State v. Pearce 'What's the Use' Chiles, Part III

See Part I.

See Part II.

El Paso's first ever Mid-Winter Carnival opened on January 16, 1901. Miss Claire Kelly presided as Carnival Queen, with a court of twelve Maids of Honor, while attractions at the Carnival included an electric fountain; Lunette, the Flying Lady; Bosco, the Snake Man; a simulated volcanic eruption; roping, tying and rough riding contests; confetti and serpentine battles; and bullfights daily, just across the border in Ciudad Juarez.

People came from miles around to attend the Carnival, which of course drew all manner of commercial exhibitors, jugglers, acrobats and street entertainers. Also on hand were the usual bunch of thieves, con-men and pickpockets who could always be counted on showing up wherever there were big crowds. Pearce Chiles was there, too. We will never know what mischief he got into at the Carnival (he seems to have paid a $101 fine for some infraction there), but we have some idea of what he hoped to accomplish after it was over. What we do know comes from the official court records of Chiles' case.

On an eastbound train, the G.H. Limited, rolling through southern Texas and heading for Hot Springs on the evening of February 15, 1901, Chiles and his faceless companion, a D.B. Sherwood, spotted a young, recently discharged soldier, a fellow named Benjamin F. Henry from Albany, Georgia, and thought they had found an easy mark. According to Henry's testimony, the affable Sherwood struck up a conversation with Henry, and was soon sitting next to him for the ride. A while later, Chiles came down the aisle, stopping at Sherwood's shoulder and asking him for a light for his pipe. Sherwood pulled out a matchbox and handed it to Chiles. Chiles feigned difficulty opening it and protested to Sherwood. "What are you trying to do?" he asked. "Poke fun at me?" Sherwood insisted that there were matches inside the box, but Chiles still couldn't open it, finally handing the box back to his accomplice, declaring, "I can't open it, and nobody else can, either. I will bet you $50 or any amount of money that he," referring to Henry, "can’t open it." Sherwood leaned over and whispered to Henry, "How much money do you have? Bet it and we will win." Henry demurred, but Chiles kept the con alive, betting Sherwood $5 and saying, "I'll pay this man a dollar for every dollar in his pocket if he can open the box."

Sherwood handed the box to Henry, who opened it without difficulty. Chiles said, "All right. I am an honest man. I pay every time I lose." "Pay him $5," Sherwood said, pointing to Henry. "No, I won't," said Chiles. "He hasn't got any money on his person." Henry then admitted that he had $95 in his pocket. As Henry got his money out to show Chiles, Chiles and Sherwood engaged in a little pretend argument over the bet, and in the ensuing confusion, Sherwood got a hold of Henry's money. The thieves disappeared out of the coach, but Henry managed to raise the conductor and the brakeman, and before long, Chiles and Sherwood were in the custody of a state ranger.

In jail awaiting trial in El Paso, Chiles reached out to the folks who had always been able to help him in the past – his baseball compatriots. According to George Girsch, writing in the August 1958 issue of Baseball Digest, Chiles wrote a letter to one of his friends in Philadelphia. How Girsch got his hands on this letter, and where it is today, I do not know, but it reads in part:

"Friend Billy,

i taught that i would right you in regards to what happened to me while on the train i left this town on my way to hot Springs last friday night and while on the train a man had a match box which is hard to open so i bet him he could not open it while i counted on my fingers so i won and he had me arrested . . . so i dont know any body hear and hafto stay in jail this man told all kinds of lies and did not tell the truth at all So i want you to goe and get some good men to right to this Prosecuting atorney and tell him that I aint no theift . . . Dont let them put it off for this is a Bad country to have trouble in . . ."

Neither his friends nor the Phillies came to his aid. For a time, Chiles banked on the idea that Benjamin Henry would not return to El Paso to appear as a witness against him. When he later heard that Henry had arrived and had already testified at Sherwood's trial, he thought people were kidding with him; but after the news of Sherwood's conviction, Chiles folded, and according to the El Paso papers, pleaded guilty. The report from the sports pages read:

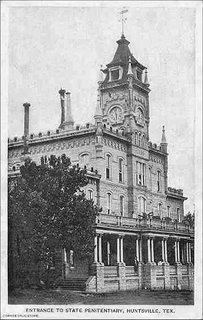

"Pearce Chiles, the famous coach and buzzer manipulator of the Philadelphia club, is now lost in the sea of despair. He has signed a new contract, but not for any $2400, nor will any American League team try to steal him away from his new employers. Chiles is to do two years on the Huntsville convict farm, and his uniform will be back and white, with the number 24876 across his back. He will not stop at the Fifth Avenue Hotel, but will sleep in an abandoned hog pen, and his daily menu will include sour bacon, hominy, corn bread and pure water. Incidentally, Chiles will be allowed to work from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., and the work will be so different from that of last year that it will be an interesting novelty . . . Such is the fate of Pearce Chiles. How this man ever got on the Philadelphia team is a mystery. He was run out of Kansas and Texas years ago for serious crimes, and now gets the two-year trick for working a flimflam game."

My inquiry with the Texas Department of Corrections yielded no details of his escape from the Huntsville Prison on August 19, 1902, after serving less than sixteen months of his sentence. An administrative assistant wrote, "The above referenced individual was received from El Paso county, Texas for Theft of Person a 2 year sentence. Due to the age of this information that is all the information available to us. We are sorry but this is all the information we are allowed to give."

He apparently had the chutzpah to play a stint with the Natchez Indians in the Cotton States League at the end of the 1902 season. After that, it seems that the slippery con-man made his way to Portland, intending to play for the Portland Browns club in the Pacific Coast League, but he was quickly dismissed from the team in February 1903 after getting arrested for an alleged assault on a young woman named Roe. As Sporting Life reported the incident, "Chiles struck her in the face, blackening her and loosening her teeth." Today, Portland doesn't seem to have any record of the incident. The following month, Pacific Northwest League president W.H. Lucas strenuously denied that Chiles had been signed by the League’s San Francisco club, declaring that “Chiles will never be permitted to play in the Pacific Northwest League so long as I am president of it.”

Later in 1903, Chiles was playing for Fortuna, a semi-pro club in a one-horse northern California town. After that, he seems to have disappeared.

Leave it to the larcenous fellow to cover his tracks so well. Did he flee to Canada? Or Mexico? Did history intervene, leaving him an unidentified victim of the San Francisco earthquake or the sinking of an ocean liner? Or did he just fade away -- like thousands of roving oddjobbers, good and bad ones alike, without roots or loved ones? It's possible we won’t ever know the final chapter of this strange, sad little story.

[With helpful correspondence from Joe Dittmar.]

Labels: Baseball, Cups of Coffee, Pearce Chiles, Works in Progress

2 Comments:

Chiles possibly changed his name to Newton Chiles, moved to Los Angeles and died there.

His son was named Alfred, same as our mans father and he was born in Deepwater, Mo same as our man. Accd to his Death Certificate.

Nothing is for sure regarding Chiles. But before the 1910 census no Newton Chiles exists in he Census.

I am aware of Newton B. Chiles as a candidate, and I've done a bit of my own research.

On the California Death Certificate of Newton Chiles' son, Alfred Barron Chiles, Alfred's father's name is listed as "Newton Barron Chiles," born in Missouri.

Although I wouldn't put it past an incorrigible con-man to go to great lengths to hide his real identity, I do find it strange that if "Newton Barron Chiles" was "Pearce Nuget Chiles," that he would have given his son his own made-up middle name. But you never know.

Until better evidence appears, I remain skeptical about Newton Chiles' identity as Pearce Chiles.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home