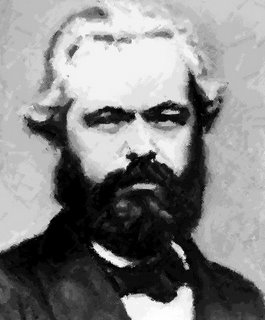

Marx

Much maligned by the post-Soviet world as a symbol of what the Soviets stood for, if Karl Marx were alive today he would no doubt be flattered by the attention, energized by his critics, but probably mystified by his identification with the Soviets, as he was when he learned before his death that a party in France had called itself a "Marxist" party; his response: "I, at least, am not a Marxist."

Born on this day in 1818 in Trier, Germany, Karl Marx was descended from a long line of rabbis on his mother's side. Marx's father Heinrich had changed his surname from "Levi" to "Marx" shortly before Karl's birth and converted to Lutheranism, hoping to take his place as a lawyer and community leader in Trier. While taking pro-monarchial stands in public, Heinrich privately raised his son Karl on the revolutionary, democratic writings of Locke and Voltaire. Young Karl devoured it all, in addition to all of the literature and poetry he could get his hands on, becoming, in his teens, a precocious scholar of Homer and Shakespeare with the encouragement of the Marxes' aristocratic neighbor, Baron Ludwig von Westphalen.

While words became his passion, Marx also developed an intense affection for Baron von Westphalen's daughter, a pretty and popular girl 5 years his senior named Jenny; and by the time Marx left Trier for the University of Bonn in 1835, they were secretly contemplating marriage. Heinrich Marx's plan was for his son to follow him into the law, but at first Marx seemed intent only to study beer, as co-president of Bonn's Trier Tavern Club; brawling (one scuffle with a Bonn gang resulted in a sword slash over Marx's eye); and the composition of love poems to Jenny, who consented to be his fiancée in 1836. His father, irked by the engagement and angry about his son's "rampaging" in Bonn, called for Karl's transfer to the University of Berlin. There, Marx did manage to come to the realization that he had no future as a poet, but yet the study of the law still took a back seat to his newly-found passion, the controversial philosophy of the late Berliner, G.W.F. Hegel. Embracing a new regimen that would last for most of the rest of his life, Marx eschewed company and poured over academic texts all night by candlelight, smoking cheap cigars and sipping cheap ale. With the idea of becoming a professor, Marx completed a doctoral thesis likening the debates over Hegel to the disputes between followers of Epicurus and Democritus.

Marx's literary antics, however -- anonymously penning a spoof against the Prussian monarchy, for one -- undermined both the pursuit of his doctorate (he finally received one from Jena, on a correspondence basis, in 1841) and his dreams of landing a job as a professor, so in 1842 he moved to Cologne and took over the helm of a small liberal newspaper, Rheinische Zeitung. Within 5 months, Marx's paper was shut down by the government for his complaints about local housing conditions and his criticism of the Czar Nicholas I.

He married Jenny in 1843, and moved to Paris, where he became aligned with the communists (then supporters of the utopian socialism of Etienne Cabet) and assumed the editorship of a journal-in-exile that opposed the Prussian government, which failed shortly thereafter when distribution in Germany became impossible. In Paris, Brussels and Cologne, he earned a reputation as a combative, intellectually acute "wild boar" (to paraphrase Jenny Marx), and was kicked from city to city by impatient officials (at least once on the direct intervention of Frederick William IV).

Among his Paris admirers was Friedrich Engels, the son of a rich industrialist, who would become Marx's lifelong colleague, apologist and benefactor. In an effort to set forth the principles of a burgeoning anti-bourgeois radical movement, Marx and Engels wrote the 21-page Communist Manifesto (1848), a utopian polemic, published in the midst of the riots leading to the abdication of Louis Phillippe in France and similar unrest in Berlin, Prague and Vienna, which called for workers to throw off the bourgeoisie and establish a property-less, classless society. Ultimately booted from Cologne and banished to a town in Brittany after using part of his mother's inheritance to buy "blood-red ribbons" for the Paris Communists, Marx finally moved his family to London's Soho district in 1849.

Living in dire poverty, he eked out a living as a journalist, occasionally speaking out as a leader of the First International (a group of radicals who had played a small role in the Paris Commune of 1871), while tending to his true calling -- occupying a dark corner of the British Museum, reading Adam Smith and David Ricardo and countless econometric studies and tracts, in preparation for the writing of his life's work, which would come to be known as Das Kapital (1867-94). In effect, it would be a top-to-bottom study of capitalism with an eye toward exposing its inherent structural flaws.

Picking up where the Communist Manifesto left off, much of what became influential in Marx's thought among the Russians, the Chinese and their constituents can be found within its dense pages. His "historical materialism" was simply a theory about history in which Marx held that the history of society is the history of class struggles -- contemporarily, in 19th century Europe, the struggles between the bourgeoisie (big capitalists) and the property-less proletariat. Impinging on this class conflict and the social relations inherent in the activity of producing goods were "production forces" -- not just human labor, but technological advancements and other popular currents. For the production forces that exist in a given economy, according to Marx, there is a set of social relations which will, as a result of conflicts or otherwise, naturally coalesce around them, ultimately inspiring an enabling superstructure of laws, political institutions, religion, art and philosophy. Thus, for Marx there is a kind of self-feeding inevitability, or "historical determinism," to human processes that arises out of conflict.

In Das Kapital, Marx further defends and elaborates this thesis, introducing the "labour theory of value" and the "theory of surplus value" to illustrate how the engines of capitalism deprive the worker of the true value of his or her labor, showing the chinks in the armor of 19th century capitalism that would result in the next big change. Marx's most passionate writing describes the rise of capitalism, its inherent miseries, and its trend toward the centralization of production and socialization of labor which ultimately will cause capitalism as we know it to "burst asunder."

Although it was clear to Marx that the activism of the proletariat would be an essential ingredient in the demise of capitalism, Marx also suggested that for change to take hold, there could be no skipping of steps: the next phase, the hoped-for classless society, could only occur as capitalism reached its most mature, hopelessly self-immolating zenith. Impatient disciples such as Lenin and Mao summarily ignored this aspect of Marx, of course, taking barely post-feudal agrarian societies and violently yanking them to a version of a communistic society Marx never actually envisioned. Indeed, Marx never actually described the post-capitalistic society in any detail, arguing that it wasn't his job to "draw up recipes for the cookshops of the future." When asked who would shine shoes in a post-capitalist society, Marx replied (with tongue firmly in cheek), "You should."

Two of Marx's indelicate phrases -- "the dictatorship of the proletariat" and "religion is the opiate of the masses" -- were writerly impertinences: in the former, he was describing what he saw as an inevitable temporary state of affairs as the institutions of capitalism violently came tumbling down, to wither away completely upon the emergence of a classless society; in the latter, he merely referred to the comfort workers take in worship when all else is drudgery. Although not religious himself, Marx did charitably observe, "We can forgive Christianity much, because it taught us the worship of the child."

Marx's influence on the West, apart from the radical activities of party regulars, was to form the basis of a critique of the social superstructure, enabling the Western Left to trace the ideological roots of Western law, politics, literature and other institutions back to the economic structures on which they are based. To those who would argue, say, that the U.S. Constitution and the Bill of Rights are autonomous embodiments of "liberty," Marx might say that this was a "false consciousness" and that the point of view fails to understand or acknowledge the ways in which those laws are designed to promote the economic status quo in the service of the ruling bourgeoisie.

Also essential to the Marxist critical arsenal was Marx's concept of "alienation," first articulated in his unpublished "Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts" (1844) -- the notion that human beings are not "themselves" in a capitalist society in which they lose the full value of their labor, that they are not permitted to fulfill their full human potential. In Marx's view of alienation, those who continue to see Marx as a prescient thinker on economic issues -- one who would have been unsurprised by globalization, accounting scandals or the rise of Wal-Mart -- find a hopeful vision of a post-capitalist society in which humanity takes precedence over property.

Marx himself was, however, an abject slave and victim of capitalism -- always behind in his bills, relying on Engels' handouts, losing some of his children to illnesses of poverty. He died poor and relatively obscure on March 14, 1883 in London -- but at his funeral in Highgate Cemetery, Engels, at least, knew that his friend's name would not be forgotten.

Categories: Philosophy, Economics, Marxism

Labels: Economics, Marxism, Philosophy

3 Comments:

OK, where's Manchester, UK?

Engels wrote extensively on the conditions the working class lived in in Manchester and (I believe) Marx and Engels actually started the Communist manifesto in the Chethem's School library in the said city.

It was Manchester more than any other city which gave Marx the suggestions of how intolerable capitalism was for the working people.

(And, yep, got a connection - come from the place and my family lived in the area Engels described).

Mr. Farrar, you are one well-connected fellow.

It's also Kierkegaard's birthday, May 5, 1813. The two greatest critics of Hegel born on the same day... What a coincidence.

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home