Woman in the Counting-House

"(Women) are on trial. They feel they must do twice as much as is demanded of them to hold their own in the world they have set out to conquer." -- Natalie Schenck Laimbeer.

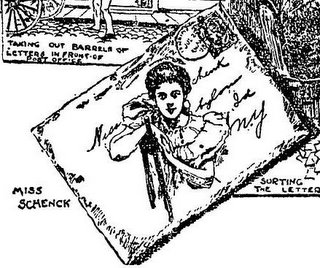

Born to a socially prominent Brooklyn-Long Island family on this day in 1882, Natalie Schenck was schooled in working for charitable and educational causes at an early age. When she was 15, she collected $25,000 in dimes (that's 250,000 dimes, folks!) for an American Red Cross Cuban relief effort through a highly-publicized chain letter program. Her efforts also resulted in the little post office at Babylon, Long Island getting choked with mail.

Natalie eloped with the dashing Capt. Charles Glen Lee Collins of the British Army in 1904, but soon after giving birth to their son they were divorced. Collins, it seems, was under the impression that Natalie's father was wealthy, but although Spotswood Schenck was long a fixture on Wall Street, he was merely moderately provisioned. (Collins was later a wanted man on theft and forgery charges, and left debts of nearly a half million dollars in his wake.) In 1909, Natalie married William Laimbeer, a Wall Street banker, and in 1912, while raising 2 new daughters and her son, she became manager of the Bureau of Home Economics of the New York Edison Company, giving public lectures on the benefits of electricity in the kitchen. In 1913, she and her husband were in a terrible auto accident -- Laimbeer's car was struck by a Long Island Railroad train, killing William and two other passengers, and leaving Natalie severely injured.

Despite her injuries and the loss of her husband, proving yet again her extraordinary energy, during World War I she volunteered for the U.S. Food Administration (headed by Herbert Hoover) devising plans for canning food. Although William Laimbeer had left her in a financially stable situation, she desired more for her children, and in 1919, in her first wage-earning position ever, she entered the male-dominated world of Wall Street herself as manager of the U.S. Mortgage and Trust Company's "women's department," the division of the bank responsible for the few female clients of the bank.

Although the move was primarily a marketing effort, Natalie Laimbeer proved to be a sharp and efficient administrator, and within 6 months she was promoted to assistant secretary in charge of setting up the women's departments in a number of U.S. M & T's Manhattan branches as a new era of financial services tailored for women began to emerge.

In 1925, Charles E. Mitchell at National City Bank, Wall Street's largest bank, offered Laimbeer the position of assistant cashier, the first executive position National City ever offered to a woman. While the New York Times realized her achievement was significant and gave it some coverage, it chose to focus on her chosen interior decoration for her office rather than on her skill as a banker. Soon afterward, Laimbeer founded the Association of Bank Women to nurture the advances made by her female peers at other banks.

Poor health led to her retirement from National City in 1926, but in the 2 years prior to her death she also kept her hand in Wall Street as the financial editor for The Delineator and a contributing writer to the New York World. She passed away on October 25, 1929, the day after the "Black Thursday" that signaled the beginning of the Stock Market Crash of 1929.

Labels: Business and Finance, Trailblazing Women

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home