Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (whose full name was translated by G.V. Desani as "Action-Slave Fascination-Moon Grocer") is often credited with securing independence for India from the British. While it is true that no other individual could claim more credit for turning the infant crusade for Indian independence into a national movement, representing all classes of Indian society, critics have since pointed out that Gandhi achieved neither a unified independent India nor peace. Nevertheless, revolutionaries around the world have galvanized around the memory of the Mahatma, seeing him almost as a miraculous living confluence of human kindness and political change, of faith-based theory and effective practice.

Born on this day in 1869 in Probandar, India, the son of a prime minister of the tiny principality of Porbandar, Gandhi was married at 13. Three years later he suffered self-loathing disgrace which would never leave him and which would predispose his philosophy and public persona: he was making love to his wife when a servant brought him the news that his father had died. "The shame to which I have referred . . . was this shame of my carnal desire even at the critical hour of my father's death, which demanded wakeful service." This incident, along with his mother's teaching of devotion to rituals of self-suffering, led him inch-by-inch to live as an ascetic, forsaking sexual relations (after fathering 4 children) and scaling down to a simple agrarian life.

When he was 19, however, his family expected him to be a professional, and he was sent to England to qualify as a barrister, where in addition he studied the New Testament, Buddha's sutras and the Bhagavad Gita while avoiding Western temptations. When he returned to India in 1891, he was not considered to be the brightest of lights, seeming too shy for litigation, and after 2 years he moved to South Africa, then also a possession of the British Empire. To his surprise, he discovered that as an Indian he had no rights in South Africa, and soon he found his voice and vocation as an activist.

Drawing from his religious studies and from works by Tolstoy and Ruskin, among others, Gandhi developed the three principles by which he would conduct his life and causes: satyagraha ("truth-force," denoting "the method of securing rights by personal suffering; it is the reverse of resistance by arms," bringing injustice to an end by changing the hearts of the oppressors though love and self-suffering), ahimsa (non-violence) and brachmacharya (sexual abstinence).

He put satyagraha to the test in civil protests over racial discrimination in South Africa, leading thousands of ethnic Indians in publicly refusing to submit to the ignominy of registration and fingerprinting in 1907, resulting in Gandhi's arrest and conviction the following year; and leading a massive general strike to oppose a court ruling that non-Christian marriages were not considered legal in South Africa. He was again arrested, along with thousands of others, and released after reaching a watered-down compromise with South African general Jan Christian Smuts over the future treatment of ethnic Indians. During this period, he also experimented with communal living, setting up the Phoenix Community near Durban and the Tolstoy Farm near Johannesburg; but after the compromise with Smuts, he returned to India in 1915.

Within 5 years, he became the leader of the Indian nationalist movement, spearheading nonviolent protests in Champara to improve the conditions of indigo farmers (1917) and in Ahmedabad on behalf of textile workers (1918), building support for his views among the working class; and, as leader of a reformed Indian National Congress, a noncooperation movement against British rule in response to the slaughter of hundreds of Indians demonstrating for independence at Amritsar (1919-22) which attracted the support of the Muslim community. Gandhi suspended the latter program, however, when a violent protest broke out in Chauri Chauri, resulting in the death of 22 policemen inside a building burned down by independence protesters.

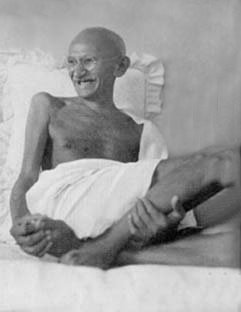

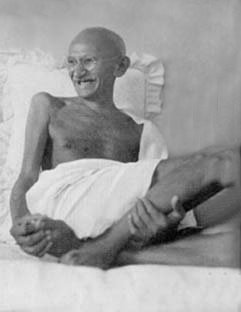

Suspending the movement did not endear him to militants who sought independence at any cost, and there was no outpouring of rage when Gandhi was sentenced to 6 years in prison for inciting the movement. Gandhi was freed after serving only 2 years, and emerged to find Hindu and Muslim factions of the Indian National Congress arguing over methods and strategies. His reaction was to undertake a much-publicized fast in protest of the in-fighting, a satyagraha technique which became his hallmark in the years which followed. By this time, Gandhi had shed the Western suit and tie he wore as a barrister in favor of dhotis (white traditionally-Indian wrap-around garments), shaved his head and immersed himself in collective farming -- consciously adopting a luddite persona and luddite practices as a way of separating himself (and ultimately his followers) from England, its European fashions, and what he viewed as its soul-killing and politically oppressive industry and technology.

In 1930, when he reemerged as the architect of Indian protests against the Salt Act (which required Indians to buy salt from the British government) by leading thousands of Indians in a 200-mile nonviolent march to the sea to make salt by hand from ocean water, Gandhi was internationally recognized as the personification of colonial peoples desiring self-determination. The march sparked another round of mass noncooperation, and fostered international sympathy for the Indian cause for which the British government was entirely unprepared. (Evidence of his impact can be seen in his being named

Time's "Man of the Year" in 1930).

Both sides called a truce as Gandhi was invited to England to negotiate a compromise. Reveling in the consciousness-raising publicity, he took tea with George V wearing nothing but a "loincloth" ("the King was wearing enough for both of us"); and while the talks resulted in no great progress, British rule was becoming less tenable as Gandhi renewed the civil disobedience movement upon his return to India. He was arrested again, but his presence was felt nonetheless when he undertook 2 lengthy fasts in response to proposed constitutional provisions for a separate, marginalizing electorate for the harijans (the "untouchables," the lowest caste of Hindus), exerting moral pressure on the British to propose an alternative structure.

In 1934, Gandhi resigned from the Indian National Congress, by this time headed by his friend Jawaharlal Nehru, but continued to be a mentor to Nehru. As World War II began in Europe in 1939, the Indian National Congress proposed to press the cause for independence in exchange for India's support of the British war effort, while Gandhi was concerned about England's ability to use the independence issue to issue to drive a wedge between Hindus and Muslims to delay the inevitable.

While the Muslim League, led by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, curried favor with the British by pledging support for the war, Gandhi went public with a more radical stance, calling for the immediate withdrawal of the British from India during a crucial moment in the war during the summer of 1942 (the "Quit India" declaration) and declaring that all Indians should engage in one final struggle to achieve independence or die trying. He was quickly imprisoned by the British for what amounted to treason. A violent uprising followed throughout India, much of it directed at railway stations, telegraph offices and other British-built communications and transportation posts. To Gandhi's great grief, 1.5 million Indians died in the resulting chaos and famine, and he mourned by fasting for 21 days while under house arrest at the Aga Khan's palace in Poona.

When he was released in 1944, he attempted to engage Jinnah in a dialogue about unified independence, but his vision of a decentralized multi-creed agrarian state was viewed as an anachronism by Jinnah and (with all due respect) by Nehru, and Gandhi was effectively shut out of the negotiations which resulted in the Mountbatten Plan and the declaration of independence of India and Pakistan as separate dominions in August 1947. As Gandhi had predicted, however, violent Hindu-Muslim riots broke out all over India and once again, in an attempt to bring peace, the 78-year old Gandhi fasted. He stopped only when community leaders agreed to do everything they could to stop the violence. Lord Mountbatten later observed that as Gandhi walked from village to village, nursing and consoling the victims of the strife, he came to be "a one-man boundary force" between the Muslims and the Hindus. Radical Hindus, however, became increasingly angry with what they perceived to be Gandhi's constant appeasements; and on January 30, 1948, as Gandhi was on his way to an evening prayer meeting, he was shot at point blank and killed by Nathuram Godse, the editor of an extremist Hindu newspaper.

India, then as now, is nothing like Gandhi hoped it would be, and it is fair to question the extent of his lasting impact there as anything other than a semi-mythical "father of the nation," as Nehru called him. As a philosopher of nonviolence and an endlessly adaptable, abstract global symbol, however, he had an enduring effect on the history that followed, inspiring leaders from distant corners of the world, from

Martin Luther King, Jr. to Desmond Tutu to Natan Scharansky to Greenpeace to factions of the Northern Irish, to name but a few.

Labels: India, Peace Activism