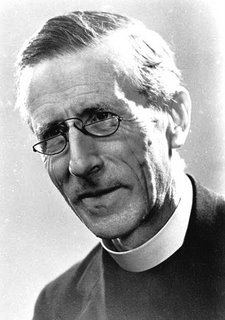

Teilhard de Chardin

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born on this day in 1881 in Sarcenat, France.

The son of a farmer and amateur naturalist, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin entered the Jesuit College at Mongré at the age of 10, and joined the Jesuit novitiate when he was 18. After the Waldeck-Rousseau laws forced the Jesuits to flee France, Teilhard began a period of exile on the Isle of Jersey (going on geologic field trips), in Cairo and elsewhere in Egypt (teaching physics and chemistry at the Jesuit College and continuing to study geology), and finally in Hastings, Sussex, where he was ordained as a priest in 1911 at the age of 30.

Rather than pursuing a career in the Church, however, Teilhard went to work in the paleontology laboratory at the Museum of Natural History in Paris until the beginning of World War I, when he joined the French 8th Regiment of Moroccan rifleman (later the 4th Regiment of Zouaves and Light Infantry) as a stretcher-bearer. By the War's end, he had completed his novitiate during a leave (taking his solemn vow to enter the Jesuit brotherhood) and received the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille Militaire for his heroism. Teilhard later wrote that the "war was a meeting . . . with the Absolute," inspiring him to write an essay, "The Cosmic Life" -- a first, furtive explication of his developing ideas of science, philosophy and mysticism -- although, during his lifetime, most of his published works concerned mammalian paleontology and Asian geology.

As early as 1924, Teilhard's earnest attempts at drawing modern science together with Roman Catholic dogma (specifically, an attempt to reconcile the concept of "original sin" with evolution) were greeted coldly by ecclesiastical authorities, and he was basically forbidden to publish his spiritual writings. Teilhard, though patient and respectful, lived a double life -- outwardly devoting himself to geological expeditions throughout Asia and gaining worldwide renown for his scientific contributions, but privately continuing to write down his meditations.

Beginning in the mid-1920s, Teilhard went to China, where he worked on the Chinese national geological survey and assisted archaeologist Pei Wenzhong at the unearthing of the first discovered skull of the hominid "Peking Man" (1929). During 1930-1, he explored the Gobi with Roy Chapman Andrews' American Center-Asia Expedition and participated in Georges-Marie Haardt's "Yellow Cruise" along the old Silk Road in a fleet of Citroën P2s, joining the group in Beijing and traveling to Urumqi, the capital of Sinkiang.

In 1937, he wrote The Divine Milieu while sailing on the Empress of Japan to the U.S., where he was given the Mendel Medal at Villanova. On that occasion, he gave a speech about evolution, prompting the New York Times to portray him as the Jesuit who claimed that man was a mere instrument of evolution; Catholic University of Boston, which had been scheduled to bestow an honorary doctorate upon him, quickly called him to cancel the honor. Adding insult to injury, as it were, in 1950 Pius XII issued the encyclical Humani generis, which came to be seen as a harsh retort to Teilhard's requests for permission to publish his theory of evolution.

Just what was the substance of Teilhard's questionable writings, which eventually came to be published after his death and were influential enough to merit an advisory by the Church against uncritical acceptance of his ideas? In The Divine Milieu and The Human Phenomenon, Teilhard advances the notion that evolution is a divine process resembling "a way of the Cross" for all life on Earth. Classical theology, in Teilhard's view, can be harmonized with modern scientific thought, particularly about evolution, if one accepts the idea that basic material processes such as gravity, inertia and electromagnetism have contributed toward the creation of increasingly complex entities, from atoms to molecules to cells, and ultimately to the aggregation of biological systems we know as human beings -- entities that are possessed of self-awareness and that are capable of moral responsibility. At the same time that evolutionary processes have contributed to the diversity of species that currently exist on Earth, Teilhard's fundamental starting point is that "each one of us is perforce linked by all the material organic and psychic strands of his being to all that surrounds him."

For Teilhard, evolution is the process of the physical and moral convergence of these strands (affecting both the biosphere and the "noosphere," the sum total of the cultural achievements of humanity) which is aimed at a complete and final unity with God called the "Omega point" -- a kind of superconsciousness of all life on Earth, similar in some ways to Bruno's "world-soul" or Lovelock's concept of Gaia. In his belief in evolution as a process of transcendence, Teilhard provides his readers with a glimpse of a kind of cosmic redemption, ultimately summarizing his equation of science and theology with the optimistic assertion that "Christ is realized in evolution."

He died on April 10, 1955 in New York City.

Labels: Christian History, Evolution, Geology

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home