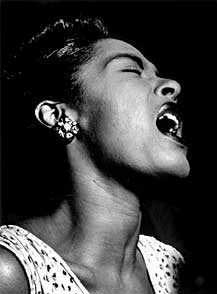

The Lone Wolf and his Instrument

"Bechet was an individualist, a lone wolf, the sharp who blows into town, cleans out the locals, and disappears again." -- J.L. Collier.

One of the great traditional New Orleans jazz artists, Bechet's style was nevertheless wholly his own, as singular in some ways as his nomadic, solitary career. Born on this day in 1897 to African-American Creole parents (although his mother was light-skinned enough to occasionally passeblanc), Bechet learned to play clarinet by practicing on his older brother's instrument when no one was looking. At 13, he was already playing professionally, and the following year, he began his life of wandering.

In 1918 he was in Chicago, then in New York, and in 1919 he was in Paris with Will Marion Cook's band, where he caught the attention of conductor Ernest Ansermet, who gushed: "There is in the Southern Syncopated Orchestra an extraordinary clarinet virtuoso who is, so it seems, the first of his race to have composed perfectly formed blues on the clarinet . . . I wish to set down the name of this artist of genius, as for myself, I shall never forget it -- it is Sidney Bechet . . . who is glad one likes what he does, but who can say nothing of his art save that he follows 'his own way' . . . perhaps the highway the whole world will swing along tomorrow."

Ansermet proved perceptive at least about Bechet's personality: he was a loner who went his own way, symbolized neatly by his 1941 overdubbed novelty recording of "The Sheik of Araby" in which he played all of the instruments by himself, including bass, drums and piano. Bechet became the most important jazz artist in Europe, playing with astonishing inventiveness, verve and his signature shimmering vibrato style in various groups in Paris and London, where he also took up the soprano saxophone, still a novelty in 1920. He was the first saxophonist of any consequence in the history of jazz.

At the same time, he was demanding and hot-headed, making him difficult to work with, and he occasionally ran afoul of the law: he was deported from London following a fight with a prostitute and imprisoned in France for 11 months following a gunfight with another musician outside a Paris cabaret. Back in the U.S., Bechet began his recording career, soloing with Clarence Williams Blue Five and the Red Onion Jazz Babies (featuring Louis Armstrong). Despite Armstrong's own virtuosity, Bechet dominated their recording of "Cake Walkin' Babies" (1924), showing a mature command of the still-developing rhythmic "swing" of jazz.

After spending the early 1920s back in the U.S. (where he also worked stints with Duke Ellington and James P. Johnson, had a brief affair with Bessie Smith and launched the career of Johnny Hodges), Bechet sneaked back into Paris with La Revue Negre (with Josephine Baker) in 1925. He promptly left the show, however, to tour Russia and Germany, and slowly slipped into obscurity, buried in Noble Sissle's orchestra.

During the late 1930s, as small-band jazz was in collapse, Bechet enjoyed a comeback with a hit recording of Gershwin's "Summertime" (1938), followed by "Wild Man Blues" (1940), a traditional New Orleans piece which he elevated with his own timeless invention; a transcendent masterpiece of slow jazz variations, "Blue Horizon" (1944); and "Les Oignons" (1949), a million-seller in Europe. Bechet had by this time returned to Paris (with some trepidation, given his history there), but he was welcomed as a hero, and lived there until his death, on this same day in 1959. He posthumously published a frank autobiography, Treat it Gentle, in 1960.