Novus Mundus

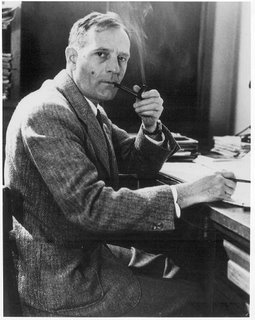

Amerigo Vespucci -- explorer, geographer and merchant, the first to call the Americas "the New World" and the incidental inspiration for the naming of those continents -- was born on this day in 1451 in Florence.

Vespucci has long taken the rap for being a fraud who had never sailed anywhere special and who had misappropriated the naming rights to the continent discovered by his rough acquaintance, Christopher Columbus. As is usually the case, the real story is a little more interesting than that. Born of a noble family, the classically-educated Vespucci, who grew up with a love of literature, astronomy and geography, ingratiated himself with the powerful Medici family (who were easily impressed by intellectual types) and got himself hired as a sort of purchasing agent and sales rep for their ship-outfitting business in Spain.

A welcome visitor at the court of Isabella and Ferdinand, he watched Columbus' first 2 voyages with interest, and furrowed his brow each time Columbus returned to declare that he had discovered a Western sea route to India. He decided to get to know Columbus a little better, and through his salesmanship became Columbus' key supplier for his third voyage across the ocean in 1497.

Hearing nothing with his skeptical ears that suggested that the coarse Genoan had actually found India, Vespucci decided, as a scientist, that he needed to go and see for himself, so in 1499 he outfitted his own voyage West and set sail under the Spanish flag. Arriving at the northern coast of what would eventually be called South America, he explored the Amazon and promptly fell into the same trap that had snagged Columbus, in that Vespucci initially insisted on calling the Amazon "the Ganges." However, with his superior skills as an astronomer, he did develop a method for determining longitude which became the standard for 300 years, and was able to estimate the circumference of the Earth to within 50 miles.

On his second trip in 1501 (this time on behalf of Portugal rather than Spain), Vespucci made his breakthrough: tracing the coast of the continent down to within 400 miles of Tierra del Fuego, he charted his progress and came to the realization that the land was not India at all, but an entirely "New World" previously unheard of in the courts of Western Europe. With that also came the revolutionary realization that there were 2 great oceans rather than one separating Europe from Asia to the West -- one greater than the one that Columbus had crossed and which Columbus had never even reached because of the big continents that stood between them. Vespucci reported his findings to the Medicis in 2 brief but erudite letters, the first called Novus Mundus (or "New World"), which when published shortly thereafter caused a sensation. He died on February 22, 1512 in Seville, Spain.

Meanwhile, Vespucci himself never presumed to name the new continent for himself; the name came from a map published by a German preacher named Martin Waldseemuller in 1507, who mistakenly declared Vespucci the discoverer of the continent, and upon that claim quite naturally decided it should be named for him. Columbus, for his part, never gave up believing that he had found the route to India, and though he continues to get all the credit for having discovered the New World, it was Vespucci who figured out that it was "New."

Labels: Astronomy, Exploration, Italy, Navigation