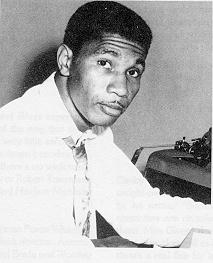

Medgar Evers

"It may sound funny, but I love the South. I don't choose to live anywhere else. There's land here, where a man can raise cattle, and I'm going to do it some day. There are lakes where a man can sink a hook and fight the bass. There is room here for my children to play and grow, and become good citizens -- if the white man will let them." -- Medgar Evers.

Civil rights leader Medgar Evers was born on this day in 1925 in Decatur, Mississippi.

A veteran of Normandy and the French campaign, Medgar Evers returned to Mississippi after World War II to find little had changed since he had left. When he was 14, he witnessed the lynching of one of his father's friends for supposedly insulting a white woman, and even if he did not necessarily personally witness the same kind of shocking violence perpetrated against African-Americans by whites, it still existed, and bigotry still defined the community's attitude toward African-Americans.

After graduating from Alcorn State with a degree in business administration in 1952, Evers joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and tried unsuccessfully to register at the segregated University of Mississippi Law School after the Supreme Court ruled that segregation was unconstitutional in Brown vs. Board of Education (1954; argued by future Supreme Court justice Thurgood Marshall). When he asked if the NAACP would file suit on his behalf, the organization asked him to be the NAACP's field secretary (the only paid position within Mississippi), which led to his investigation of racial violence, organization of voter registration drives and other work for desegregation. Settling in Jackson, Evers protested, again without success, to the Federal Communications Commission to be allowed to have equal time on a local television to answer anti-African-American statements made by white politicians in 1957.

His protests and investigations, though conducted with Evers' natural air of quiet dignity and reasonableness, began to attract the attention of white authorities, who began a systematic program of persecution against him. In 1958, for example, he was arrested for sitting in a "white" bus seat in Meridian; in 1960 he was sentenced to 30 days in jail and fined $100 for criticizing the conviction of another African-American; and in 1962, Evers was beaten by a courtroom policeman when he applauded a defendant who was being prosecuted for his role in a sit-down demonstration. In late 1962 and 1963, while Martin Luther King was staring down Bull Connor and his police dogs in Birmingham, Alabama, Evers stepped up the pace of the civil rights movement in Jackson, publicly advocating the hiring of African-American policeman and orchestrating the first economic boycott of downtown merchants who practiced apartheid, in the process attempting to give African-Americans a reason for shrugging off the sense of inferiority which often curbed their call to action.

As Evers' profile and methods rose in pitch, threats on his life also increased. By June 1963, the Evers family had become accustomed to regular duck-and-cover drills whenever they heard a strange noise outside their home; and on the evening of June 12, 1963, the family's worst fears were fulfilled as Evers was ambushed, shot in the back as he got out of his car. Evers was rushed to a hospital, which initially would not admit him because he was black, but soon afterward tried unsuccessfully to save him once they found out who he was.

5,000 mourners marched through the streets of Jackson at his viewing, and his murder brought the attention of the world to the continuation of hate in the American South -- only a day or two after George Wallace tried to stand in the doorway of the University of Alabama to block the entry of African-American students, and a few hours after President Kennedy delivered a speech describing America's "moral crisis" over African-American civil rights.

By some accounts, Evers' assassination helped to turn the tide toward the passage of civil rights legislation through Congress; yet bigotry still defined Evers' posthumous relationship with Mississippi, as his accused murderer, Byron de la Beckwith, was set free after two hung-jury mistrials despite overwhelming evidence against him, some of it compiled by the FBI. In 1989, de la Beckwith was arrested again by Mississippi authorities based on new evidence and in a somewhat more enlightened racial climate, and on February 5, 1994, he was finally convicted of Evers' murder.

Evers' brother Charles succeeded him as NAACP field secretary in Mississippi, and in 1995 his widow, Myrlie Evers Williams, was elected chair of the national board of directors of the NAACP. Evers was buried, with full military honors, at Arlington National Cemetery, providing the nation with an immediate reminder of the equal part played by African-Americans in time of war. A statue now honors his memory in Jackson.

Labels: Civil Rights

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home