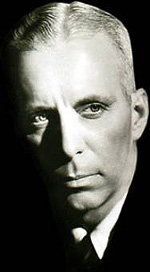

Hawks

Film director Howard Hawks was born on this day in 1896 in Goshen, Indiana.

Raised from the age of 10 in Pasadena, California, Hawks enjoyed a lifelong love affair with speed and man-made machines. He attended Phillips Exeter, obtained his mechanical engineering degree at Cornell, raced cars and planes, and worked during the summers as a prop boy for film studios in Hollywood. Possessed of an exceptional education, a fine taste in clothes, upper-crust manners and a thirst for adventure, he would not stay in the prop room for long.

After a stint as a flight instructor in the U.S. Army Air Corps in World War I, Hawks shared a house in Hollywood with seasoned director Allan Dwan and budding film talent Irving Thalberg, Hawks landed a position in the story department during the early 1920s at what was to become Paramount Pictures. His work with Paramount sufficiently impressed William Fox, who invited him to direct films just as the silent era was ending.

Hawks' first sound film, The Dawn Patrol (1930, with Richard Barthelmess and Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.), was a successful mix of action-packed aerial stunts and believable, fast-paced dialogue -- the latter being a hallmark of all of Hawks' films, in that he always tried to cast intelligent actors who were capable of riffing around the written dialogue. His Scarface (1930, with Paul Muni and George Raft; produced by fellow airplane-addict Howard Hughes and written by Ben Hecht, Hawks' frequent collaborator) is considered to be one of the most violent gangster movies of the 1930s (modeled on the life of Al Capone), as well as one of the wittiest and most entertaining.

Many of Hawks' films seemed to center on male friendship, and his foray into the "screwball comedy" genre beginning in the 1930s (typified by Twentieth Century, 1934, with John Barrymore and Carole Lombard; Bringing Up Baby, 1938, Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant; and His Girl Friday, 1940, with Grant and Rosalind Russell) seemed to bring along with it the notion that men and women could be friends as well as lovers, another periodic theme in Hawks' work.

During World War II, Hawks directed Humphrey Bogart in two of his greatest films. To Have and Have Not (1944) was the result of a bet between Hawks and his drinking buddy Ernest Hemingway that Hawks could not make a good movie out of Hemingway's worst novel. Hawks hired William Faulkner to help with the screenplay, brought along a teen magazine model phenom discovered by Hawks' wife for the female lead (who turned out to be Lauren Bacall), and won the bet. In The Big Sleep (1946), Hawks expanded upon the Bogart-Bacall fantasy through a witty adaptation of Raymond Chandler's labyrinthine novel.

The final two decades of Hawks' career were devoted mostly to John Wayne vehicles -- Red River (1948), Rio Bravo (1959, with Dean Martin as the drunken cowboy), Hatari! (1962), El Dorado (1967) and Rio Lobo (1970). Hawks also produced the seminal sci-fi flick The Thing (1950). He was celebrated during the 1950s by Francois Truffaut and other European critics as one of the great Hollywood directors who managed to rise above the Hollywood factory condition to display a consistent cinematic style over many years, a model auteur of American cinema. The ubiquitous "buddy/cop" films of the 1990s owe a debt to Hawks, but are pale echoes; of late, I would venture to say, the most faithfully Hawksian items on the planet, in both form and substance, have been on TV, in such vehicles as Aaron Sorkin's Sports Night (1998-2000) and West Wing (1999-2006), as well as in the projects of Sorkin's imitators.

Hawks died on December 26, 1977 in Palm Springs, California.

Labels: Classic Cinema

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home