The Good Badman

William S. Hart (born on this day in 1865 in Newburgh, New York) grew up in the Old West of Jesse James and Wild Bill Hickok. His father moved the family West from New York, ultimately to the Dakotas, where young Bill Hart had Sioux Indians as childhood playmates. Hart developed a deep affection for the culture of the Old West, even as he watched it fade. Yet the lure of the theater took him East, where he became a respected Shakespearean performer, and originated the role of "Messala" in the first stage version of Lew Wallace's Ben Hur in 1899.

At the unlikely age of 49, William S. Hart moved to Hollywood and entered films as a cowboy hero in 1914.

He had caught his first glimpse of what passed for a cowboy movie in a nickelodeon in New York. Hart was appalled by most Western movies of the day, regarding them as silly caricatures of a great frontier tradition. With his own first-hand knowledge of what the West was like, strong athleticism despite his age and a sure sense of horsemanship -- in his own films, Hart sought to portray what he regarded as the true values of the West: the endurance of hard physical work, a responsibility for protecting the weak, and a respect for the land. Through his work, the Western came of age.

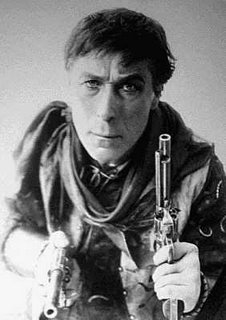

Hart's unforgettable face -- like a sad-eyed, weather-beaten totem pole carving -- helped advance his persona as the strong, silent hero who dispenses justice without compromise, the "good badman" whose mythic status later resonated through the screen personae of actors such as John Wayne and Clint Eastwood.

As it turns out, Hart's Westerns -- such as The Bargain (1914), The Disciple (1915), Hell's Hinges (1916), The Narrow Trail (1917) and his masterpiece, Tumbleweeds (1925) -- were among the finest films of any genre made during the silent era. Often, with Hart's emphasis on authentic locations, costumes and sets and authentic Old West dust hanging in the air, one has the feeling that one is watching an ancient daguerrotype coming to life. Hart's photoplays were usually about the moral awakening of his protagonists -- the hard-bitten lone wolf, whose ethical sense blooms in the aftermath of an impromptu good deed or upon meeting a chaste heroine -- and while his films were not known for their action sequences, there is a certain transcendental feeling to those moments when Hart might speed across a prairie on his horse.

He made 65 films in 11 years before calling it quits at age 60 -- reemerging only once, in 1939, to film a short prologue for a re-release of Tumbleweeds, the one and only sound record of Hart's Shakespearean style and diction. Upon his death on June 23, 1946 in Newhall, California, he donated his 22-room, 265-acre Horseshoe Ranch to Los Angeles County. Today, it comprises the William S. Hart Ranch and Museum, and it is home to an extensive collection of Western art, as well as numerous grazing animals, including a small herd of bison donated by Walt Disney Studios in 1962.

Hart's autobiography, My Life East and West,

Labels: Old West, Silent Film

3 Comments:

You have captured my dad's cowboy hero. No wonder he viewed Roy Rogers as a pretender, given his Ohio background and accessories.

Can you tell me where in the Dakotas the Hart family lived? Thanks...

During their years in the West, the Harts were essentially nomads, as William's father, Nicholas, made his career setting up grist mill machinery. At various times throughout William's childhood, the Hart family put down shallow stakes in Illinois, Iowa, Wisconsin, Minnesota and even the Dakota Territory, where they lingered just prior to the fateful battle at Little Bighorn. Hart maintained that his best friends all along the way were Indian children, and he apparently encountered Sioux as far East as Minnesota. Nicholas Hart ended up sending his family back East when William was a teenager, and returned to New York himself shortly thereafter -- a "failed pioneer," as editor Martin Ridge has written.

So, it is fair to say that the Hart family breathed on the Black Hills, but didn't stay long enough to leave their imprint there. But the West certainly left its imprint on young William . . .

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home