State v. Pearce 'What's the Use' Chiles, Part I

Ask anyone. I've spent thousands of hours -- poring over pages of microfiche; tracking down gravestones in unmapped graveyards; cold-calling innocents from the phone book; examining dusty, brittle books in dark, unloved corners of libraries from California to New York; and cajoling corporate PR flacks – all in the service of researching the biographical details of dead Americans about whom most living Americans could really care less.

I do have my standards. Usually my targets are pioneers of some kind, first-movers within a budding social, political or cultural institution who've been unjustly neglected by the keepers of the canon.

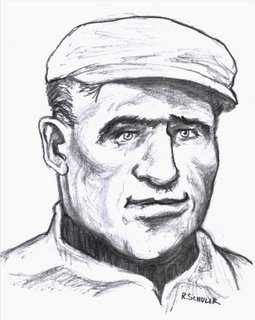

But not Pearce Chiles. Pearce Nuget Chiles was a ne'er-do-well, a scoundrel. A decent enough ballplayer, but a scoundrel. In two partial seasons with the Philadelphia Phillies (1899-1900), he was a late-inning pinch hitter whose lifetime at-bats to runs-batted-in ratio rivals that of Joe DiMaggio (22.04 to Joe’s 22.53) and a thoroughly disruptive baserunning coach, known for his devilishly ingenious system of stealing catcher's signals by employing an electric buzzer device hidden in a mud puddle in the third base coaching box. And as the late Lee Allen (organized baseball's Vasari in Florsheims) came to find before me, Pearce Chiles is one the most slippery, elusive historical characters major league baseball has ever produced.

First, there's the problem of nomenclature. Around the same time Pearce Chiles was knocking around from one minor league club to another, there was a flashy second baseman playing in Cleveland called Clarence Algernon Childs, better known as "Cupid." Cupid Childs should be better known today than he is – he retired with a higher on-base percentage than any second baseman in the Hall of Fame except Rogers Hornsby and Eddie Collins. However, Hall of Famer Christy Mathewson was guilty of careless conflation when, in his book Pitching in a Pinch (1912), he accuses the innocent Cupid Childs – not Pearce Chiles – of the sign-stealing scheme.

If that weren't bad enough, the year after Pearce Chiles "retired" from the Phillies, a utility player named Pete Childs made his debut in St. Louis, and quickly flamed out. Sportswriters of the period were understandably flummoxed, interchangeably referring to Pearce Chiles as "Pete Chiles," "Pete Childs" and, occasionally, "Pierce Chiles," "Pearce Childs," or "Pierce Childs."

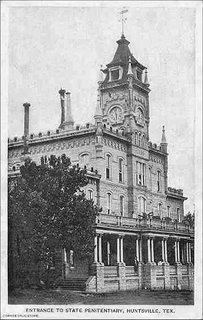

Then there's his retirement. For a number of years, Lee Allen had the last word on Pearce Chiles. At the end of his research file on Pearce Chiles, there was a one-page form letter with typed interlineations from the Texas Department of Corrections, dated May 18, 1967. Regarding "CHILDS, Pierce, TDC #20498 (Active)," the Department informed Allen that "The subject was received in this Institution on June 22, 1901, from El Paso County . . . [and] was dXXXXXXd escaped from the Texas Department of Corrections on August 15, 1902." That was the last trace of him that Allen was able to find. The Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia, long the standard reference work on major league baseball, lists Pearce Nuget Chiles' status as "Deceased" in lieu of giving a definitive date and place of death – a good guess, but an unconfirmed fact.

All scoundrels have parents, the families who spawned them. Pearce Nuget Chiles was born on May 28, 1867 in Deepwater, Henry County, Missouri, the fourth child and only son of Alfred M. Chiles and his wife, Amanda Rutherford. There were Chileses all over Henry County, having decamped there from Virginia. Unfortunately, Pearce's father died when Pearce was 8 years old. Pearce received $325 in the will. By the looks of Pearce's later behavior, it appears that his poor mother Amanda and his older sisters Martha, Anna and Lilley were no match for Pearce's . . . exuberance.

Although the exact date has as of yet eluded me, Pearce Chiles entered organized baseball, probably in his late teens. Unlike some ballplayers of the 19th century who tended to ply their trade near home, Pearce seems to have thought nothing of traveling far and wide, playing for one minor league club after another. By 1895, a reporter in Phoenix was referring to Chiles as a "crack ballplayer." Unfortunately, however, the article was a crime report.

Chiles must have returned to Deepwater for his mother’s funeral (she passed away on July 10, 1895) and gotten into some mischief. Having arrived in Phoenix in the Fall for the Winter League, word reached him that the authorities were after him. According to the February 11, 1896 article in the Los Angeles Times, Chiles "was wanted in Missouri for illicit relations with a sixteen-year-old girl there. As the age of consent in that State is eighteen years," the article went on, "the charge against him is constructive rape." Chiles, however, got the jump on the local authorities, and lit out of Phoenix just ahead of the arrest papers.

In the Summer of 1896 he had been signed to play in Hartford, but I've never confirmed that he made it there. He seems to have played in Galveston in the Texas League during this period, by then having acquired an unusual nickname. His habit of taunting opposing batters when they hit their pop-ups to him by shouting "What's the Use?" before stylishly catching the ball encouraged sportswriters to call him "Pearce 'What's the Use' Chiles," or sometimes, "Pearce 'It's No Use' Chiles." He wasn’t shy about adding insult to injury, and reporters noted that he often found himself in trouble with local authorities, but managed to get out of trouble on the goodwill of his baseball compatriots.

See Part II.

Labels: Baseball, Cups of Coffee, Heroic Tales of Research, Pearce Chiles, Works in Progress