"The Tramp is as centrally representative of humanity, as many-sided and mysterious, as [Shakespeare's] Hamlet, and it seems unlikely that any dancer or actor can ever have excelled him in eloquence, variety or poignancy of motion."

"The Tramp is as centrally representative of humanity, as many-sided and mysterious, as [Shakespeare's] Hamlet, and it seems unlikely that any dancer or actor can ever have excelled him in eloquence, variety or poignancy of motion." -- James Agee.

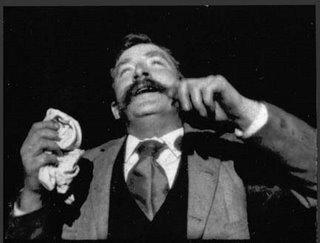

The man who once had the most recognizable face on Earth and gave joy to millions of moviegoers began life much like a waif in a Dickens novel: born on this day in 1889 in London to a pair of unstable music hall performers, Charlie Chaplin spent most of his childhood in public charity houses and on the streets. Brought to London by stage actor William Gillette with his tour of

Sherlock Holmes in 1905, Chaplin eventually joined Fred Karno's vaudeville troupe and soon became its star attraction, known around England and America for his "comic drunk" sketches. On his second tour of America, Mack Sennett offered Chaplin a film contract, and Chaplin accepted.

Initially puzzled by film continuity, for one film he continued in the Sennett tradition of knockabout comedy with very little pause for character development. Beginning with his second film,

Kid Auto Races at Venice (1914), however, Chaplin wore a small moustache, bowler hat, baggy pants borrowed from Fatty Arbuckle and floppy shoes, twirled his walking stick and began to create a new comic character, the "Tramp."

In shorts made for Keystone (some co-starring Mabel Normand) and later Essanay, Chaplin framed his scenes to enhance the audience's connection with his "Tramp" and slowed the action slightly to permit flashes of social and psychological observation amidst the chases and cartoon brutality. The Tramp also had the ability, it seemed, to animate the inanimate, waging a protracted and very personal battle against a saloon door or carrying a running conversation with a statue of a female nude. With his graceful manner belying his tattered clothes, and his compassion for the meek, he was an outsider in the world of silent comedy -- but Chaplin also set up his character as a social outsider within the stories in his films. In shorts such as

The Tramp (1915), he typically enters bourgeois society by providing assistance to a soul in distress (often Edna Purviance), beats off the villains, dreams for a moment of settling down with Edna, but is always reminded of his poverty and, blithely, moves on to his next adventure.

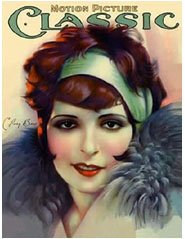

Chaplin's popularity, matched for a time only by that of

Mary Pickford, reached heights not previously known in the history of cinema: audiences around around the world awaited his next film with anticipation, and nickelodeons had only to put up his picture with a sign saying "I'm here today!" to attract long lines.

He moved from Essanay to Mutual, bringing along his own little company of players and technicians (Purviance, the leviathan Eric Campbell, cameraman Rollie Totheroh), and made a dozen brilliant two-reel comedies (including

The Immigrant,

The Rink and

Easy Street) which are warm and hilariously funny pieces of cinema.

In 1918, he signed a $1 million contract with First National, during which he gradually transitioned from short films to features, culminating in his most ambitious film to date,

The Kid (1921, with little Jackie Coogan), combining Victorian melodrama with beautifully choreographed sight gags.

Chaplin joined other members of "Hollywood royalty," Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and

D.W. Griffith, in establishing United Artists (UA) in 1919, and preserved for himself complete control over his work for the rest of his life. (He even went so far as to compose his own film music -- including two hit songs, "Smile" for

Modern Times, and "Eternally" for

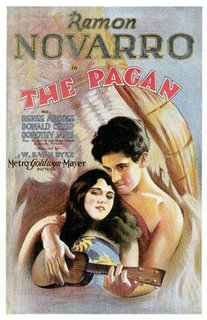

Limelight.) For UA he made his last 4 silent films --

The Gold Rush (1925),

The Circus (1927),

City Lights (1931) and

Modern Times (1935, with some sound sequences, made 7 years after talking pictures had arrived) -- each of them classics containing elements of his earliest work (the Tramp's pluck and essential alienation), developed on a grander scale, resulting in some of the most memorable moments in cinema: the Tramp eating his own shoe in

The Gold Rush, the famous ending shot of Chaplin in

City Lights during which the flower girl who has regained her sight suddenly recognizes him, and the ending scene of

Modern Times, in which the Tramp finally goes off into the sunset with the girl (his third wife Paulette Goddard).

Agonizing over how to permit his Tramp to join the world of talking cinema, Chaplin seized upon the Tramp's superficial resemblance to Nazi dictator Adolf Hitler, and made

The Great Dictator (1940), playing upon the prevailing American opinion of Hitler, prior to his exposure as a genocidist, as an anti-Semitic clown.

During the 1940s, Chaplin became the target of J. Edgar Hoover and other anti-Communists who were suspicious of his leftist leanings and his apparent support of the Russian second front during World War II. A sexual adventurer, Chaplin was an easy target, and the FBI helped to trump up a paternity case against him through the cooperation of a former lover of his, an unstable aspiring actress named Joan Barry, in 1943. Genetic evidence, excluded from the trial, proved that Chaplin was not the father of her child, but a jury tagged him for support. Meanwhile, at age 54 Chaplin married Oona O'Neill, the 18 year-old daughter of playwright Eugene O'Neill. After being refused admission to the U.S. on the grounds of his "unsavory reputation" following a European trip in 1952 (again the work of Hoover, whose file on Chaplin was 1,900 pages long), Chaplin and Oona settled in Switzerland.

He continued to make films sporadically until 1967 (working with such talents as Claire Bloom, Marlon Brando and Sophia Loren). In 1972, he made a triumphal return to the U.S. to receive a special Oscar (despite Hoover's lobbying against giving him an entry visa), and in 1975 he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II. He passed away on Christmas Day, 1977 in Vevey, Switzerland.

Richard Attenborough made a not half-bad biopic of Chaplin's life,

Chaplin, starring Robert Downey, Jr., in 1992.

Labels: Silent Film