpetuated capitalism), the Catholic Worker movement attracted young Catholic intellectuals and inspired the establishment of several Catholic communal farms. From his position of influence, he spoke out against Catholic support of Franco in Spain, the bigotry of Father Coughlin, and U.S. involvement in World War II -- all the while continuing to work at manual jobs. He retired due to ill health in 1944, and when he died on May 15, 1949 in Newburgh, New York, he was buried in a donated burial plot wearing a donated suit.

Labels: Christian History

Monday, May 01, 2006

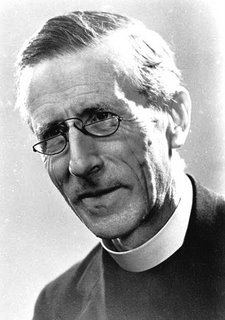

Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born on this day in 1881 in Sarcenat, France.

The son of a farmer and amateur naturalist, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin entered the Jesuit College at Mongré at the age of 10, and joined the Jesuit novitiate when he was 18. After the Waldeck-Rousseau laws forced the Jesuits to flee France, Teilhard began a period of exile on the Isle of Jersey (going on geologic field trips), in Cairo and elsewhere in Egypt (teaching physics and chemistry at the Jesuit College and continuing to study geology), and finally in Hastings, Sussex, where he was ordained as a priest in 1911 at the age of 30.

Rather than pursuing a career in the Church, however, Teilhard went to work in the paleontology laboratory at the Museum of Natural History in Paris until the beginning of World War I, when he joined the French 8th Regiment of Moroccan rifleman (later the 4th Regiment of Zouaves and Light Infantry) as a stretcher-bearer. By the War's end, he had completed his novitiate during a leave (taking his solemn vow to enter the Jesuit brotherhood) and received the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille Militaire for his heroism. Teilhard later wrote that the "war was a meeting . . . with the Absolute," inspiring him to write an essay, "The Cosmic Life" -- a first, furtive explication of his developing ideas of science, philosophy and mysticism -- although, during his lifetime, most of his published works concerned mammalian paleontology and Asian geology.

As early as 1924, Teilhard's earnest attempts at drawing modern science together with Roman Catholic dogma (specifically, an attempt to reconcile the concept of "original sin" with evolution) were greeted coldly by ecclesiastical authorities, and he was basically forbidden to publish his spiritual writings. Teilhard, though patient and respectful, lived a double life -- outwardly devoting himself to geological expeditions throughout Asia and gaining worldwide renown for his scientific contributions, but privately continuing to write down his meditations.

Beginning in the mid-1920s, Teilhard went to China, where he worked on the Chinese national geological survey and assisted archaeologist Pei Wenzhong at the unearthing of the first discovered skull of the hominid "Peking Man" (1929). During 1930-1, he explored the Gobi with Roy Chapman Andrews' American Center-Asia Expedition and participated in Georges-Marie Haardt's "Yellow Cruise" along the old Silk Road in a fleet of Citroën P2s, joining the group in Beijing and traveling to Urumqi, the capital of Sinkiang.

In 1937, he wrote The Divine Milieu while sailing on the Empress of Japan to the U.S., where he was given the Mendel Medal at Villanova. On that occasion, he gave a speech about evolution, prompting the New York Times to portray him as the Jesuit who claimed that man was a mere instrument of evolution; Catholic University of Boston, which had been scheduled to bestow an honorary doctorate upon him, quickly called him to cancel the honor. Adding insult to injury, as it were, in 1950 Pius XII issued the encyclical Humani generis, which came to be seen as a harsh retort to Teilhard's requests for permission to publish his theory of evolution.

Just what was the substance of Teilhard's questionable writings, which eventually came to be published after his death and were influential enough to merit an advisory by the Church against uncritical acceptance of his ideas? In The Divine Milieu and The Human Phenomenon, Teilhard advances the notion that evolution is a divine process resembling "a way of the Cross" for all life on Earth. Classical theology, in Teilhard's view, can be harmonized with modern scientific thought, particularly about evolution, if one accepts the idea that basic material processes such as gravity, inertia and electromagnetism have contributed toward the creation of increasingly complex entities, from atoms to molecules to cells, and ultimately to the aggregation of biological systems we know as human beings -- entities that are possessed of self-awareness and that are capable of moral responsibility. At the same time that evolutionary processes have contributed to the diversity of species that currently exist on Earth, Teilhard's fundamental starting point is that "each one of us is perforce linked by all the material organic and psychic strands of his being to all that surrounds him."

For Teilhard, evolution is the process of the physical and moral convergence of these strands (affecting both the biosphere and the "noosphere," the sum total of the cultural achievements of humanity) which is aimed at a complete and final unity with God called the "Omega point" -- a kind of superconsciousness of all life on Earth, similar in some ways to Bruno's "world-soul" or Lovelock's concept of Gaia. In his belief in evolution as a process of transcendence, Teilhard provides his readers with a glimpse of a kind of cosmic redemption, ultimately summarizing his equation of science and theology with the optimistic assertion that "Christ is realized in evolution."

He died on April 10, 1955 in New York City.

Labels: Christian History, Evolution, Geology

Friday, April 21, 2006

Heloise and Abelard

The forbidden love affair of Heloise and famed theologian Peter Abelard has inspired writers for centuries: Jean de Meun, Francois Villon and Alexander Pope, among others, kept the legend alive for future generations, as did the novelist George Moore with his popular novel Heloise and Abelard (1921); and meanwhile, the jilted, the lovesick and the romantic at heart have been making pilgrimage to the tomb of Heloise and Abelard at Pere Lachaise in Paris for years. As Mark Twain cynically observed, "Go when you will, you will find someone snuffling over that tomb."

Born to noble parents in Brittany in 1079, the handsome, proud young Peter Abelard steadily won fame as a teacher throughout France as he roamed in academic circles like some kind of a scholastic gunslinger, knocking off the local champion with his superior logical and rhetorical skills. Stimulated by controversy and bored by lectures, Abelard helped to foster the rebirth of the Socratic dialogue as a teaching method in medieval France, shedding light on complex issues by assaulting his students with probing questions.

He was at the top of his game as head of the Cloister School in Paris when, in his 40s, he met the 18-year old Heloise, a niece of one of the local canons, and herself a renowned scholar -- not leastly for the fact that a woman who could read and write was a complete anomaly at the time. He consented to become her teacher, but soon found himself seducing her. She fell in love with him completely, and soon the two scholars were living recklessly and making love without inhibitions. Abelard abandoned his other pupils and allowed his love songs to Heloise to be sung in public. Angered by the gossip, Heloise's uncle Fulbert tried to separate them, but they took even greater chances to be together, and soon Heloise found she was pregnant with Abelard's child. Abelard whisked her off to Brittany to stay with his family, where she gave birth to their son, whom she named Astralabe; Abelard's sister took the child at their request and raised it as her own.

Abelard returned to Paris. With an outward veneer of invincibility, he had always aspired to the chastity of St. Jerome -- an element of character that he believed to be essential to his own fame as a scholar. Nevertheless, Abelard made an offer to Fulbert to marry Heloise to quell his anger, as long as the marriage could be kept a secret -- thus preserving at least publicly his reputation as a peer of Jerome. Fulbert accepted Abelard's offer, but Heloise protested to Abelard, realizing the futility of the gesture. Abelard prevailed: the two passed a night of secret vigil in a Paris church and at daybreak received the nuptial blessing, witnessed by Fulbert and a few friends.

If Abelard thought he could save his reputation in this way, he misjudged Fulbert, who spread the news of the marriage in order to save his own face. Abelard and Heloise denied the marriage, and as if to prove that it never happened, Abelard sent Heloise to live at Argenteuil to her old convent school, where she masked her connection with Abelard by entering religious life as a nun. Now Fulbert thought himself to be deceived by Abelard, that Abelard went through the charade of a sham marriage just to be rid of Heloise. In his anger, Fulbert and several allies crept into Abelard's Paris quarters one night and violently castrated him.

Abelard's guilt over giving in to his fleshly desires and over ruining Heloise's life, was unbearable, shattering all aspirations he had to be a great philosopher. In his shame, he became a monk at the Abbey of St. Denis near Paris in 1119, where he earned a reputation as an exacting theologian, criticizing the other monks for their disingenuous lifestyles. Making no friends at St. Denis and finding his major work of theology, Theologia, condemned and burned at the Council of Soissons in 1121, Abelard briefly and unsuccessfully served as abbot at the remote monastery of St. Gildas, and finally went off to live on some land donated to him by a sympathetic friend called the Paraclete, where he established a modest religious community. He donated to community to Heloise in 1129 for the foundation of a convent, of which she became the prioress.

While outwardly, Heloise was a model nun, widely admired for her commitment to prayer, inside she was in agony, still deeply in love with Abelard. In a series of letters to Abelard written during the 1130s, she curses God and yearns for their reunion. In one letter, Heloise writes: "I am still young and full of life; I love you more than ever and suffer bitterly from living a life for which I have no vocation . . . I who should tremble at what I have done, sigh after what I have lost." In his half of the correspondence, Abelard also shows himself to be devoted to Heloise, but does his best to seek her forgiveness and attempt to convince her to accept God as her master in place of him.

Meanwhile, in 1135, Abelard moved to Mont-Sainte-Genevieve outside Paris and again became a celebrated teacher and philosopher. During this period, he wrote furiously: he completed a second edition of his controversial Theologia; composed his Dialogue between a Philosopher, a Jew and a Christian; and in his Ethica, he espoused the revolutionary idea that human actions do not make a person better or worse in the sight of God, but rather that it is the intentions behind the actions, the consent of the mind, that makes a sin. He attracted many pupils, including John of Salisbury and future Popes Celestine II and Celestine III, but he also attracted the hostility of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, who criticized Abelard's exercises in logic as revisions of basic Christian dogma. Leading the Council at Sens in 1140, Bernard condemned Abelard and his work, a decision upheld by Pope Innocent II.

Devastated, Abelard withdrew to Cluny, where the abbot Peter the Venerable succeeded in mediating his conflict with St. Bernard. Sick and old but finally at peace, Abelard died at Cluny(on this day in 1142) as a most modest and unassuming monk. His body was transported to the Paraclete, and when Heloise died 21 years later her last wish to be buried with him was honored, first at the Paraclete and eventually at Pere Lachaise in Paris.

It is not known whether Heloise ever found peace with the God whom she had cursed; however, she may have felt some comfort at the words of Peter the Venerable: "Venerable Sister, he to whom you were joined first in the flesh and then by the stronger and more perfect bond of divine charity, he with whom and under whom you too have served the Saviour, is now sheltered in the bosom of Christ. Christ now protects him in your place, indeed as a second you, and will restore him to you on the day when He returns from the heavens between the voice of the archangel and the sounding trumpet." Or perhaps not.

Abelard's passion for classical antiquity, and the anguished, personal analyses he revealed in his writing have led some critics to identify Abelard as an intensely bright precursor of the Renaissance -- two centuries before it came to pass. However, it has been the status of these lovers as characters in a legend of reckless and forbidden love, the kind of love that makes you want to rip your own head off -- if you will, a kind of medieval 'Sid-and-Nancy' tale, inside-outsky, where instead of heroin and the punk sub-culture, the drug of choice was pride and their milieu the impossible purity of the Academy -- that keeps Abelard and Heloise alive for us today.

Labels: Christian History, Literature

Wednesday, March 22, 2006

Armageddon

THE PRESIDENT: The answer is -- I haven't really thought of it that way. (Laughter.)

-- from a transcript of President Bush's visit to the City Club of Cleveland, March 20, 2006.

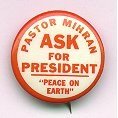

Doomsday prophet Mihran Ask was born on this day in 1886 in Shabin Karahisar, Sivar Province, Western Armenia, Ottoman Empire.

Doomsday prophet Mihran Ask was born on this day in 1886 in Shabin Karahisar, Sivar Province, Western Armenia, Ottoman Empire.A pastor of the Remnant Church in Gilroy, California, Ask declared in January 1957: "Sometime between April 16 and 23, 1957, Armageddon will sweep the world! Millions of persons will perish in its flames and the land will be scorched!"

In case you missed it, he was wrong. The only item of note during that period appears to have been President Eisenhower's appropriation of $41 million for the U.S. Postal Service. Ask's prediction was even embarrassing to the perennial heralds of doom, the Jehovah's Witnesses, who wrote that "(s)uch false prophets tend

to put the subject of Armageddon in disrepute."

to put the subject of Armageddon in disrepute."Ask went on to run for U.S. president in 1964 (perhaps he was upset with Eisenhower over that postal appropriation) as the self-proclaimed candidate of the Peace Party. He is said to have received a grand total of 10 votes in all.

He died February 6, 1979 in Morgan Hill, California.

Labels: Christian History, Presidential Campaigns

Friday, March 17, 2006

St. Patrick

Don't say it too loudly -- especially not around my red-headed wife's family, all those Rays and Murphys and O'Connells and McFaddens and Donahues.

Shhh. The patron saint, nay, the symbol of Ireland . . . was a Romanized Brit.

This hardly matters to the revelers who consume thousands of gallons of beer (green-dyed and otherwise) in St. Patrick's Day celebrations -- any more than the fact that George Washington was a Brit has ever bothered any of the people who celebrate the 4th of July, or the fact that Cleopatra was a Greek has ever bothered a Hollywood casting director. Still, in the politically-charged days since the Elizabethan colonization of Ireland in 1556, it's better to whisper Patrick's ethnic origins if one is to mention them at all.

Patrick's father was a middle-class deacon and bureaucrat, which meant that Patrick could have expected to enjoy a decent education and livelihood; but at 16, Patrick was kidnapped by Irish pirates who attacked his father's farm in England, and he became enslaved for 6 years. During the near-starvation and other privations of his captivity, Patrick sustained himself with his faith in God, away from clerics or formal instruction.

At the end of 6 years, a mysterious voice told him that he was going home, whereupon he was either freed or he escaped from his captivity, walked 200 miles to the Irish coast, and hitched a boat back to England. There, after reuniting with his family, Patrick was visited by another divine messenger who revealed what was to become Patrick's calling: to bring Christianity back to the land of his captors, to become a civilizing voice among the Irish or vox hiberionacum.

He received rudimentary training for the priesthood (lacking a complete classical education, something which he would always regret) and returned to Ireland around 435, working principally from Armagh in the North. Although legends credit him with single-handedly converting the whole of Ireland (using the three leaves of the shamrock to explain the Trinity), in actuality his mission concerned itself with organizing his small flock into a church administration, and turning them upon the rural Irish to stamp out idolatry and sun-worship.

His two rough Latin works (a Confession, and an Epistle, in which he denounced the treatment of Irish captives by a Briton chieftain) are the earliest surviving Irish texts, revealing a humble man who was conscious of his status as an intellectual exile as well as a physical one. By a few hundred years after his death, he was credited with a number of tall miracles, including driving all of the snakes off of the island, and certainly the metaphoric significance of that tale has fueled much of the Irish nationalistic spirit with which he later became identified.

It doesn't explain the green beer, however.

Categories: Christian-History, Ireland

Labels: Christian History, Ireland

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

Aquinas

St. Thomas Aquinas died on this date in 1274 at Fossanova around the age of 50.

The youngest son of an Italian count, Tomasso d'Aquino was sent to the Benedictine monastery at Monte Cassino at the age of 5, but when Emperor Frederick II was excommunicated, the monks went into hiding, and Thomas resumed his education in Naples. There Thomas encountered not only the works of the Christian fathers, but in the shadow of Frederick's intellectual tolerance, new exposure to Islamic and Greek writers such as Ibn Rushd and Aristotle. Excited by this intellectual climate, Aquinas decided on a life of study, preaching, teaching (and poverty), and attempted to join the Dominican brotherhood in 1244.

His family was apparently against the idea, imprisoning him in their castle for a time. His older brothers tried to break his resolve by sending a prostitute into his room; according to legend, Aquinas drove her away with a burning stick from his fireplace. After they relented, Aquinas studied under Albertus Magnus in Cologne, where he acquired the nickname "Dumb Ox" -- not so much for his intellect, but for his massive, slow physique. Albertus would say: "We call him the dumb ox, but the bellowing of that ox will resound throughout the whole world."

In 1251, he was ordained a priest and went to Paris where he received his masters in theology in 1256. Although he was modest and unassuming, Aquinas quickly became a master of the scholastic method of teaching, which entailed reading to a small group of students from a theological text (Peter Lombard's Sentences, 1148-51, a collection of opinions from church fathers, was the basic one), briefly explaining the point being made, and then analyzing the questions presented by it.

Within the swirling currents of the "new" Islamic and Greek philosophers posing questions about the existence of the world which did not seem to be adequately answered by the early church fathers, Aquinas increasingly found his scholastic analysis feeding on and reacting to Greek and Islamic sources, employing Ibn Rushd and Aristotle as counterpoints and methodological guides. He masterfully synthesized the disparate perspectives of the church fathers, and harmonized the "natural reason" expounded by the "new" philosophers with reasonable and rationally defensible Christian faith.

Where St. Augustine and his followers had proposed an unadorned faith through the notion that human reason had been hopelessly tarnished after the Fall of Adam and Eve, Aquinas, in his master work, Summa Theologica (c.1265-73), preferred to maintain that natural reason could be used to discover some extent of truth through the study of the evident effects of God's work in the world, and that grace completes the picture by filling in what cannot be learned from reason alone.

From this foundation, he created his "5 proofs" of the existence of God: (1) everything that is moved must be moved by something else, and since there is motion there must be a first mover; (2) from the sequence of efficient causes in sensible things, we can deduce a first efficient cause at the beginning of the sequence, which is God; (3) something in existence is necessary, and we may suppose that God is that which does not owe its existence to anything else, but is the cause of all necessity; (4) "more" and "less" are aspects of "greatness," which must be a reflection of some perfect "greatness" we call God; and (5) from the existence of "governance" and "guidance" as structures within the world, "there is therefore an intelligent being by whom all natural things are directed to their end. This we call God."

Writing Summa Theologica was an obsession for Aquinas: he ate and slept little during the years of its composition, and employed up to 4 secretaries at a time to take dictation on up to 4 topics at once; some even said he dictated in his sleep. Then, on December 6, 1273, he suddenly stopped dictating, apparently suffering a stroke during the Wednesday morning mass. With impaired speech, he answered a follower who asked why he had stopped working on the Summa Theologica, "I cannot [continue] because all that I have written seems like straw to me." Asked by Pope Gregory X to attend a council at Lyons, he died during the journey.

He is depicted in Dante's Divine Comedy as the vehicle by which the pilgrim may obtain knowledge as he yet climbs to heaven -- which is perhaps a fair distillation of what Aquinas was all about. He was canonized in 1323 and declared a "doctor of the church" in 1567 -- no mean feat for a man who, by nuance and rigorous logical discipline, managed to use the words of heathens to infuse the chaos of early Roman Catholic theology with a structure which would endure for centuries.

Labels: Christian History, Italy, Philosophy

Friday, February 10, 2006

'Against Such Things There is No Law'

Marxist legal theorist Evgeny Pashukanis was born on this date in 1891.

A Russian of Lithuanian parentage, Pashukanis joined the Bolsheviks in 1912, and following the Russian Revolution in 1917 became a leading writer in Soviet jurisprudence. Unlike other Soviet legal writers, however, who thought that pre-Revolutionary forms (i.e. laws and courts) could be adapted to serve the cause of the Revolution by changing the content of the laws and putting revolutionaries in positions of authority on the courts, Pashukanis' critique began with the radical view that the concept of "law" itself was an outgrowth of capitalist society -- a product of the capitalist's desire to protect property and dominate the proletariat -- and that in its highest evolution a post-capitalist society would see a "withering away" of the law in favor of new forms of social behavior and organization based on the absence of commodity fetishism, much like the "withering away of the state" proposed by Karl Marx himself.

Pashukanis' vision of a disappearance of laws echoes the brash optimism of a revolutionary from another period -- the Apostle Paul in his Epistle to the Galatians, in which he writes: "Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law, having become a curse for us . . . Stand firm therefore in the liberty by which Christ has made us free, and don’t be entangled again with a yoke of bondage . . . the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faith, gentleness, and self-control. Against such things there is no law."

There is, of course, much that separates theoretical Christianity from theoretical Marxism -- but at the core of both Paul and Marx was a fervent belief in the better part of one's nature, unlocked within a new order of social relations, as well as a hopeful expectation of ethical expression that can only come from within, and not from an old set of rules.

Pashukanis' critique of the nature of legal authority was destined to be short-lived within the atmosphere of terror imposed by Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin, who gave lip service to Marxism as Pashukanis and the theorists saw it, but ruled as a despot. At the age of 46, Pashukanis was murdered by Stalin's secret police, and his writings were burned by the Soviets, only to reappear in translation in the 1950s.

Labels: Christian History, Juris History, Legal History, Marxism, Philosophy

Friday, January 06, 2006

Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc, soldier and saint, is said to have been born on this day, c. 1412, in Domremy, France.

She grew up around soldiers armed for battle, and knew well the trappings of knighthood from an early age. Her hometown was divided by a tributary of the Meuse, and each bank was controlled by opposing factions within the conflict known as the Hundred Years' War, an atmosphere of bloody skirmishes: on the south, supporters of the Anglo-Burgundians who favored English king Henry V's claim to France held sway; on the north, vassals of the native French crown. Joan's allegiances were with the French, especially after the Burgundians rudely torched Domremy in July 1428.

Even before that cataclysmic event, however, as early as 1425, Joan later admitted to hearing voices during the ringing of the church bells (voices she later identified as coming from St. Margaret of Antioch, St. Catherine of Alexandria and the archangel Michael), but she kept them to herself until February 1429, when she approached the captain of a nearby town militia and asked him to provide her with an escort to the French royal claimant, Charles the Dauphin, who was cowering in his court at Chinon.

According to her own testimony, she entered Charles' hall wearing men's clothes, and out of the crowd of people assembled her voices led her to recognize Charles, whom she had never seen before. Addressing him, she told him that God had sent her to wage war against the English, and that God had also told her that Charles would possess all of France as its king.

Many have questioned why Charles would choose to give a second thought to a short-haired peasant girl wearing trousers and a tunic, even if she was earnest and spirited: while he did send her to be questioned by his panel of experts, the truth was that "prophets" who claimed to hear voices were not uncommon in 15th century France, and that one should approach Charles with good news was indeed good news for Charles, who at that moment had little confidence in his ability to beat the English. After all, he probably thought, what if she's right? Charles gave her armor, a standard bearing the motto "Jesus and Mary," and an armed platoon of escorts, sending her quietly and in an unofficial capacity to Orleans, which the English had kept under siege since the previous October.

She began her work not as a soldier, but as a kind of "Tokyo Rose," warning the young English king Henry VI in a letter she dictated at the end of March: " . . . I am a chieftain of war and whenever I meet your followers in France, I will drive them out; if they will not obey, I will put them all to death . . . I am sent here in God's name, the King of Heaven, to drive you body for body out of all France."

Entering Orleans on April 29, she inspired the French to action, and was at the front of the charge, the first to put a ladder to the largest English bastion, when she was wounded by an arrow to the chest. While she recovered, her example kept the French troops at their work, and on May 8, 1429, the English finally retreated and the siege was broken. The victory renewed the French spirit, and Joan suddenly found herself in a position of influence. Convincing Charles that he needed to take Rheims and stage a proper coronation, she led her troops to 4 victories in one week in June 1428 on her way there.

Joan's proudest moment came on July 17, when Charles was crowned Charles VII, king of France. Joan next set her sights on Paris, which she attacked in September; but Charles withdrew his support for the campaign while he awaited a diplomatic solution with Burgundy, and Joan was beaten back. After 6 months of cooling her heels, Joan decided to attack the Burgundians at Compeigne, which had recently been recaptured for the English, in May 1430, but in the chaos of a French retreat she was captured.

The Burgundians held her for a few months (during which she attempted to escape by leaping from a high tower), but eventually they sold her to the English, who, in an attempt to destroy her influence, handed her over to ecclesiastic court headed by Bishop Cauchon at Rouen to try her on charges of heresy.

During the 14 month trial, Joan showed fortitude and common sense, as well as flashes of mischievous wit: when asked if her voices wore clothing when they revealed themselves to her, for example, she chided her interrogators for suggesting that God was too cheap to clothe his messengers. By the end of the trial, however, Cauchon and his panel had weakened her. She was convicted on 12 counts (including faking her visions, dressing as a man, and believing that she was directly responsible to God rather than the Church); afterward she was tricked by Cauchon into signing a confession that all she had done was in the service of Satan, and compliantly changed into women's clothing.

Days later, when she discovered the effect of her confession, she boldly appeared in trousers again, leading a secular court to sentence her to be burned at the stake as a relapsed heretic. Her execution took place on May 30, 1431 in Rouen. As the flames rose up, she cried "Jesus" 6 times; and afterward, the fire was raked back, to show that she had died, and to show that she was indeed just a young girl. Charles VII, it is often observed, did nothing to rescue her, but in 1456 after he had finally taken Rouen, he conducted a posthumous trial and annulled her verdict of guilt.

Her life became rich material for writers, although in the first years after her death she was often seen as a sorceress in league with hell, or worse yet, as Shakespeare depicted her in Henry VI, Part I, as an oversexed collector of men's souls. By the 19th century, however, her unwavering principles and devotion to God led even the British (such as Carlyle, Southey and DeQuincey, among others) to admire her. By the time she was canonized by Benedict XV in 1920 (almost 500 years after her death), she became a much more pliable symbol of feminine heroism, embraced by French patriots and by soldiers (during World War II, by both the Vichy government and the French resistance movement); by lesbians and by feminists; by Protestants who saw in her the prototype for intimacy with God, and by Catholics as a virgin mystic who faced what she believed to be the will of God with complete integrity.

Labels: Christian History, Trailblazing Women