The Rights, and Wrongs, of Women

"Contending for the rights of women, my main argument is built on this simple principle, that if she be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge, for truth must be common to all, or it will be inefficacious with respect to its influence on general practice." -- Mary Wollstonecraft.

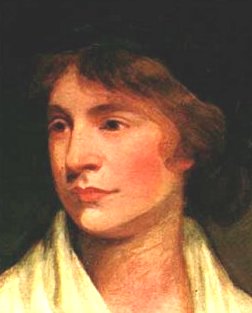

"Contending for the rights of women, my main argument is built on this simple principle, that if she be not prepared by education to become the companion of man, she will stop the progress of knowledge, for truth must be common to all, or it will be inefficacious with respect to its influence on general practice." -- Mary Wollstonecraft.The eldest daughter of an unsuccessful farmer who didn't believe in the education of women, Mary Wollstonecraft (born on this day in 1759 in Hoxton, London) learned to love literature through the kindly intervention of a nearby childless couple.

At 19, she defied her parents to become the paid companion of a wealthy widow, but she proved to be too independent and critical-minded to settle easily into society. In 1781, she left her position to nurse her dying mother, then rushed to her sister Eliza's side upon the birth of Eliza's daughter in 1783, finding Eliza suffering from a breakdown due to her unhappy marriage. Wollstonecraft assisted Eliza in escaping from her husband's household, eventually taking her to Newington Green, London, to open a school for young women. Shortly after establishing it, Wollstonecraft left for Portugal to be with her best friend, Fanny Blood Skey, who was pregnant, and arrived just in time to see her friend die.

When she returned to Newington Green, the school had to be closed, but her friends at Newington Green recognized her talent, and urged to her to turn to writing. In 1797, while serving as a governess in Ireland, she wrote a pamphlet, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, and followed that by a novel, Mary, a Fiction (1788), a satire on manners drawn from her experiences in Ireland. She returned from Ireland to London, joining a circle of independent thinkers which included Thomas Paine, William Godwin, Henry Fuseli and William Blake, and began contributing short pieces to The Analytical Review. In 1789, she edited an anthology for women's education, The Female Reader, which included excerpts from Shakespeare, the Bible and William Cowper.

Her next project grew out of contemporary politics. A friend of hers, Dr. Richard Price, delivered a sermon in November 1789 praising the first steps of the French Revolution as advances in human liberty; in response, Edmund Burke wrote Reflections on the Revolutions in France (1790), which asserted that liberation was the product of adherence to tradition, not of bloody revolution. Wollstonecraft responded to Burke with her Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), which was a source of controversy not only for its radical views, but that it represented the attempt of a woman to enter the male world of political debate.

Wollstonecraft was exhilarated by her notoriety, and with her mind turning upon a significant point which was left unsaid in her Rights of Men pamphlet, she wrote and published a follow-up, A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1791). Rights of Women became a landmark in the history of women's writing: in it, she analyzed the ways in which women have been held subservient to men throughout the centuries and made the startling point that women were not naturally submissive, but that femininity and submissiveness was taught to young women and rewarded.

Where she was a curiosity before the publication of Rights of Women, afterwards she was a genuine literary celebrity. Her very celebrity, however, undermined her effectiveness as a commentator; conservatives who wished to repudiate her views on women's education pointed with hushed whispers to her personal life. Before moving to Paris in 1792, she had attempted to engage Fuseli, who was married, in an "open marriage" arrangement with his wife (she was rebuffed and humiliated by the attempt); then entered a relationship with Gilbert Imlay, an American adventurer in Paris, and became pregnant. Her daughter Fanny was born in 1794, and shortly thereafter Imlay grew tired of Wollstonecraft and fled, leaving Wollstonecraft almost hysterical.

Despite the personal turmoil, she wrote An Historical and Moral View of the Origin and Progress of the French Revolution (1794). She followed Imlay back to London, hoping to set up house with him, but he had moved onto other things, and Wollstonecraft fell to grief and attempted suicide. Feeling guilty, Imlay invited her to accompany him to Sweden on business; it was an unsatisfactory trip, and Wollstonecraft returned to London in 1795 and attempted to drown herself in the Thames River.

Shortly thereafter, she renewed her acquaintance with William Godwin, an admirer of her work, and they became lovers. Though they both reviled marriage as an oppressive institution, they surprised their friends by getting married in 1797, a few months after Wollstonecraft discovered she was pregnant by Godwin. During her pregnancy, she worked on another novel, The Wrongs of Women (unfinished but published posthumously by Godwin, 1798). Her daughter, Mary Godwin (who would later know fame as the novelist Mary Shelley) was born on August 30, 1797; but Wollstonecraft died a few days later from complications of childbirth.

Labels: Literature, Trailblazing Women

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home