Camerado, This is No Book

"Like Ravel's Bolero and Botticelli's Birth of Venus, [Leaves of Grass] . . . has long been a high-end aphrodisiac." -- N. Gillespie.

When it was revealed in the midst of the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal that President Clinton had given young Monica a copy of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass as a gift, literate America smirked and giggled and knew exactly what was up: ripe Bill had developed one suggestive, broad-shouldered, bare-chested, musky, sun-tanned calling card for himself. He had also apparently given a copy to Hillary when they were courting.

At a time when English poetry could be perceived to have been bred in an atmosphere of relative confinement, on a cramped island, within cramped drawing-rooms and cramped clothing, Whitman's poetry was self-consciously exposed, bathing nude like the woman in Manet's Dejeuner sur l'herbe in the open air of the great Western continent, nurtured by political liberty and expectant of democratic destiny. And people who were never all that comfortable in broad daylight were disquieted by what he wrote.

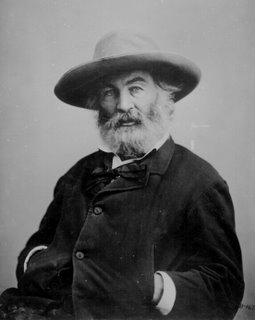

Walt Whitman was born on this day in 1819 in West Hills, Long Island, New York. He grew up in the cramped quarters of Brooklyn, left school at 13 to continue his education in print shops and newspaper offices (as editor, for instance, of the Brooklyn Eagle, a Democratic paper, until his support for the abolitionist Free Soil Party got him fired), and aspired to become a writer. He took a furtive step toward a writing career with a sophomoric romance about the evils of alcohol; but after moving to New Orleans to accept a job with the Crescent in 1848 for just two months, he was reborn as a writer.

After breathing in the sultry, heavy air of the Mississippi delta, he returned to Brooklyn, took up carpentry and began the first edition of his life's work, Leaves of Grass, first self-published, anonymously, in 1855. Not simply a book of 12 poems, Whitman styled the collection as an autobiography of sorts ("Camerado," he wrote, "this is no book/ Who touches this touches a man"), but one in which the universal myth of Whitman, rather than the reality, is composed. In poems such as "I Sing the Body Electric" and "Song of Myself" he celebrates the beauty of the human body and sensual experiences -- his own and others' -- "turbulent, fleshy, sensual, eating, drinking and breeding."

The book was roundly criticized by the literary establishment for its unorthodox form (rhythmic lines, drawn from his studies of music and conversation, within which the traditional concepts of meter were disregarded) and supposedly vulgar content, but Ralph Waldo Emerson greeted the work as "the beginning of a great career." Whitman quickly followed the first edition sketch with a 2nd edition the following year, reworking some of his original poems and including 21 new ones, such as the "Sun-down Poem (Crossing Brooklyn Ferry)"; and in 1860, he found a publisher for a 3rd edition, including the "Calamus" poems, detailing a homosexual love affair gone bad (leading some to speculate that Whitman was a homosexual; when pressed, however, Whitman denied he was a homosexual and claimed to have fathered 6 illegitimate children) and "A Word Out of the Sea" (later known as "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking").

With the onset of the Civil War, Whitman resolved to leave his bohemian life behind and concentrate on serious matters. His spiritual sobriety deepened when his brother George was wounded at Fredericksburg. Traveling there to visit him at a battleground hospital in 1862, he was horrified by the sight of heaps of amputated arms and legs, but instead of turning away he went to Washington to volunteer as a nurse at the Army hospital while working as a federal government clerk.

In 1865, Whitman published two volumes of poems about the Civil War, Drum Taps and its sequel, which contained an elegy to the recently assassinated Abraham Lincoln, "When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom'd." (Lincoln, perhaps predictably, was an admirer of the early editions of Leaves of Grass.) After being chased out of the government for writing indecent material, Whitman found a number of critical supporters, both in the U.S. and in England. He settled down in Camden, New Jersey, lecturing occasionally, producing new editions of Leaves of Grass (a 9th authorized edition appeared in 1892) and enjoying his status as a legendary man of letters. He died on March 26, 1892 in Camden, New Jersey.

Labels: Literature

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home