The American Afghan Prince

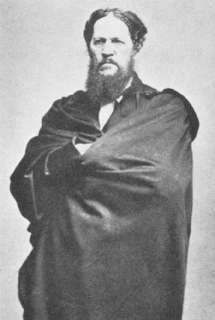

The Afghan "Prince of Ghor and Lord of the Hazaras" was born on this date in 1799 in, of all places, Newlin Township, Pennsylvania.

While on a merchant mission to India in 1822, a "Dear John" letter from his fiancée stirred Josiah Harlan, a Quaker and Freemason, to stay in Asia and find his fortune. Without any meaningful training for the profession, Harlan's fast talk landed him positions as a surgeon, first for the British East India Tea Company, and later for the Bengal artillery under British colonel George Pollock during the First Burmese War (1824-6).

Finding himself out of work after the war and inspired by tales of Alexander the Great's conquest of Central Asia, Harlan insisted on traveling to a part of the East that few Westerners -- let alone any Americans -- had ever seen. In a small border town in 1827, Harlan met the deposed former king of Afghanistan, Shoja al-Molk Shah, and promised him that he would go to Kabul, raise his supporters, and overthrow the new regent, Dost Mohammad Khan. Hedging his bets, he also offered his services as a military reconnaissance scout to the leader of the Sikhs in the Punjab, Ranjit Singh.

Arriving in Kabul in 1829, after mastering Persian and successfully navigating the complex relationships among Afghan tribes while masquerading as a Muslim holy man, Harlan quickly determined that Dost was a worthy and formidable ruler, and he abandoned his effort, returning to the Punjab with copious intelligence about Dost's regime to become Singh's governor of the provinces of Durpur and Jesota. In 1835, Dost's army launched an attack on Singh, who in retaliation sent Harlan along to infiltrate Dost's camp and bribe his men with gold, resulting in Dost's retreat. Harlan nevertheless decided to switch sides and join Dost in 1836, organizing and training Dost's army and preparing them for their defeat of Singh at the battle of Jamrud in January 1837. For his service to Dost, Harlan was named "prince of Ghor, lord of the Hazaras," a title he enjoyed for only a short time before the British entered Afghanistan in their bid to conquer it in 1839, forcing him to leave.

Appalled by British tactics and what he perceived to be their fatal insensitivity to local customs ("I have seen this country, sacred to the harmony of hallowed solitude, desecrated by the rude intrusion of senseless stranger boors, vile in habits, infamous in vulgar tastes," he wrote), Harlan returned to the U.S. and wrote a scathing critique of the British in A Memoir of India and Afghanistan (1842). In view of the fact that it was published in the same year that the British were driven out of Afghanistan by Dost, Harlan's point of view was rather harshly denounced by the smarting British.

Harlan married and settled down on an estate in Chester County, Pennsylvania, briefly involving himself in an effort to import camels to the U.S. in 1856. He fought in the Union Army during the Civil War as commander of "Harlan's Light Cavalry," participating in the Peninsular campaign before retiring, due to ill health, to San Francisco in 1862, where he practiced his ill-informed version of medicine, fading into obscurity. He died October 1871 in San Francisco, California.

Tales of the unprincipled, delusional, yet seemingly effective American mercenary -- some derisive, some admiring -- continued to drift among British adventurers, ultimately forming the basis of Rudyard Kipling's fictional story "The Man Who Would be King" (1888; filmed by John Huston with Sean Connery in the anglicized role based on Harlan), and providing an interesting background and counterpoint to 20th/21st century American foreign policy in Afghanistan, from its support of the Mujahideen against the Soviets in the 1980s to the hunt for Osama bin Laden after 2001.

Labels: Afghanistan

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home