Ohio Politicians

Ohio has produced more than its fair share of presidents of the United States, as no doubt every Ohio schoolteacher is obliged to point out to his or her charges. It is also very true that the state has produced more than its fair share of political mediocrities.

The shame of it all is that there is such an excellent correlation between the former and the latter fellowships. Setting aside the ambivalent reputation of William McKinley, names like Harrison, Grant, Hayes, Garfield, Taft and Harding hardly spring to mind as being among the finest of our commanders-in-chief.

William H. Taft was probably a better president than he was a politician, and certainly a better judicial administrator as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court than either president or politician. His surname has come to dominate Ohio politics for almost a century; the family’s reputation for principled activism and ethical propriety seemed ably advanced by the president’s son, Bob “Mr. Integrity” Taft – held to be one of the Senate’s most effective leaders ever – and by the persistently un-chic Bob Taft, Jr. (U.S. congressman and senator during the 1960s and 70s).

The latest scion of the Taft family, governor Robert A. Taft II (excuse the confusing family nomenclature), appears to fall more squarely within the grand tradition of Ohio dunderheadedness, however. Convicted of four misdemeanor ethics violations and still embroiled in a scandal over the disappearance of more than $10 million from the coffers of the Ohio workers comp fund entrusted to his some-time golf partner, rare coin dealer Thomas Noe (isn’t it comforting to know that state money can be invested in rare coins, autographs and other memorabilia?), Taft’s approval ratings now seem to be lingering somewhere around 15%. Frank Newport, the editor of the Gallup Poll, registers his astonishment at the number, observing that "Almost any figure who's elected in a partisan election usually has at least some support from his party . . . Usually there's a party base. It's hard mathematically to get that low." Quite an achievement.

Today is the anniversary of the births of two other Ohio politicians – both fairly obscure.

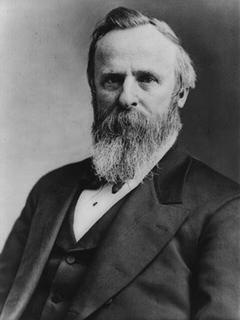

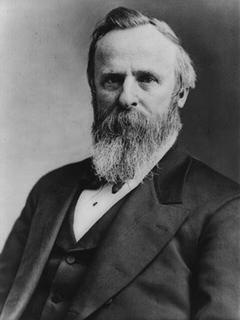

The aforementioned, perhaps unfairly maligned Rutherford B. Hayes was born on this day in 1822 in Delaware, Ohio. His father died from fever 11 weeks before the birth of his son, leaving Hayes' mother to raise two children and support them by renting out part of her farm to sharecroppers. Despite the hardship, Hayes attended Harvard Law School and became a respected Cincinnati lawyer before entering the Union Army in the Civil War as a major. He was still in uniform when he was elected to Congress as a Republican, his prospects boosted by the publication of a letter in which he stated that it would be a disgrace to return home to campaign for the seat while he was still fit for military service; he left the Army as a major general in June 1865.

Following two terms in Congress, Hayes was elected governor of Ohio in 1868, where he encouraged merit appointments, education and prison reform and reduced the state's budget deficit. He served two terms, the traditional limit, and then beat his successor, William "Earthquake" Allen, to regain the governorship in 1876.

At the Republican Convention that year, Hayes became the beneficiary of a "Stop James Blaine" movement and was nominated for president to face New York Democrat Samuel Tilden (by reputation, a kind of Eliot Spitzer of his day) in the 1876 election. During the campaign, Hayes found himself having to distance himself from the corrupt administration of fellow Republican and fellow Ohioan Ulysses S. Grant, but nevertheless drew the support of reformers like Carl Schurz on the basis of his record in Ohio.

Hayes lost the popular vote to Tilden, 51% to 49%, and the day after the election Hayes conceded his loss to Tilden, who would have been the first Democrat to be elected president since before the Civil War. Meanwhile, election returns in three key states (South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana) were in confusion, leaving Tilden's apparent electoral majority uncertain. To resolve the issue, Congress appointed a 15-man bi-partisan electoral commission of congressmen, senators and Supreme Court justices (8 Republicans, 7 Democrats). In February 1877 the commission voted along party lines to award the electoral votes of all the disputed states to Hayes, resulting in Hayes' election as president. Some Southerners threatened rebellion over what they perceived to be a stolen election (calling him “Rutherfraud”), but Tilden accepted defeat, and Hayes, in his most significant act while president, agreed to end the military rule which had been imposed on the South after the Civil War.

At the end of one term as president, Hayes retired, devoting the rest of his life to supporting African-American education charities (he personally awarded a scholarship to the future African-American civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois). Late in life, he was particularly concerned about the disparity in wealth between industrialists and workers, and favored state controls over the distribution of wealth, although he never fully embraced Socialism.

Oddly enough, while he is nearly forgotten in the U.S., today he is revered as a near-saint in Paraguay for his role in settling Paraguay's border dispute with Argentina over an uninhabitable outback known as the “Chaco.” Paraguayans celebrate an annual holiday in his honor, some calling him the “greatest man in Paraguayan history.”

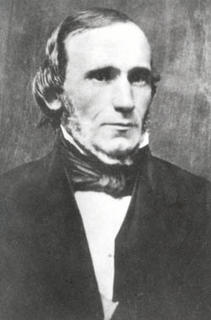

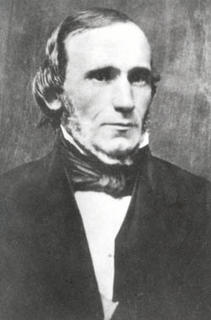

Meanwhile, John Scott Harrison, who if alive would have celebrated his 201st birthday today, came nowhere near becoming president himself. He was, however, the only man cursed to be the son of one U.S. president (William Henry Harrison) and the father of another (Benjamin Harrison). Both his father and his son would have to be described as near nonentities on the stage of American history. John Scott Harrison briefly studied medicine (like his father), and served two terms as a Whig congressman from Ohio, but was defeated for reelection in 1856 as the Whig Party went into a state of mummification. He died in 1878 at his “Point Farm” in North Bend, Ohio, before his son had made a successful entry into politics.

Meanwhile, John Scott Harrison, who if alive would have celebrated his 201st birthday today, came nowhere near becoming president himself. He was, however, the only man cursed to be the son of one U.S. president (William Henry Harrison) and the father of another (Benjamin Harrison). Both his father and his son would have to be described as near nonentities on the stage of American history. John Scott Harrison briefly studied medicine (like his father), and served two terms as a Whig congressman from Ohio, but was defeated for reelection in 1856 as the Whig Party went into a state of mummification. He died in 1878 at his “Point Farm” in North Bend, Ohio, before his son had made a successful entry into politics.

Harrison is perhaps best remembered for the peculiar circumstances of his burial. When Harrison was buried at his father's tomb near the family estate, it was noticed that a nearby grave had been robbed. Extra precautions were taken to make sure that Harrison's body would not be subject to a similarly rude disinterment, and his body was placed in a metal coffin encased in cemented marble slabs. During a search for the missing body from the nearby grave, authorities were startled to find John Scott Harrison's body, swinging upside down from a rope in a shaft in the Ohio Medical College in nearby Cincinnati -- stolen by Dr. Henri Le Caron just a few hours after his burial despite the extra security.

Ironically, Harrison's greatest personal impact on American public policy was that following the shameful grave-robbing incident, many state legislatures began to pass laws making it easier for medical schools to obtain cadavers for experimentation by legal means. John Scott Harrison may have been a political nobody, but given the track records of Ohio political notables over the years, perhaps Harrison’s legacy could be held as a standard for the aspirations of future Ohio politicians.

See also:

Chuck Todd, National Journal Hotline, "The Ghost of Teddy" (10/4/2005) on John McCain's "odd call" for Governor Taft's resignation

The shame of it all is that there is such an excellent correlation between the former and the latter fellowships. Setting aside the ambivalent reputation of William McKinley, names like Harrison, Grant, Hayes, Garfield, Taft and Harding hardly spring to mind as being among the finest of our commanders-in-chief.

William H. Taft was probably a better president than he was a politician, and certainly a better judicial administrator as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court than either president or politician. His surname has come to dominate Ohio politics for almost a century; the family’s reputation for principled activism and ethical propriety seemed ably advanced by the president’s son, Bob “Mr. Integrity” Taft – held to be one of the Senate’s most effective leaders ever – and by the persistently un-chic Bob Taft, Jr. (U.S. congressman and senator during the 1960s and 70s).

The latest scion of the Taft family, governor Robert A. Taft II (excuse the confusing family nomenclature), appears to fall more squarely within the grand tradition of Ohio dunderheadedness, however. Convicted of four misdemeanor ethics violations and still embroiled in a scandal over the disappearance of more than $10 million from the coffers of the Ohio workers comp fund entrusted to his some-time golf partner, rare coin dealer Thomas Noe (isn’t it comforting to know that state money can be invested in rare coins, autographs and other memorabilia?), Taft’s approval ratings now seem to be lingering somewhere around 15%. Frank Newport, the editor of the Gallup Poll, registers his astonishment at the number, observing that "Almost any figure who's elected in a partisan election usually has at least some support from his party . . . Usually there's a party base. It's hard mathematically to get that low." Quite an achievement.

Today is the anniversary of the births of two other Ohio politicians – both fairly obscure.

The aforementioned, perhaps unfairly maligned Rutherford B. Hayes was born on this day in 1822 in Delaware, Ohio. His father died from fever 11 weeks before the birth of his son, leaving Hayes' mother to raise two children and support them by renting out part of her farm to sharecroppers. Despite the hardship, Hayes attended Harvard Law School and became a respected Cincinnati lawyer before entering the Union Army in the Civil War as a major. He was still in uniform when he was elected to Congress as a Republican, his prospects boosted by the publication of a letter in which he stated that it would be a disgrace to return home to campaign for the seat while he was still fit for military service; he left the Army as a major general in June 1865.

Following two terms in Congress, Hayes was elected governor of Ohio in 1868, where he encouraged merit appointments, education and prison reform and reduced the state's budget deficit. He served two terms, the traditional limit, and then beat his successor, William "Earthquake" Allen, to regain the governorship in 1876.

At the Republican Convention that year, Hayes became the beneficiary of a "Stop James Blaine" movement and was nominated for president to face New York Democrat Samuel Tilden (by reputation, a kind of Eliot Spitzer of his day) in the 1876 election. During the campaign, Hayes found himself having to distance himself from the corrupt administration of fellow Republican and fellow Ohioan Ulysses S. Grant, but nevertheless drew the support of reformers like Carl Schurz on the basis of his record in Ohio.

Hayes lost the popular vote to Tilden, 51% to 49%, and the day after the election Hayes conceded his loss to Tilden, who would have been the first Democrat to be elected president since before the Civil War. Meanwhile, election returns in three key states (South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana) were in confusion, leaving Tilden's apparent electoral majority uncertain. To resolve the issue, Congress appointed a 15-man bi-partisan electoral commission of congressmen, senators and Supreme Court justices (8 Republicans, 7 Democrats). In February 1877 the commission voted along party lines to award the electoral votes of all the disputed states to Hayes, resulting in Hayes' election as president. Some Southerners threatened rebellion over what they perceived to be a stolen election (calling him “Rutherfraud”), but Tilden accepted defeat, and Hayes, in his most significant act while president, agreed to end the military rule which had been imposed on the South after the Civil War.

At the end of one term as president, Hayes retired, devoting the rest of his life to supporting African-American education charities (he personally awarded a scholarship to the future African-American civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois). Late in life, he was particularly concerned about the disparity in wealth between industrialists and workers, and favored state controls over the distribution of wealth, although he never fully embraced Socialism.

Oddly enough, while he is nearly forgotten in the U.S., today he is revered as a near-saint in Paraguay for his role in settling Paraguay's border dispute with Argentina over an uninhabitable outback known as the “Chaco.” Paraguayans celebrate an annual holiday in his honor, some calling him the “greatest man in Paraguayan history.”

Meanwhile, John Scott Harrison, who if alive would have celebrated his 201st birthday today, came nowhere near becoming president himself. He was, however, the only man cursed to be the son of one U.S. president (William Henry Harrison) and the father of another (Benjamin Harrison). Both his father and his son would have to be described as near nonentities on the stage of American history. John Scott Harrison briefly studied medicine (like his father), and served two terms as a Whig congressman from Ohio, but was defeated for reelection in 1856 as the Whig Party went into a state of mummification. He died in 1878 at his “Point Farm” in North Bend, Ohio, before his son had made a successful entry into politics.

Meanwhile, John Scott Harrison, who if alive would have celebrated his 201st birthday today, came nowhere near becoming president himself. He was, however, the only man cursed to be the son of one U.S. president (William Henry Harrison) and the father of another (Benjamin Harrison). Both his father and his son would have to be described as near nonentities on the stage of American history. John Scott Harrison briefly studied medicine (like his father), and served two terms as a Whig congressman from Ohio, but was defeated for reelection in 1856 as the Whig Party went into a state of mummification. He died in 1878 at his “Point Farm” in North Bend, Ohio, before his son had made a successful entry into politics.Harrison is perhaps best remembered for the peculiar circumstances of his burial. When Harrison was buried at his father's tomb near the family estate, it was noticed that a nearby grave had been robbed. Extra precautions were taken to make sure that Harrison's body would not be subject to a similarly rude disinterment, and his body was placed in a metal coffin encased in cemented marble slabs. During a search for the missing body from the nearby grave, authorities were startled to find John Scott Harrison's body, swinging upside down from a rope in a shaft in the Ohio Medical College in nearby Cincinnati -- stolen by Dr. Henri Le Caron just a few hours after his burial despite the extra security.

Ironically, Harrison's greatest personal impact on American public policy was that following the shameful grave-robbing incident, many state legislatures began to pass laws making it easier for medical schools to obtain cadavers for experimentation by legal means. John Scott Harrison may have been a political nobody, but given the track records of Ohio political notables over the years, perhaps Harrison’s legacy could be held as a standard for the aspirations of future Ohio politicians.

See also:

Chuck Todd, National Journal Hotline, "The Ghost of Teddy" (10/4/2005) on John McCain's "odd call" for Governor Taft's resignation

Labels: American Politicians

1 Comments:

If you can remember from almost five years ago, what are your sources on this article?

Thanks!

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home