The Scrapbook Mind of Laurence Sterne

"He had a scrap-book mind that collected diverting information regardless of its importance or its source." -- J.A. Work.

Laurence Sterne (born on this day in Clonmel, Tipperary, Ireland in 1713) took London and the literary world by storm in 1760 with the publication of the first two volumes of his ground-breaking book The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy

He was the son of an English Army officer and lived his early years as an Army camp-follower. He went to Jesus College, Cambridge, following in the footsteps of his uncle (an Archdeacon of York) and his great-grandfather (an Archbishop of York). As he left Cambridge, the image he conveyed was one of an odd, unfocused man, tall and lean as a skeleton, pallid, without an ounce of harm in him -- a young fellow who had talent but was prone to misapply it.

One morning shortly after college he awoke to find his bed full of blood, the victim of a burst blood vessel in his lung -- an event which gave him a lifetime's fear of death hovering around the corner. Broke and unable to decide on a career, he entered the church, principally to take advantage of his family's contacts for preferment. For a time he roamed the city of York as a bachelor preacher and noted social wit, until marrying and settling down as the dilettante vicar of the sleepy Yorkshire villages of Sutton on the Forest and Stillington -- one who preferred painting, fiddling, farming and hunting to studying the scriptures. His rash enthusiasm with the absurd and the mildly bawdy led him to take up Luke 5:5 as his text for a sermon the week following his marriage -- "We have toiled all night," goes the verse, "and have taken nothing."

Though emotionally volatile and sentimental to the point of being considered "crack-brained" by his neighbors, his rhetorical skills made him a capable preacher and political operator. His flirtations with politics indirectly led him to write Shandy: in 1759 he wrote a political satire directed at a local church lawyer, The History of a Good Warm Watch-Coat, which he subsequently withdrew from publication because it might have proved embarrassing to the church in Yorkshire. Nonetheless, the reactions of his close friends to the work led him to believe he might be a writer, and he quickly began to scribble away at Shandy, publishing the first volumes in 1760, with subsequent volumes appearing until 1767.

There had been nothing like it: bastardizing John Locke's theory of the "association of ideas" as a rhetorical device, Sterne's narrator roams blithely from the history of fortifications to art theory to musical notation to reflections on Biblical tales, Shakespeare and Cervantes (he also drew heavily upon themes from Rabelais and Robert Burton) while ostensibly telling the story of the moment of his own conception -- a chronology which barely advances over several volumes -- occasionally employing such ludicrous, unorthodox devices as a misplaced preface, irregular typography and a missing chapter.

While Sterne became the celebrity of the moment in London society, a gangly, charming country preacher who had authored an irreverent book, he had his share of critics: Samuel Richardson, no doubt smarting over Sterne's veiled satire of Richardson's newfangled novels of morality, indicted Shandy as "incoherent" and "indecent"; poet Oliver Goldsmith similarly condemned the work as "bawdy." While resting in Europe for his health, Sterne wrote a memoir of his travels thinly disguised as a tale involving his fictional alter ego, the preacher Yorick, A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (1768), his only other significant composition. Sterne died at age 55 on March 18, 1768.

Tristram Shandy, long loved as a work of literature but generally considered unfilmable, is the basis for a film by the controversial director Michael Winterbottom, released in time for the recent Toronto Film Festival; though I have not seen it yet, I note that in general the critical response has been one of bewilderment. No doubt that would have pleased Sterne as well.

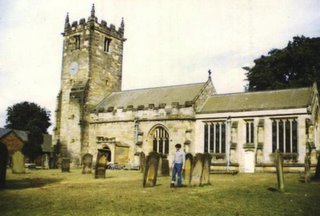

Seen below is yours truly, taking time out from a day's cycling in the fall of 1983 to visit Sterne's grave at Sutton-on-the-Forest in Yorkshire, England.

Labels: Literature

2 Comments:

Just a tiny correction post - the church is Coxwold not Sutton-on-the-Forest.

A Clarification: The photo above is indeed a photo of me loitering in the graveyard at Sterne's former parish church at Sutton-on-the-Forest, taken in 1983. I think I had arrived there fully expecting that I would probably find Sterne's grave, but I was clearly misinformed on that point; and the thrall of my memory of that day has gotten the better of my usual attention to detail.

There are now, in fact, two places in England that can lay claim to Sterne's remains -- and neither of them is Sutton-on-the-Forest. As my anonymous reader points out above, Sterne's final parish at Coxwold claims to have buried in its yard a fragment of Sterne's head, and has a stone to mark the presence of the alleged relic.

Sterne was, however, originally buried in an unmarked grave in St. George's burial ground, at Hanover Square in London. Rumours of the robbery of that grave almost immediately sprang up, ultimately coalescing in the story that Sterne's corpse was later discovered in a university anatomy lab.

The writer David Thomson observes that (1) Sterne's grave was unmarked until a subsequent stone was erected, pointing out that Sterne was buried "near to this place," and (2) the fact that the handlers of his literary estate fomented the grave-robbing rumours, with an eye toward using the publicity to sell more books, calls into question the authenticity of the grave-robbing tale. Both observations would seem to suggest that it is difficult to substantiate that Sterne's body was removed from St. George's in a way that it would ever find its way to Coxwold -- if it was removed at all. Furthermore, according to Thomson, the secretary of the Sterne Trust was, as early as 1968, only "reasonably sure" that Coxwold had Sterne's actual head.

I don't wish to apologize for my faulty memory of that Fall day in 1983 in Sutton-on-the-Forest, but I do wish to suggest that loitering there and remembering Sterne is about as good as it gets, pilgrimage-wise. If we can't be sure he lies in Coxwold, and we can't be sure he lies in London, then we can't be sure he lies anywhere in particular. Cross yourself, travelers, and toast the man. Alas, poor Yorick!

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home