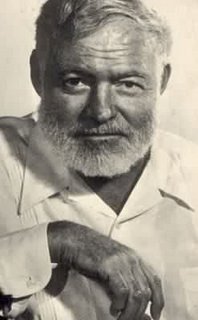

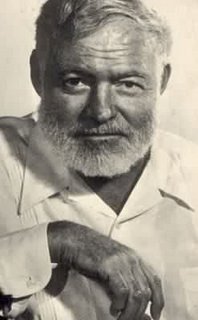

Here was a man with giant mandibles, biting great chunks out of the first half of the 20th century everywhere he went (and he did go almost everywhere) and chewing up forests-worth of newsprint with his gargantuan appetite for self-promotion. Despite being filled with noisy boxing matches, bullfights, safaris, deep-sea fishing jaunts, love affairs, bar binges and the occasional war, Hemingway's life might not be the sort that should have survived in legend -- there were so many contemporary "sportsmen" with disposable incomes competing for immortality in seeming worship of

Teddy Roosevelt's setting the bar for manhood at the turn of the century -- but the manner of Hemingway's self-promotion set him apart. Populating his fiction with thinly-disguised autobiographical portraits and fantasies, he is now considered to be one of the greatest writers in American English.

Yet, perhaps for his chutzpah and his increasingly unpopular machismo, he has been and continues to be maligned by some within the literary establishment for his supposedly guttural, terse writing style -- an unfair assessment of what is often lyrical, understated and rhythmic writing. Hemingway made no bones about acknowledging his debt to journalism, calling his style "cablese," a variation of the prose written by foreign correspondents in transatlantic cables to their home papers: literate, if sometimes staccato, the overall effect being the result of polish rather than decorative elaboration, his aim being to imbue each word with its own equal weight within finely balanced sentences. The Annual "Bad Hemingway" contest notwithstanding, it is very difficult to imitate his style. It is actually much easier to write "bad Faulkner." I do it all the time.

Born on this day in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, Ernest Hemingway was the son of a physician. After high school he moved to Kansas City and briefly worked as a reporter on the

Star, learning the writing lessons from the

Star style guide which would become his artistic credo:

"Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English, not forgetting to strive for smoothness. Be positive, not negative." Kept out of the Army due to bad eyesight, he apparently could not be kept from driving ambulances in World War I, and was seriously wounded at 18, dubbed by the newspapers as the first American casualty in Italy. His experiences recuperating in an Army hospital in Milan , and his affair with an American nurse, formed the basis of his later novel,

A Farewell to Arms, 1929.

He returned to the U.S. as a minor celebrity with a talent for storytelling, and soon caught on as a European correspondent with the

Toronto Star. He plunged headlong into the expatriate community of writers and artists swirling and posing around Paris, befriending some of them, including Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gertrude Stein. With their encouragement, in 1923 he published his first collection of short stories, featuring one of his many alter egos, "Nick Adams," followed by two novels in quick succession:

The Torrents of Spring and

The Sun Also Rises (both 1926).

The Sun Also Rises made him America's star novelist abroad, yet one critic scoffed that it was one of the "filthiest books of the year."

Hemingway's preoccupation with Spain -- particularly with bullfighting -- was revealed in

Death in the Afternoon (1932), but Spain would become more than just a canvas for him. His return to reporting, coincident with the publication of an adventure novel about political commitment,

To Have and Have Not (1937), led him to campaign in sympathy with the Loyalists against Francisco Franco and the fascists during the Spanish civil war: he raised money for them and tirelessly publicized their cause with newspaper reports, a play (

The Fifth Column, 1938) and the most popular of his novels,

For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940). He covered World War II, and settled in Cuba after the War, swimming and fishing and drinking, and writing less frequently.

In 1952, he published

The Old Man and the Sea, the last significant piece he would release in his lifetime, and for it he won the Pulitzer Prize. Two years later, while hunting in Africa, he was severely injured during the crashes of not only his own chartered plane but the plane which came to rescue him, and thereafter suffered from severe headaches and decreasing mobility. A lifetime of other accidents (he seemed to be prone to them), heavy drinking and tough living had also taken its toll on him, leaving him gloomy and increasingly banished from the kind of life he preferred to live. In 1954, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, but was too ill and injured to attend the ceremony. His exile from his beloved Cuba after Fidel Castro's revolution played itself out in Cold War politics between the U.S. and the Soviet Union in 1960 was also a bitter disappointment. He was suffering from extreme depression and had made two suicide threats before, when on July 2, 1961, Hemingway shot himself in the forehead with a shotgun in his home in Ketchum, Idaho.

Since his death, several books have been patched together from his notebooks, including a memoir of Paris during the 1920s (

A Moveable Feast, published in 1964) and the novel

The Garden of Eden (1986). There have, of course, been numerous films based on his works, perhaps the best among them (although not the most faithful to their sources necessarily) being

Howard Hawks' To Have and Have Not (1944, with Bogart and Bacall) and

The Killers (1946, with Burt Lancaster). Understanding that his life had threatened to overshadow his work, Hemingway wrote in 1950:

"I want to run as a writer; not as a man who had been to the wars; nor as a bar room fighter; nor a shooter; nor a horseplayer; nor a drinker. I would like to be a straight writer and be judged as such."

Labels: Journalism, Literature

Baxter Ward -- TV newsman and Los Angeles County supervisor from 1972 to 1980 -- was born on this day in 1919 in Superior, Wisconsin.

Baxter Ward -- TV newsman and Los Angeles County supervisor from 1972 to 1980 -- was born on this day in 1919 in Superior, Wisconsin.